When the author Kasim Ali was growing up in Alum Rock in the late 1990s, he lived across the street from a family that was almost the mirror image of his. There was a boy his age, who was also called Kasim. His mother had the same name as Ali’s mom.

“One time, when I was very young, my mom didn't let me out of the house one weekend, because Kasim from across the road was involved in a gang,” Ali says. “She was worried they might see me and hear someone call my name and think that I was him, and they may do something to me.”

The sense of danger was terrifying, Ali tells me, but also exhilarating.

It was a sliding doors-esque moment — the young Ali was brushing up against a potential future. Joining a gang and selling drugs was a very different path to the one he ended up choosing — leaving Birmingham to study at the University of Derby, then moving to London to work in publishing — but the option was there. He could have taken it.

“I spent a lot of my childhood watching young men my age have lots of money, or wanting to have that money, but also being terrified of the violence that came with that money,” Ali tells me.

It’s the same predicament faced by Amir, the 20-year-old protagonist of Ali’s new novel, Who Will Remain — indeed, Ali dedicates the book “to the man I could have been if I wasn’t such a coward”. Amir is a smart, slightly chubby, young British Pakistani man with a chip on his shoulder. It’s the final leg of a difficult second year in his Civil Engineering degree at a local university, and he is living at home with his parents in Alum Rock. His dad is giving him a hard time, his mom is worried that he is staying out too late with his friends, and he’s sick of not having any money.

The novel opens with the funeral of Amir’s close cousin Saqib, lost to a stab wound in a gang fight. Shortly afterwards, Amir’s other pillar, his older brother Bilal, announces that he and his secret girlfriend are engaged. We learn that Amir’s own secret girlfriend ended their relationship nine months ago, and he’s deeply sad about it. When an old friend reappears in his life, much wealthier than before and willing to let Amir in on his lucrative drug dealing business, the opportunity is difficult to resist.

While different in many ways, Who Will Remain is a coming of age story that bears the hallmarks of modern classics like J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and Sylvia Plath’s, The Bell Jar. Like the central characters in those novels, Amir is dealing with the onset of psychological distress just as he is approaching the cliff face of adulthood; his crossroads resembles Plath’s fig tree (in her 1963 novel, the depressed heroine imagines her potential futures as figs, wilting on their boughs while she delays picking one) an image that has found new resonance with younger generations on social media today.

Where the situation differs from The Bell Jar are the limitations Amir faces due to his identity: as a British-Pakistani man, a Muslim, and a resident of Alum Rock — an “Alum Rockie” as his wealthy university friend calls him.

Alum Rock’s violence is on the periphery of Amir’s existence, but until he faces certain pressures, he isn’t tempted by gang life, nor is he particularly close to it. His mom doesn't work, his dad is a taxi driver and his brother, who went to university in Durham, works in tech. His friends are mostly other young men who go to the same university as him and spend their time playing video games, going to the gym and smoking weed.

