Drink less, exercise more, stop doomscrolling...most new years resolutions are a real drag. Here's one that is both achievable and enjoyable: supporting local journalism. Take out a year's membership of The Dispatch and we'll give you two months completely free, plus you'll be supporting a small team working flat out to cover the most important stories in the city. Hit that button to get your discounted Dispatch membership.

Is fascism making a comeback? This question reverberated throughout 2025, with politicians and commentators across the west warning against the rise of the far-right. In January, Sadiq Khan wrote in the Observer that there were “echoes of the 1920s and 30s” today, and in June, Nobel Laureates and academics from around the world signed an open letter warning of “a renewed wave of far-right movements, often bearing unmistakably fascist traits”. In September, record-breaking numbers of people marched on London for Tommy Robinson’s Unite the Kingdom rally.

While fascism has mostly been kept from the political mainstream in Britain, it has had a significant number of supporters at times. Birmingham, and the wider West Midlands, have been pivotal to that story. To kick off 2026, we are publishing a series of three essays about key moments in the West Midlands during the history of British fascism. Today, leading scholar of fascism Paul Jackson writes about the 1930s, Oswald Mosley, and the birth of the British Blackshirts.

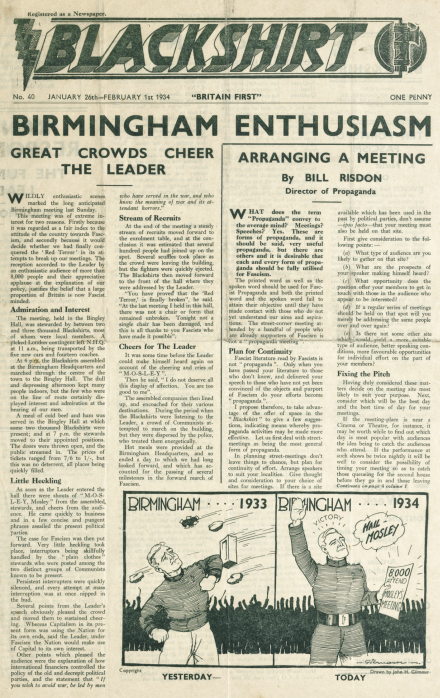

