Dear readers, Kate here. The story you're about to read is the kind of thing I love to write. It's got drama, it's got romance. It's got twists and turns. It also took a fair bit of work. I spent about six hours on the phone to sources, plus several more factchecking and proofreading. I had to hunt down an old torn poster someone had held onto since 1983, just to prove someone else was telling a porky (or had misremembered certain information, if we're being generous). This is the kind of local journalism the big companies don't bother with - they simply don't think Birmingham needs it. But I disagree. And if you're reading this, perhaps you do too. The Dispatch is aiming to get 200 new paying members by the end of October - and we're so close. Help us, and support independent media, by signing up to The Dispatch today.

Sunset Boulevard, Wednesday 30 September, 1981. A quartet of skinny youths – two men, two women – have just spilled off the stage at legendary music venue, Whiskey A Go Go, and into a backstage dressing room. Outside, a hungry crowd clamours for more. The long journey from Birmingham has been worth it for Au Pairs; their brand of frantic post-punk has gone down a storm with The Whisky’s patrons. Now, exhaustion mingles with adrenaline as they take stock of their reception.

In strides The Whisky’s manager, a paragon of all-American enthusiasm: “Yeah! Great show guys, next one in about 45 minutes.”

The band members stop dabbing the sweat from their faces, look round at each other and burst out laughing. As usual, they’d left everything they had on that stage; there was no way they were going to do that again. As the manager rages, they slip out together, unfazed, into the balmy LA night.

