Investigation: The spectacular rise and sudden fall of Gurpaal Judge

At the age of 24, a property agent in Wolverhampton had an awakening at a Buddhist retreat and decided to solve homelessness. This year, his companies collapsed owing £13m. What went wrong?

On the doorstep of his five-bedroom home in Wolverhampton, Gurpaal Judge is in a combative mood. “Oh mate, fuck off,” he tells me when I explain that I’m the journalist who has been trying to contact him online for the past few days. “You're going to write a story about us. You're not going to really understand the context.”

I tell him I want to hear his side of things. How did an inspiring non-profit company that garnered national newspaper coverage and eye-watering income in its mission to end homelessness end up going bust earlier this year owing millions of pounds? How had Judge, its charismatic young founder, ended up living in a house like this — with expensive cars dotted around the driveway — while vulnerable people who were housed by his companies are dying alone in miserable flats?

“It's nine months after the fact — just move on with it,” he says, looking as if he is going to close the door on me. But then, to my surprise, he doesn’t. For more than 20 minutes, Judge tries to explain himself, narrating a story that contradicts key aspects of the accounts given to The Dispatch by former senior staff members at his company and the evidence we have seen in public documents.

Did you get greedy along the way, I ask him? "No. The only thing we were greedy about was trying to house as many homeless people as possible."

The Buddhist retreat

Gurpaal Judge used to be a lettings agent. Property ran in the family — his dad was a buy-to-let landlord. But in 2018, when Judge was 24, an experience changed his life. At the end of a Buddhist retreat in Devon (“For five days he heard not a single human voice,” reported the Independent in a glowing profile two years ago), Judge switched on his phone and saw a message from someone at the local night shelter where Judge had been volunteering.

The message was about two homeless women at the shelter who badly needed housing. “When I woke up on day seven, the idea to do Lotus Sanctuary was in my head,” Judge told the Independent. “Within a month I’d quit my job and within another, we’d taken on our first two houses.”