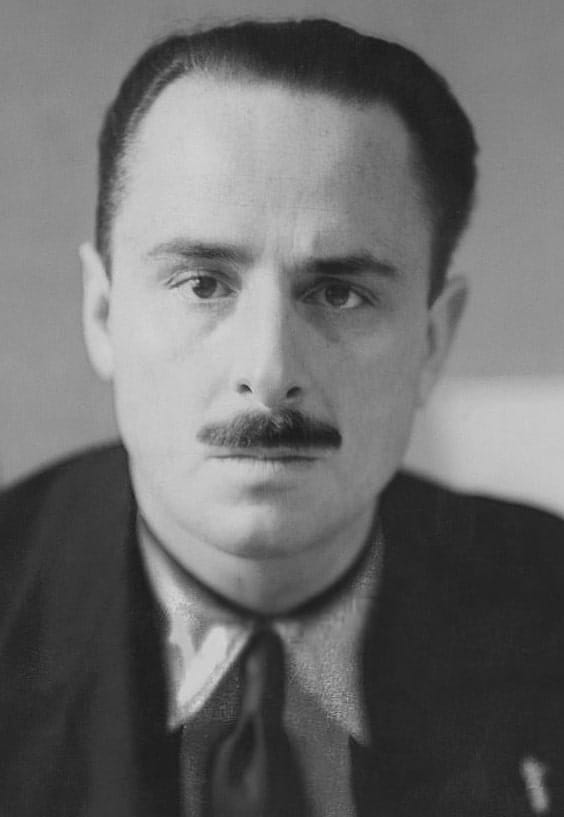

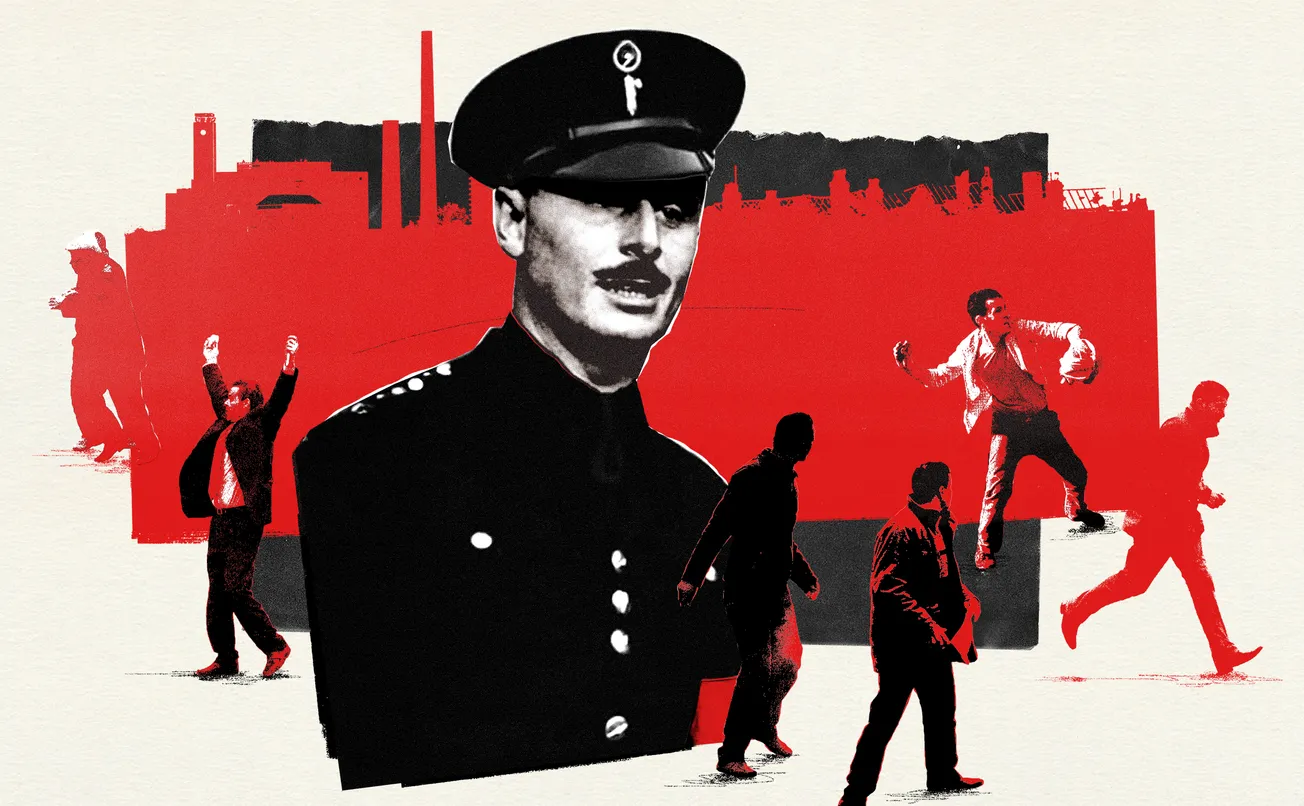

In January 1934, Oswald Mosley gave a dramatic speech in Birmingham. Thousands of Fascists, including contingents coached in from London and elsewhere, gathered at the BUF’s Birmingham Headquarters, and marched to Bingley Hall in the city centre. The British Union of Fascists’ newspaper, Blackshirt, described how, after a dinner of cold beef and ham for the party faithful, an 8,000-strong crowd chanted ‘M-O-S-L-E-Y’. Despite heckling from anti-fascists – which the Blackshirt explains was ‘nipped in the bud’ – Mosley spoke of how ‘decrepit political parties’ had failed and that only ‘the forward march of Fascism’ could make the country strong once again.

Mosley’s speech contained many of the classic messages of fascism: that mainstream political leaders are ‘old’, and are people to loathe; left-wing figures are part of a ‘red terror’, and are threats from within; and, of course, fear: fear of others, fear of economic decline, fear of attack. Mosley spoke of the threat from ‘international financiers’; then, as now, a dog whistle for antisemitism. According to Mosley, his party would ensure ‘the Nation would make use of Capital to its own ends’ and restore a sense of national pride.

The speech was a high point for the British Union of Fascists, with positive write ups in much of the press for what seemed to be an exciting new party. Mosley, with his charisma and wartime glamour, was proclaimed the man of the moment.