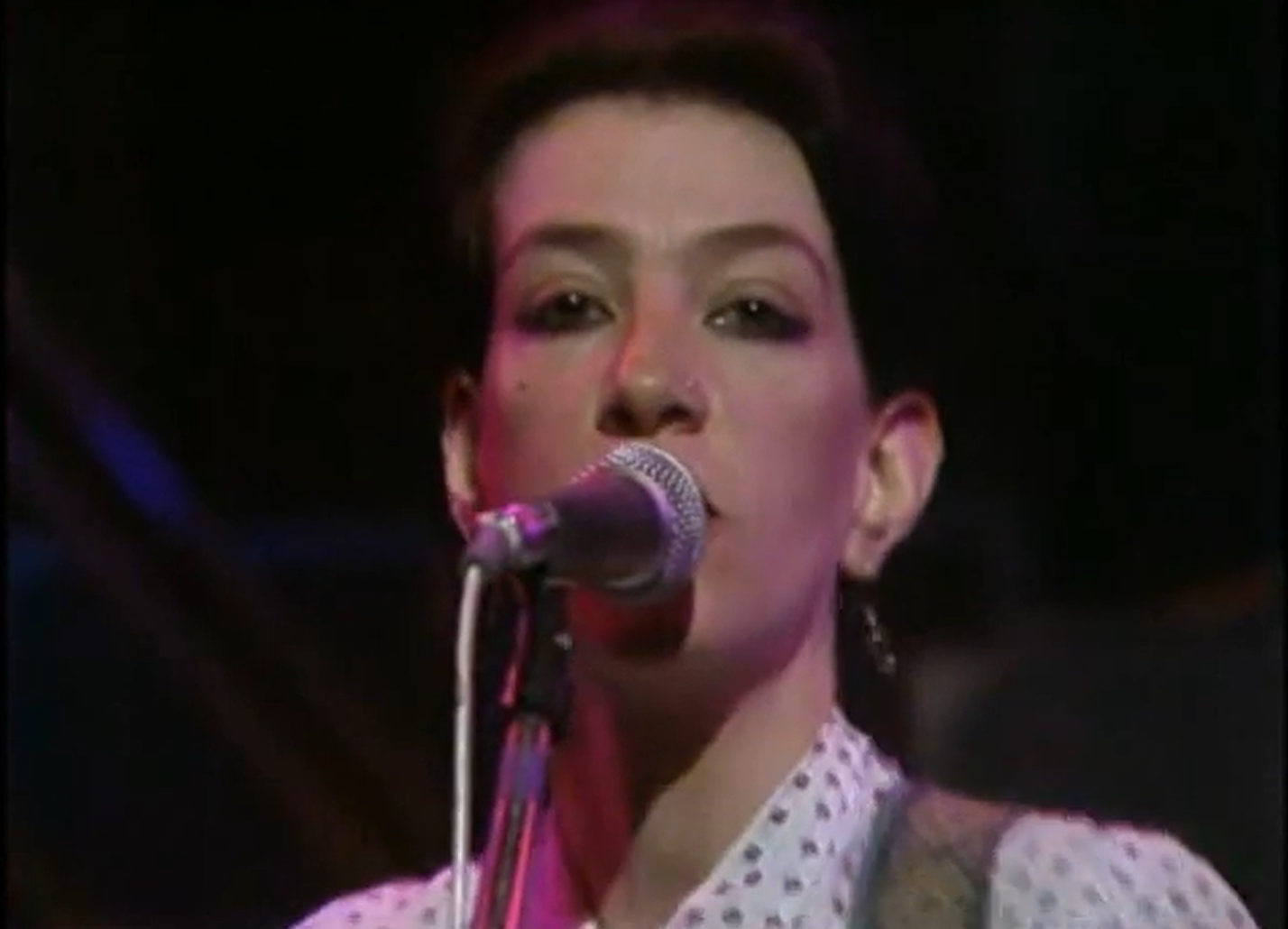

At the height of their powers, Au Pairs were a united front. Formed three years before the LA gig, they honed a sound that melded the ferocity of punk with smart lyrics that challenged established norms around sex and gender. Their first of two albums, Playing with a Different Sex, set the tone for a small but mighty repertoire. Lasting mainstream recognition proved elusive but that’s how Au Pairs liked it; for those in the know, the band is considered to have been at the vanguard of post-punk. They certainly found a fan in Kurt Cobain – he loved them.

Between 1978 and 1982, Paul Foad played guitar, Jane Munro (now Dowsett) was on bass, Peter Hammond took the drums and Lesley Woods — described as “one of the most striking women in British rock” — was frontwoman. The two guys were old friends from school; Woods and Foad were lovers who had met at a bus stop, and Dowsett joined last, slipping easily into the group that was balanced both in gender and shares. They signed an agreement that all credits and money would be split equally.

Forty-two years after Au Pairs parted ways, promoters AGMP announced in July a 2026 reunion “for their first concert in 40+ years”. This was news to three of the band’s original members who were astonished to learn they would supposedly be back on stage the following year.

Foad, Dowsett and Hammond had no clue about any reconciliation. It soon became clear they weren’t included in the plans: the Au Pairs ‘reunion’ would feature Lesley Woods, alongside three new band members. What’s more, Woods had quietly trademarked the band’s name, without the trio’s knowledge.

What followed has been a fierce — and very public — war of words and allegations between the former bandmates, exposing a bitter rift that has been brewing privately for decades. “There is no way we could have reunited with Lesley after so many years of disagreements, unpleasantness and deceit,” Foad, Dowsett and Hammond declared in a joint statement last month.

“This whole pantomime is in three parts,” Hammond tells me. “I think it’s worth going back to the beginning.”

The early days

It was the leather jacket that did it. That’s what 18-year-old Paul Foad was wearing when Lesley Woods first clocked him. He was standing at a bus stop on the Pershore Road in Stirchley. It was 1976, he had long, black curly hair, and he told her he played guitar. “I thought, ‘oh, great, this guy's really good looking; he is really cool,’” Woods says today, over the phone, in a throaty Essex drawl. “I fancied him. And I also wanted to play music.”

Foad, who still sports his broad Brummie accent, recalls: “Because I had a leather jacket on and a guitar with me, she just started talking to me.” Woods was an 18-year-old student; her digs were just down the road from where Foad lived with his parents. Shortly after their chance meeting, she paid him a visit. “She just came up, knocked on the door one day and asked for some guitar lessons,” he says. And that was that.

Woods does not recall the guitar lessons, but she fell in love all the same. Meanwhile, Peter Hammond, who is originally from Northfield, was rattling around Europe in a battered old Volkswagen van. He was a music obsessive, a drummer, and every chance he got he’d stop to root through record shops, listening to all the new tunes he could get his hands on.

“I was completely up to date with all the punk stuff,” he says, keen to emphasise his credentials. “Post-punk, everything.” A year later, he returned to Birmingham and reunited with his old school friend Foad, who was now living with Woods in Smethwick. The couple were playing folk music together; Foad asked Hammond if he was interested in forming a band. But Hammond knew folk wasn’t going to cut it. For the past 12 months he’d been immersed in bands like The Cramps, X-Ray Spex and The Slits — that was the direction he thought they should go in.