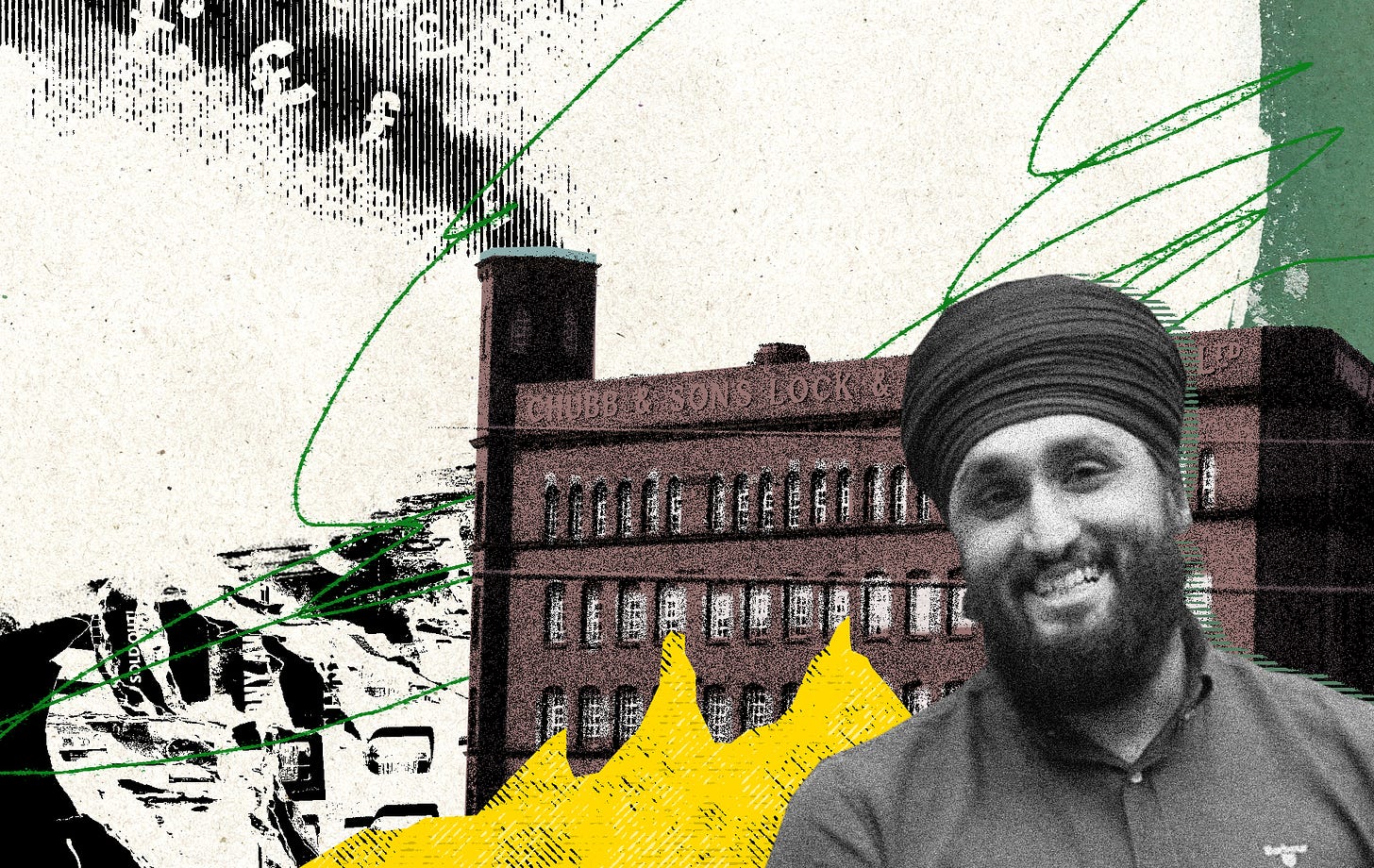

Soon after, he set up an organisation called Lotus Sanctuary CIC (meaning Community Interest Company) with its head office in Wolverhampton’s iconic Chubb building. Lotus Sanctuary said it had “the pure and simple intention of housing and empowering vulnerable women who are facing homelessness.”

According to former staff members at Lotus, the non-profit company would typically lease local properties in Wolverhampton and then use them to house vulnerable people who were eligible for supported housing. Lotus started out with two properties in 2018 and by all accounts, officials were happy with what was being provided. “These were visited and the residents interviewed, we were satisfied that the criteria was met and we had no concerns,” a spokesperson for City of Wolverhampton Council told me.

Judge says his mission was always to give people a decent place to live. “We pride ourselves on the quality of our housing, always keeping in mind that our residents are human and deserve to be given the best chance of overcoming the problems that lead them to needing accommodation,” he wrote in a submission to a parliamentary inquiry, emphasising the “ongoing support” that was offered to residents.

A growth machine

As of 30 June 2020, Lotus Sanctuary’s accounts at Companies House showed that after two years it was still a very small company. It employed an average of six people during the year (up from two in September 2019) and had total assets of less than £70,000 and just one director (Judge). At this point, Lotus Sanctuary was still a long way from solving the homelessness crisis.

By the time Judge signed off those accounts nine months later on 29 March 2021, things had changed dramatically. “Lotus blossoms”, said a March 2021 headline on The Business Desk, “as it leverages £30 million of investment to tackle homelessness for women”. Lotus Sanctuary was now offering up to 550 bed-spaces for vulnerable women, up from 24 beds a year earlier. These consisted of “1-, 2- and 3-bed properties across the East and West Midlands, the North West, the North East, the South West and Yorkshire and Humber.”

The numbers kept growing. As of August 2022 Lotus Sanctuary CIC and its sister organisation Redemption Project CIC — also set up by Judge — said they could provide housing and high quality support for at least 1,800 vulnerable individuals.

What was going on here? How was a man in his late twenties with no business experience able to chalk up such vast numbers? After all, neither Judge nor his company had any meaningful cash of their own. To answer that, you need to understand a murky world that we have been investigating for several months now — a world of 25-year “government guaranteed” leases, stock market-listed housing funds and the booming market for “exempt accommodation”.

Here’s the background: For certain groups of working-age people, the government funds higher-than-average rent payments which are “exempt” from the usual caps on housing benefit. This higher rent is supposed to pay for the extra support that vulnerable individuals such as victims of domestic violence need to receive for a period before they can return to independent living.

As explained by the website Inside Housing: “In Birmingham, the maximum amount of housing benefit that can be awarded for someone living in a shared room in a traditional house of multiple occupancy (HMO) is just over £291 a month. In exempt accommodation, it is over £850. An extra £60 in service charge can also be taken.”

The Birmingham example isn’t plucked out of thin air. Some readers will be familiar with the concept of “exempt accommodation”, or EA, because Birmingham has become notorious for this type of housing, with numbers rising to 21,000 claimants. The story of Lotus and its founder Judge offers a rare window into how this industry has developed and operated.