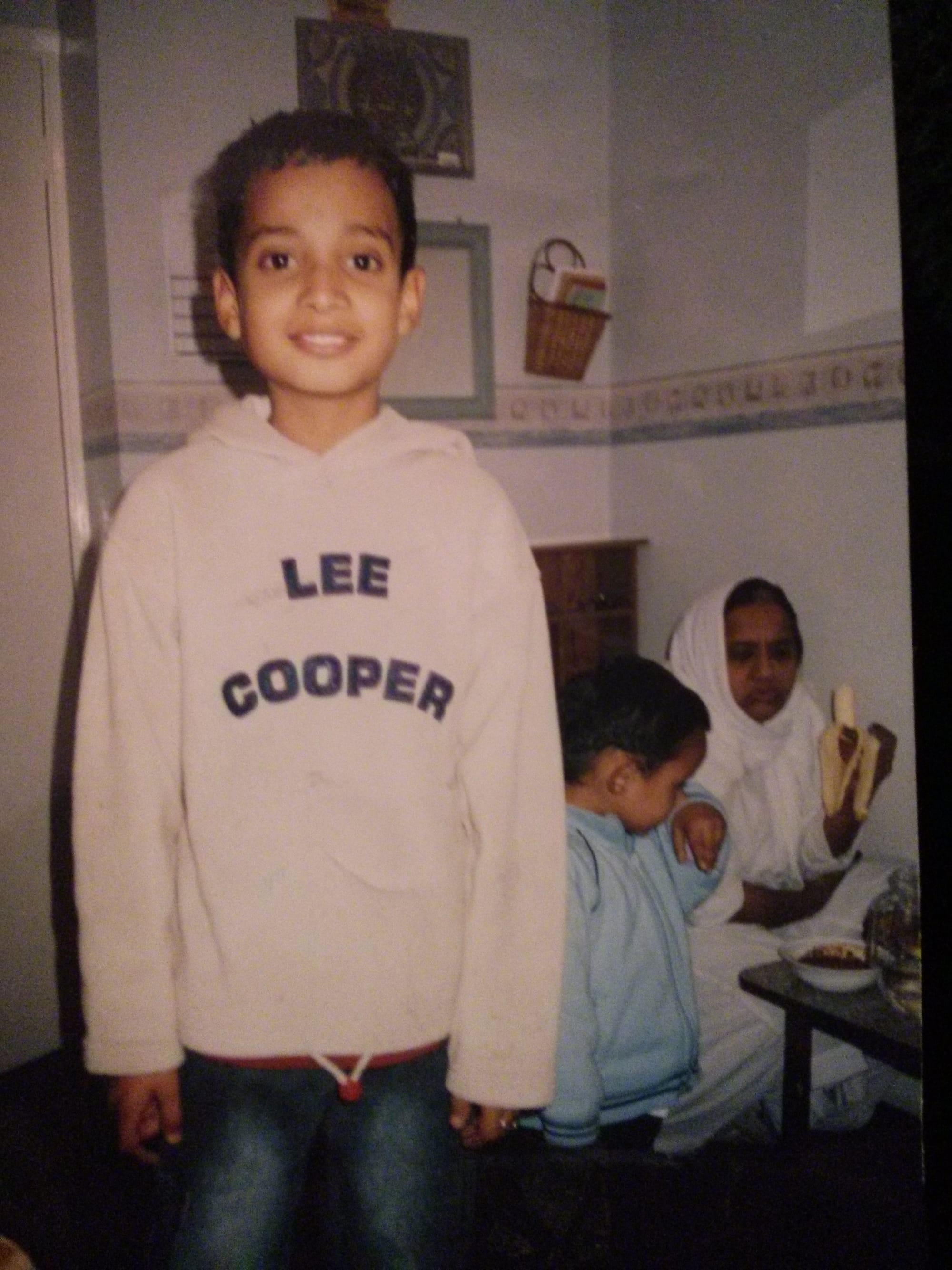

As for Ali, he says that for the first 16 years of his life, he didn’t know that Alum Rock bore such a stigma. His maternal grandparents arrived in Alum Rock from Pakistan in the 1960s and raised their five children here. His dad came over in the 1990s, after marrying his mom. Almost all of Ali’s family, including him and his three siblings, were born in Heartlands Hospital.

His primary school, secondary school and mosque were all a five minute walk from his home. His parents liked to stay in and besides, they didn’t have the money for holidays. “There was never any need to leave Alum Rock,” he tells me.

It was when he turned 16 and began making the daily, two mile trek into town for sixth form college that he realised something was up. “That was the first time I came into contact with people who weren’t from Alum Rock,” he says. “I was like, ‘oh my god, Alum Rock has a really bad reputation! And yet I live there.’”

Later, after university, a job at Curry’s in town brought this into sharper focus when a workmate bluntly told him, “I can’t believe Alum Rock created someone like you.” They meant it as a compliment. “I was like, ‘what are you talking about?’ There are so many of us like this,” Ali says. “There are doctors, lawyers and teachers. My auntie is a cancer researcher, my other auntie has had a 30 year career in the NHS. It really frustrated me.”