“From there grew this seed of an idea,” Hammond says. They wanted a fourth member, a woman, and were introduced to Jane Dowsett who had recently started playing bass. One day, Foad picked her up from Moseley in his little van and took her to the Earl Grey pub in Balsall Heath. In a large function room upstairs that smelt of stale beer and fags, the foursome came together for their first rehearsal.

“I was quite overwhelmed because it was all so new to me,” Dowsett tells me. “But Paul in particular, was incredible and he taught me a lot. Right after the first rehearsal, he said that I was a natural. I don't know how true that was really but he was always very encouraging.”

It was 1978. The winter of discontent was afoot and Margaret Thatcher was on the rise, as the far-right and anti-fascists clashed in the streets. The tail end of a cultural rebellion was taking place, influenced by second-wave feminism and struggles for equal rights; artists were rejecting the money-soaked big business of the music industry, opting instead for DIY methods and the freedom to express their political views without censorship. The Au Pairs wanted in.

“The idea of having two men and two women, all of whom were equals, and then to share all the songwriting credits,” says Jane, “all sort of sat well together, and that was what we decided to do.”

“The ethos was all of us, we do it all together,” adds Hammond. “Nobody did any one thing that was more important than the others.”

The Earl Grey session was the start of something special. The band acquired their name shortly after, but it took at least a year of constant gigging before they got a break, playing endless charity shows like Rock Against Racism, as well as regular paying gigs. The Au Pairs pooled every penny; in 1979 they finally had enough money to release their own single and print 1,000 records.

“We had a big, 24-hour party when everyone in Moseley came round to glue all the covers together and put the records in,” says Hammond. They sent a copy to John Peel who played it on BBC Radio 1 and invited them on. A record deal soon followed and Playing for a Different Sex was released in 1981. A New York Times review from the time described Lesley as “the Au Pairs' principal lyricist and vocalist”, and praised the group’s “springy, funk-influenced dance rhythms and deftly interlocked guitar parts”.

Over the next five years the foursome lived in each other’s pockets, experiencing the highs and lows of being a band on the up. They played New York with the band Gang of Four on New Year’s Eve, arriving into the city in the back of a limo, guitar cases piled on top of them. They were banned from the BBC after flouting the rules by playing ‘Armagh’, their song about The Troubles, live on national television.

Throughout it all, according to Hammond, they were fiercely committed to the collective project. “We did every single mile on the motorway together, we suffered all the ups and downs,” he says. “We got ripped off financially together — the whole thing. We became the poster band for that kind of political agenda.” He doesn’t remember things getting weird, or competitive or bitter. Neither does Dowsett or Foad. “Whatever people say about it now, we had a brilliant time,” Foad tells me “Nothing but great memories.”

Woods agrees — to a degree. “It's like every band or every relationship at the beginning, it's always pretty euphoric; it's passionate, it's fun,” she says. “I think towards the end, it did start to change. But that's for complicated reasons that are extremely personal and extremely private.”

In recent weeks however, some of these reasons have been aired to all and sundry — by Woods herself.

Lesley Woods and the breakup

Lesley Woods could be described as a ‘character’. A recent YouTube interview with Loud Women Fest is a good primer: the wiry 67-year-old parades into shot holding her long-legged pomeranian like a camp Disney villain. “I think he’s been crossed with a deer,” she declares, pronouncing it “deeyah”.

When we speak for the first time, at first she is a little hostile. In my email, I told her I was writing about Au Pairs — the band’s origins, the split and the recent fall out — including some of the criticisms she had made in recent interviews. To Loud Women, she had claimed that her former bandmates were unhappy because she had emailed them “as a courtesy” to let them know she was reforming the band and to check if they were interested and whether they had the right equipment to do some gigs.

These were, continued Woods, “sensible questions because the promoter is putting us on at quite big gigs, they’re not like the Fighting Cocks,” — referring to the Moseley pub where the band played back in the day, with a slight smirk. “I don’t even know what they’ve been doing as musicians, if they’ve been doing anything” she added. “The ex-drummer had been playing a washboard on Facebook — he’s a bit of a clown.”