Crucially, the government rent is paid not to the individual but to the organisations that provide housing and support. In order to qualify, such an organisation must be (broadly) non-profit. Registered charities would be the most obvious example, but not the only one. This rule seems to have created some perverse incentives — and a new breed of non-profit housing provider of the sort founded by Judge.

What was driving this trend? Using some imaginary numbers, we can see how exempt housing benefit can be used to inflate the value of homes. Suppose you pay £100,000 for a flat that you can rent out for £100/week — the annual yield on your investment will be just over five per cent. But then you discover you can rent the flat instead to a charity that will be able to pay much higher rent, because it’s housing victims of domestic violence.

Now imagine the charity is also willing to sign a 20- or 25-year lease that obliges it to pay this same higher rent for the next 25 years, adjusted upwards for inflation. Locking in that higher rent for 25 years means property investors will now pay a premium for your flat. Simply by attaching that 25-year lease to your flat, you’ve just made a quick profit.

The trouble is, well-run organisations don’t typically sign up to this kind of lease. That’s because they know they would be writing a financial suicide note. In order to cover its own lease payments, the charity has to be sure it will receive the higher government rental income for 20-25 years. That’s a long way into the future — especially with no contract extending anything like that far. If the government payments ever stop, the charity won’t be able to make its own lease payments. Then it will go bust.

This is where organisations like Lotus Sanctuary came in. Their founders, like Gurpaal Judge, had no cash or track record, but were so fixated on growth that they would sign up to these leases. Every time they signed a big lease, the investors who owned the buildings would pay them a big upfront “capitalisation” payment to cover the costs of furnishing and setting up flats for vulnerable people. In some cases, that payment would represent 12 months of rent.

All of this explains why after June 2020, Lotus Sanctuary started to grow like Topsy. Judge’s organisation was signing new leases to take over buildings and house vulnerable people at a dizzying rate. The way Lotus Sanctuary’s growth forecast inflated would be laughable if this wasn’t so serious: 24 beds in early 2020; 2,000 beds by December 2021; 5,000 by 2022; 10,000 by 2023.

Two organisations that Judge had founded were renting some of their bed spaces from the same big landlord, a stock market-listed fund called Home REIT. One was Lotus Sanctuary and the other was a similar outfit called Redemption Project CIC that Judge set up in November 2020. By August 2022 the two were renting 1,829 bed spaces between them, split about evenly.

Such rapid growth meant Lotus Sanctuary had to do a lot of hiring. Between June 2020 and March 2022, its workforce expanded from six employees to 88. “People were giving up jobs in respectable places,” one former staff member recalls. What was the appeal of joining Lotus? They say Judge had a certain charisma about him, but the big thing was his soaring ambition. “He was saying we are going to end homelessness.”

In March 2021 Lotus was talking about “over £30 million of private sector investment”. Four months later the figure had grown to £250 million. The company explained to the Wolverhampton Express & Star why investors should be interested: “In essence, we are the safest investment they can make with 20-year leases on their properties giving them a guaranteed income…”

‘Absolute toilets’

As it turns out, the incomes were certainly not guaranteed. And more importantly, neither was the “ongoing support” that Judge said was so central to his philosophy — and which justified the higher-than-market rents paid for exempt accommodation.

According to former senior staff members we have spoken to, the rosy headlines about Lotus stood in stark contrast to the chaos and dysfunction taking place behind the scenes. Starting a couple of years ago, the company began taking on new buildings at an unsustainable speed.

“We would go to meetings and they [the company’s management] would say we have another 200-bed unit, and we would say we don't have enough staff to offer the support,” says one person who held a senior role organising support for residents. She recalls that around the start of 2022, “these properties kept being brought on even though the existing ones were a mess and had no staff and had constant issues.”

“We were taking on absolute toilets,” says another staff member who worked in the finance side of the company. “Really bad properties.” Staff recall “lots of places with rats”, cupboards falling on residents’ heads and a property that had six feet of water in the cellar for “a very long time.”

At times, Judge’s expansive approach to property acquisition verged on the comic, like when the company took on a former convent near Rugby with 12 acres of land attached. “What are we going to do with that?” one staffer recalls thinking. “What the fuck are we going to do with a nun's farm?” What did she make of the company’s approach to taking on new properties? “They essentially took on places anywhere because it made them money,” she says. “They took on literally anywhere.”

One of the big issues for Lotus was that support workers were quitting all the time. “We were paying the same as McDonald’s and expecting people to go and support people in these houses that were not fit for purpose,” the former staffer recalls. “It was rare there wasn't a resignation to deal with in our Monday meetings.”