But the stigma is real — all the more so in the years since the Trojan Horse affair unfolded, a scandal where the Conservative government at the time enacted a controversial national policy based on false claims that Muslim educators had cooked up an “Islamist plot” to take over local schools. Ali’s secondary school, Park View (now called Rockwood Academy) was at the centre of the allegations.

Although Park View is only briefly mentioned in Who Will Remain, an earlier draft dealt directly with the maelstrom it was part of. In that version, Amir’s uncle talks about how the Trojan Horse affair affected the community, but that even in the face of this hostility, Amir has the opportunity to live a successful and safe life because he is smart. However: “I just couldn't make it work,” says Ali. “It just felt too preachy, too monologue-y.”

The author — who is also a commissioning editor at Bonnier Books UK — attended Park View between 2005 and 2010, just before the conspiracy broke. He says “the school that I started reading about was not the school that I went to.” While there, he grew close with a teacher called Razwan Faraz who “could immediately see that I really like to write and so he pushed me quite a bit to read more widely.” According to Ali, Faraz told him, “don't let people tell you that someone like you can't be a writer.”

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Faraz, in his later role as deputy head of Nansen primary school, was one of five senior teachers to be charged with professional misconduct related to the Trojan Horse inquiry. The charges were dropped but he was dismissed from his job for making homophobic comments in a private WhatsApp group. “Don't get me wrong,” says Ali, “from transcripts of WhatsApp messages I've seen, he said some really despicable things about queer people in particular that don't sit right with me.” But he also “pushed me in a way that no one else really did at [Park View], so you have to weigh those things up.”

The question of what to do with his life hung heavy for the young Ali; the same is true of his cast in Who Will Remain, who discuss their futures with the same worry and doubt that most on the threshold of adulthood do. But their status as British Muslims from an economically deprived area of Birmingham adds extra complications. The question of what is possible is always in the air; they say things like “that future isn’t meant for people like us”.

Farrah, Amir’s fleeting love interest, has a doctor father and a politician mother and she studies hard at the red brick University of Birmingham. And yet, that isn’t enough; she wants to be a filmmaker but knows it will require her to move to London and slog it out from the bottom up. Passion alone, and even her middle-class background won’t ensure her success.

“It should be enough that I love it so much,” Farrah complains at one point. “That’s the way it is for other people, they decide they want to be a director or a writer or a producer and their parents know all of these powerful people who give them a job, get them into the room”. But she and Amir are “on the outside,” she says. “Banging on the door, trying to get in, and it’s exhausting”.

Her appearance in the narrative brings hope — smart, funny and principled, she represents another crossroads for Amir, a positive influence. That’s if his other distractions won’t stop getting in the way. At times, you want to shake our hero.

“I like that it’s sort of complicated,” says Ali. “You kind of want to be on [his] side, but then you're also [thinking] I wish you wouldn’t do these things and I wish you would stop that,” says Ali. One scene in particular stands out as an example; without spoilers, it’s a sex scene where consent is ambiguous at best. Ali found it “incredibly difficult” to write, he confides.

“First, my worry was, is somebody going to read this book and think that I am saying all Pakistani men are like this?” he tells me. As someone who works in publishing, he understands that the burden of representing his community often falls to writers like him. He struggled with how to realistically portray flawed, human characters without giving fodder to those who would scapegoat entire demographics. This tension is obvious in the epigraph Ali chose to open the book: a 2023 quote from former home secretary, Suella Braverman: “British-Pakistani males (...) hold cultural values totally at odds with British values.”

In the end though, after dwelling on the fact that he can’t write for everybody, Ali decided he had to “ultimately just let that go” to tell the tale he wanted to tell — a nuanced coming of age story about a conflicted young man. Many of the problems its protagonist faces are universal to the experience of growing up. Some of them are specific to life in Alum Rock.

Comments