When she calls me, she’s determined to convince me she hasn’t been criticising anyone — but she can’t seem to help herself. “I meant it in more of an affectionate way,” she says. “You might agree with me, he is a bit of a clown.” She then claims Hammond, Foad and Dowsett “gang up on me as the three headed beast. It’s vile; it’s extremely upsetting.”

Despite this inauspicious start, Woods doesn’t seem to want to hang up and we end up talking for an hour and a half. The conversation oscillates between me trying to steer her towards specific memories and press her on a central claim she’s made: that she wrote all the Au Pairs songs herself, as well as much of the music. Her former bandmates dispute this.

As evidence Woods (apparently forgetting one of her former bandmates is a woman) says: “If you look at the songs and what they're about, you can tell firstly that they're written by a woman. If they want to say they wrote the songs I’d love to know which lines they wrote.”

Her big allegations aren't limited to songwriting. She claims the band’s 1983 break-up — with Dowsett leaving the year before — was because Hammond and Foad wanted more control of Au Pairs, especially the latter, who she paints as a “jealous” ex-lover, grappling with a breakdown.

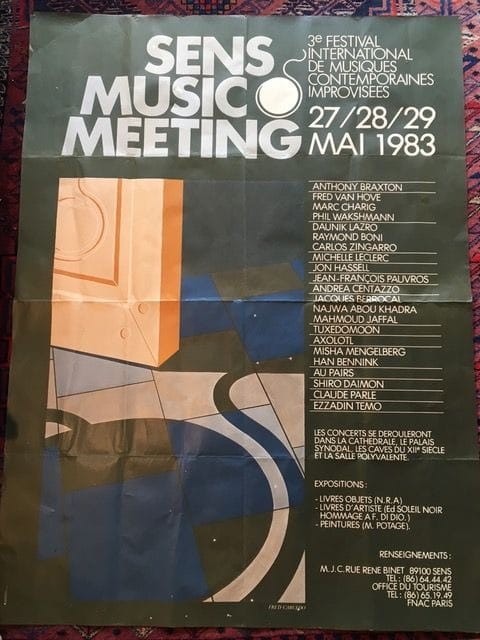

Hammond and Foad maintain this is nonsense; according to Foad, he and Woods had split up long before Au Pairs got off the ground. He did take a “short” break for exhaustion in 1983, on the advice of his doctor, he concedes. But the group was still active and booking gigs right up until the end, including an improvisation festival in Sens, France which Woods didn’t show up to.

“That is a lie,” Woods tells me, with emphasis on the word ‘lie’. “That is not true. There was never a gig in France that I failed to attend. That is a lie.”

But I reach out independently to a musician who played with Au Pairs at the festival; they recall arriving at the airport to fly to France — Woods was a no show. The group decided to go anyway. The artist still has a poster advertising the gig, on which Au Pairs are clearly listed. Woods claims that, if this gig happened, then it went ahead without her knowledge.

It’s not the only time I catch Woods out. One of the more incendiary claims she has made concerns Dowsett, and a relationship she was in at the time she left Au Pairs. The way Woods tells it, Dowsett quit the band because she wanted to start a new group with her then-boyfriend, who ended up scamming her. “She told me that she bought a load of equipment on her credit card, and she came home one day and he had fucked off with the lot of it,” says Woods.

The real story, Dowsett confides, is that she was trapped in a coercive relationship. The partner in question was obsessive, would constantly call Dowsett and show up to Au Pairs gigs unannounced. Their life together became very claustrophobic. She shows me an email she sent to Woods, dated 6 February 2020.

“I do want to set the record straight on one matter which is very personal to me,” Dowsett writes in the message. “You referred, not for the first time, to me leaving the band to ‘shack up with [redacted]’. It’s hugely ironic that while you were talking endlessly about women’s rights, domestic violence etc, you failed to notice that your fellow female band member was being sucked into an abusive relationship.”

Despite receiving this email five years ago, Woods has since repeated these claims publicly, including to a blogger who interviewed her for the Fear and Loathing fanzine. Dowsett says she asked the publication to remove the section.

When I put this to Woods, she sounds angry. “Have you seen this email?” she demands.

“Yes.”

“Well I’m sorry, I don’t know what email we’re talking about. I don’t care. I don’t care. I just don’t give a shit,” she says, growing frustrated.