The staff member who worked in the support side of the company remembers the same problem. “Staff would literally leave daily — they would quit on the spot when they realised how bad it was,” she told The Dispatch. “They had people joining with no office to go to and no induction. You would just be sent to a building and asked to support people.”

It may have been a bad deal for staff, but it was even worse for the vulnerable residents, including homeless people, women who had suffered domestic abuse, and recently released prisoners. “Anyone who was in those properties was a loser,” says a former Lotus staffer. “They weren't getting the support because we couldn't get the staff.”

In April 2022 the government’s Domestic Abuse Commissioner named and shamed Lotus Sanctuary facilities in Sunderland and Yorkshire. Here’s one example: “Lotus Sanctuary stated that the support they provide to survivors of domestic abuse housed in their accommodation in Kirklees is limited to one hour per week, but that the women ‘can ring if they need anything’.”

When I put the allegation about a lack of support to Judge, he vehemently denied it. “We were giving the support,” he said. “We wouldn't move a homeless person into a home unless a support worker was already attached to that home. One of the key issues we had was recruiting support workers, but we were never over the capacity of one support worker to 15 residents.”

Where did the pressure to expand so fast come from? Judge says it was the urgency of the country’s homelessness crisis. “When you are in a situation where all you want to do is house homeless people and you are given the opportunity to do so, you are going to do so at high speed,” he told me. “You are going to take on as many houses as possible.”

But oddly, some of the local councils don’t seem to have welcomed Judge with open arms. In fact, the former employees we’ve spoken to suggest that Judge’s model was to take on leases before properly consulting with councils. “He didn’t engage with local authorities before opening these projects,” says one source, who remembers awkward meetings with council officers, in which Lotus staff “had to blag” their way into getting approvals.

“These buildings would never be appropriate — the councils would say ‘we don't want big blocks of homeless people living together’,” says the former staff member. How would these conflicts be resolved? “His argument was that he [Judge] would sue them if they didn't pay,” a different ex-employee recalls. “He was moving so quickly, he had so many properties coming in.”

Whatever Judge’s tactics were, they didn’t seem to work. Publicly, he was citing very large numbers — the thousands of properties on which his companies had leases. But astonishingly, it turns out that most of these properties were not in fact housing vulnerable people. “Of the 2,500 beds they had, less than 300 were supported accommodation,” one former staffer recalls. The rest were either empty or had private rental tenants who were still in there from when the property had been taken over.

That fact — which Judge admits to, although he says “at least 450” exempt tenants at any one time — might help to answer the question of why Lotus had to keep on taking new buildings. Namely, if it wasn’t receiving the anticipated exempt accommodation rents for most of its units, the company needed to take on more and more new properties in order to receive the up-front “capitalisation” payments from the private landlords. According to insiders, those payments — which sometimes counted in the millions — were what was keeping the show on the road.

“It was always going to end,” says one former staff member. “It was propped up by new people coming in.”

A major payout

On his first day at Lotus, one employee remembers seeing a white Mercedes belonging to Judge sitting outside in the car park of the Chubb building with a personalised number plate that read: L8TUS. That created a strange first impression, they recall. “You are working with the most vulnerable people in the UK and you are going around in a souped-up Merc with a personalised number plate,” they told The Dispatch. “It doesn't suggest you are in it for the right reasons.”

While Lotus talked publicly about its “pure and simple intention”, Judge’s actions suggest he also had an active interest in his net worth. The last set of accounts that Lotus filed at Companies House disclosed that its directors were paid £135,538 for the 12 months ending 31 March 2022. Lotus had only two directors during that period: Gurpaal Judge for the full year, and a Lotus employee for about four and a half months.

This suggests Judge was paid at least £100,000 in the year ending March 2022. For context, take a long-established and national-scale homeless charity based in London whose annual income of £65 million and 735 employees both dwarf Lotus Sanctuary. In 2021 this organisation’s CEO was paid somewhere between £110,000 and £120,000.

Then, in March this year, the newspaper CityAM reported that a confidential bankruptcy document showed that in the year just before Lotus Sanctuary went bust, its directors (including Judge) had been paid £1.2 million. Judge has not denied receiving that payment.

What about the lovely house where we met Judge last week? Not many houses up for sale in Wolverhampton get their own marketing video, but in 2021 a local estate agent decided that this ostentatious detached five-bedroom property was worth it. Land Registry records show that in September 2021, Gurpaal Judge and his then-partner bought this house together for £640,000.

Starting in November 2021, both Judge and his co-owner made this property the registered address for several companies they owned (not including Lotus Sanctuary). Judge used two companies that he registered at this address to buy further property investments located in Accrington, Lancashire and Middlesbrough.

These were very different from the five-bedroom establishment in Wolverhampton. A house in Accrington for which one of Judge’s companies likely paid £100,000 is just the kind of modest three-bed terrace that crops up all around the country in relation to exempt accommodation. Home REIT and other big landlords, as well as individuals, were buying hundreds of these properties in order to rent them for 25 years to organisations like Lotus.

Judge’s house in Accrington involved an unusual extra wrinkle. Lotus Sanctuary’s founder was renting this house (which he owned) to Lotus Sanctuary (the non-profit organisation that he ran). That creates a potential conflict of interest and a well-run organisation would take steps to ensure that Lotus Sanctuary wasn’t giving favourable insider terms to its CEO. Given that Judge was both Lotus Sanctuary’s CEO and (most of the time) its sole director, it seems reasonable to wonder if Lotus Sanctuary took any such steps. When we asked Judge about this in writing via messages on LinkedIn, he chose not to respond and deactivated his account.

The Accrington house also involves another bizarre feature. Companies House filings show that the Judge-controlled company which owned this property had rented it simultaneously to Lotus Sanctuary CIC and to Judge’s other main organisation, Redemption Project CIC. Perhaps each organisation was only renting some of the rooms in that modest terraced house in Accrington.

Judge was not the only senior Lotus Sanctuary insider who was renting properties that they owned to the organisation they worked for. At least two other senior employees who worked for both Lotus Sanctuary and Redemption Project did the same. One of them, too, was renting a property simultaneously to both organisations.

When we asked Judge about his personal wealth and the cars — including a BMW and a Mercedes — sitting in his driveway, he said he has been working since the age of 16 and that he has earned money from other projects too. “I have done well out of a multitude of things,” he said. “I haven't had just one company.”

A death in Worcester

In January this year, just after 10am on 23 January, Gurpaal Judge wrote a short email to all of his staff. “I know there has been some murmurings,” he wrote, admitting that over the past few months “we have found it increasingly difficult to get sign off on exempt status from local authorities”. He said the company was owed more than £2.7 million by various councils, which was causing “short term cash flow issues”.

All staff would be paid as normal, he wrote, but his tone wasn’t particularly reassuring. “It’s too early to say the direction of travel in the longer term,” he told his team, asking them to carry on operating as usual.

Just over a month later, on 6 March, Lotus Sanctuary officially went bust. A document it filed at Companies House showed debts of over £7 million, with less than £1 million in assets. Five months later, Redemption Project CIC, the Lotus-like organisation founded by Judge, also went bust with a similar deficit. In total, his companies collapsed owing just over £13m.

To date, Lotus Sanctuary’s liquidator Begbies Traynor has officially torn up leases that Lotus Sanctuary had signed on more than 120 properties. Those landlords are now out of pocket and many more are likely to follow. Even in failure, though, Judge remains larger than life. Lotus Sanctuary’s demise is apparently too big for Begbies Traynor’s local Wolverhampton office to handle: a note on its website redirects enquiries about Lotus Sanctuary to a London phone number.

When The Dispatch contacted Begbies, one of the insolvency lawyers working on the case said it wouldn’t be appropriate to comment at this time.

Judge puts the collapse of his companies down to councils refusing to pay the money they owed, and he is adamant on this point, repeating it five or six times during our 20-minute conversation. “We tried to help people,” he told us. “The local authorities owed us millions of pounds — £4.1m — in backdated rents.”

He says our reporting is based on "anecdotal stories" from "disgruntled staff members" and that if we spoke to others involved in the company, we would get a much rosier picture. When we asked him to pass on contacts for such people, he said it would be a waste of time.

How does one of those supposedly disgruntled former staff members reflect on what they experienced? “A joke. Just absolute madness,” they told me. “I can't believe that no one has been held accountable for it. These people got away with it, and they are going to be able to run companies again.”

What are we supposed to conclude about Judge’s motives in all of this? The people I’ve spoken to for this story seem to broadly agree that he probably started out with a certain amount of idealism about tackling homelessness. “I think he was genuinely helping people, and then the money went to his head,” says one person who knew him personally. “So he was trying to do both.”