In the days which follow our chat, I receive many emails and texts from Woods in which her position fluctuates between sympathy for Dowsett, and insisting she knew nothing about the nature of her relationship. This volatility appears to be characteristic but it is also paired with an undeniable magnetism. I can see why she was such a captivating frontwoman. She also has a sideline in poignancy.

“I was very much in love with Paul at the beginning,” she tells me, during our first phone conversation. “But at some point I kind of fell in love with other people.”

She asks, “Are you married?” I tell her I’m engaged and having a wedding next summer, but I enjoy my independence too.

“I think that's the thing about relationships, they do need space,” she ponders. "I think that too with the Au Pairs. The split really broke my heart, and it took me a long, long time to get over it. I think it's such a shame that somebody couldn't say ‘look, guys, what you need right now is to take some time out, like maybe a year, and then come back together.’”

The wilderness years to today

In the years after the Au Pairs ended, Dowsett, Hammond and Foad lost touch with Woods. The three of them went on to do their own thing, occasionally connecting by letter, then email. Dowsett became an aromatherapist, Foad joined jazz musician Andy Hamilton’s band, and Hammond became a freelance musician.

In 1993, 10 years after the split, Dowsett received a phone call from Woods – who was now a barrister – out of the blue. She was ringing to demand 100% of Au Pairs' songwriting royalties. “I remember being totally astonished because there'd never been any hint of this before,” Dowsett tells me. “Given the agreement that we had and the whole basis that the band had been formed on, it was just a total shock.”

For her part, Woods says she doesn't recall the phone call and that she didn’t understand the implications of the legal agreement she signed in her youth. “I was young and deliriously happy to be playing in the band so I simply took no notice,” she tells me.

According to Dowsett, the call kickstarted increasing tensions. Woods first contacted EMI, the music publishing company handling the Au Pairs’ back catalogue, and made a formal claim to the rights, leading to each member’s 25% royalties being frozen. She eventually backed down but later tried again in 2006, when an Au Pairs anthology was released.

Woods demanded the other members sign a declaration handing over the songwriting rights to her, but again retreated after a forthright letter from Dowsett, according to the bassist. Woods on the other hand, says the claim ended due to a technicality on the part of the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society (MCPS).

In 2011, Foad was on a long-haul flight, watching a movie called The Abor and was pleasantly surprised to hear three Au Pairs songs on the soundtrack. As the credits rolled, he nearly spat out his Coca-Cola. They were all credited to Lesley Woods. It transpired that she had claimed to own all the copyrights and had secretly licensed their use for £3,000.

As the years rolled by, intermittent emails from Woods arrived, following the same theme. She was demanding all ownership of all Au Pairs songs. At every instance, pushback from her bandmates — and their solicitors — quelled her mission, at least temporarily.

But when the adverts for the 2026 tour appeared this summer, and they discovered she had trademarked their band name, they had had enough. Hammond, who has been the administrator of the Au Pairs Facebook page for more than 10 years, set the record straight in a post. “I have been threatened to change the name or take down this page,” he wrote. “The advertising for this reformation/reunion is totally misleading..don't be fooled again.” Deciding to speak publicly about the furore for the first time, Hammond, Foad and Dowsett also sent out a press release, admonishing the promoters and Woods.

The ‘reunion’ is still going ahead. Relations between three quarters of the original Au Pairs and their former frontwoman are at a historic low. For the trio, it’s a matter of integrity. “My beef at the moment is that that band meant a lot to a lot of people,” says Hammond, recalling the serious topics they sang about. “I'm worried now, because people know that there's this battle going on, that people are going to think we were fake.”

Foad doesn’t mince his words. “I think [the reunion] is a con for all the people who were into the Au Pairs”.

As for Woods, she’s in her own world. The songs are hers, she insists. But she is offering an olive branch — of sorts. “Perhaps if this all dies down,” she says, airily, “at my Birmingham show I can invite them on stage to do a few Au Pairs tracks like old times.”

AGMP was approached for comment.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can contact us or visit our advertising page below for more information

After publication, Lesley Woods requested the following additions:

- she says she did not take guitar lessons from Foad

- she claims that if the Sens gig happened then it was without her knowledge

- she has no recollection of a call to Jane in 1993

- she says her songwriting claim was brought to an end by the Mechanical-Copyright Protection Society (MCPS) due to a technicality

Comments