“I want to see the good in everyone,” says a former Lotus executive. “When he set up Lotus, he didn't know about Home REIT and he didn't do any long leases. They were typically shorter leases like five years to people he knew in and around Wolverhampton. Then something happened along the way and he grew quicker and then fundamentally too quick. I think he saw a way to make a lot of money very quickly.”

On a broader level, what was going on inside Judge’s head doesn’t particularly matter. What matters is that the broken system of supported housing allowed him to take responsibility for so many people’s lives. This kind of failure is what happens in the vacuum where publicly funded services used to be — where the state has stepped away from its duties to look after the most vulnerable people in society in the hope that unproven private providers — backed by hard-nosed investors — will be able to do things on the cheap.

Judge strongly refutes the suggestions that he was greedy or that he was operating in a broken system in which private investors and brand new non-profit companies with very limited track records are making large sums of money out of housing vulnerable people. And he says he is devastated by the collapse of his housing empire. “You don't think I'm heartbroken for the hundreds and thousands of people that we helped and we could have helped more?” he asks near the end of our conversation.

A spokesperson for City of Wolverhampton Council tells The Dispatch that concerns about Lotus accommodation in Yorkshire were first reported to them in September 2021. “At around the same time we received allegations about poor standards of accommodation and a lack of support in Wolverhampton,” they said. “We began a series of inspections to the properties in Wolverhampton. This led us to terminate the claims for Housing Benefit because it is only payable if support is being provided.”

For some reason, no one in the council seems to have informed the city’s mayor, councillor Greg Brackenridge, who stood alongside Judge to open a Lotus Living Hub in Bilston in March last year. Would the council work with Judge again? The spokesperson told us: “If companies linked to Mr Judge were to operate in Wolverhampton again, we would put extensive measures in place to ensure standards were being maintained.”

Aside from Judge, who were the winners from this saga? Almost certainly the property dealers. Their profits came from selling properties at artificial values supported by leases signed by organisations like Lotus Sanctuary and Redemption Project. On the other side of the deal, there were investors and landlords — including the massive stock market fund Home REIT — who paid too much for properties.

Home REIT collapsed spectacularly earlier this year, following a report published in 2022 by a short-seller that called the business model into question. One of the examples cited in the short-seller’s report was one of Home REIT’s biggest tenants: Lotus Sanctuary.

But of course, the biggest losers are the people who were living in Judge’s properties, including some of the most vulnerable people in society. It is assumed that most of these properties have now been moved over to new providers, although former Lotus staff we have spoken to fear that this process won’t have gone smoothly. At times, organisation inside the company was so poor — and support staff were leaving so often — that Lotus didn’t know who was living in certain properties. “I reckon there will still be people in there now, just blissfully unaware Lotus has gone bust,” says the company’s former head of support services. “And no one has done anything.”

In early April, a month after Lotus collapsed, residents in one of its buildings in Worcester became concerned about one of their neighbours because they hadn’t heard from her. Eventually, they broke in through the woman’s window and found her — she had choked on her own sick and had been dead for five days.

A former staff member at Lotus recalls that story with a sense of horror. “They had all these vulnerable people in the properties and any support they had just stopped,” she said. A spokesperson for Worcester City Council confirmed that the incident took place, but did not want to comment.

Judge also heard about the woman’s death. In tone, he is still combative — still unshaken in his version of the truth. “Had the insolvency not happened, guess what — she would be alive because she would have support,” he says, standing on his doorstep. “She would be. You don't think that hurts me — that someone died in our property? You don't think that fucking hurts?”

Read Part 2 of our investigation, which looks at the conditions vulnerable people lived in, and where we visit a few of the properties concerned.

Join our free mailing list to get high-quality local journalism from the West Midlands in your inbox every day. Hit the button below.

If you believe in this kind of investigative journalism and you want us to be able to do more of it, please pledge to become a paying Dispatch member by logging into our site and hitting the green button. Please get in touch if you have more information about this story — we are planning more coverage of this area in future.

Very interesting article, clearly well researched. I'm still pondering his motives. Removing public sector provision in favour of private always bound to lead here

Thanks for this detailed bit of investigative journalism!

I've been of the opinion for some time that these Exempt Accommodation schemes are ripe for abuse by unscrupulous people as a way to rinse local authorities and make huge sums of money, while providing little in the way of support.

It also has a knock-on effect in the housing market, especially for renters, as greedy landlords and companies snap-up properties, knowing they can rent them to councils above the going-rate. Which means there are fewer rental properties available for private individuals, which in turn then drives up rental rates.