To understand how fascism developed in Britain, you have to understand Mosley. And to understand Mosley, you have to understand the central role Birmingham played in both his story, and the story of his party.

Mosley was a West Midlands man. He came from an aristocratic background, the son of a Staffordshire baronet. His military career in the First World War included service in the Royal Flying Corps, evocative of the dynamism and youth that he would later cultivate as a fascist leader. However, he was injured in 1915, and spent most of the war in the Ministry of Munitions and the Foreign Office.

Mosley’s turn to active politics came in the immediate aftermath of the First World War, elected a Conservative MP for Harrow in the 1918 General Election. He was soon disillusioned with the Tories and became an independent MP in 1922, before defecting to Labour. By this time, a group called British Fascists had been founded, but Mosley was not yet personally drawn to such politics.

Instead, Birmingham became a key staging post in Mosley’s political career. He stood as the Labour candidate in the Ladywood constituency in the 1924 General Election, narrowly losing to his Conservative rival, future Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain. He may not have been helped by his public profile being seemingly out of step with what was expected from a left-wing politician, complaining that he was unfairly satirised as an aristocratic socialist. (He described in his autobiography how local newspapers depicted him ‘reclining in a large gold spoon which was hoisted on the shoulders of the enthusiastic workers.’)

But Mosley was part of a generation who craved something fundamentally new after a profound, traumatic conflict. He began to develop his own radical economic ideas. He described these as the “Birmingham Proposals”, echoing the earlier radicalism of Joseph Chamberlain. They were framed as the revolutionary changes needed to transform working conditions and the nation as a whole, and were heavily influenced by Marxist ideas, with calls for income redistribution and much more active state planning.

Meanwhile, Mosley continued to make his way in the West Midlands. He was elected Labour MP for Smethwick in 1926 and became a rising star within the party. In 1929, he was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and, following the Wall Street Crash, focused on resolving mass unemployment.

Mosley refined his economic vision further and launched the Mosley Memorandum, building on the Birmingham Proposals. While 17 Labour MPs supported it, it was rejected by the Labour government, who thought the large programmes of public spending it demanded would bankrupt the country.

For Mosley, this refusal to take up his radical ideas showed that mainstream political parties would never take the drastic action needed. Disenchanted by both the political left and right, he left Labour to set up “the New Party”. The framing was a deliberate rejection of what Mosley described as the ‘Old Gang’ — the politicians he believed were holding Britain back. While Mosley had been on the political left, this call for a complete rejection of what came before was a step closer to fascism.

Ahead of the General Election of October 1931, the New Party mounted a major rally at Birmingham’s Rag Market, attracting 15,000 people. But despite its mass popularity, this was the event which sealed the party’s fate. As Mosley spoke to the crowd, suddenly the speaker system broke down. Communist and Labour hecklers could be heard at the back of the hall. Party stewards became aware of the disruption, and Mosley’s own bodyguards descended from the stage. Mass fighting broke out. Mosley’s New Party quickly became associated with the violence of his ‘Biff Boys’, and its electoral failure later that month ensured its demise.

Undeterred, Mosley moved on and created the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in October 1932, styled as a British variant of the growing number of fascist organisations developing across Europe. Birmingham was one of its most important locations. The city hosted an active branch, and there were weekly speeches by BUF activists at the Bull Ring, which the organisation claimed attracted hundreds of spectators. The BUF Blackshirt newspaper was sold in newsagents and outside factories, while fascists turned some pubs into their own local political bars. In 1933, the Birmingham branch helped the BUF expand into Coventry, Wolverhampton and Leicester, as well as moving into its new headquarters for the expanding Birmingham branch.

By January 1934, barely a year after the party’s formation, the Birmingham branch was able to mount a large-scale rally at Bingley Hall, which saw Mosley return to address the city once again. In contrast to the New Party fiasco, it was deemed a great success for the growing party, helping to show its respectability. It came a week after Lord Rothermere’s Daily Mail had published its famous article endorsing the BUF, bearing the headline ‘Hurrah for the Blackshirts!’

Early 1934 was the BUF’s high water mark. The Birmingham branch was reporting new members daily, and in February, activists in uniforms marched from Sparkbrook to the Bull Ring and attracted an audience of over 1,000.

But the issues that dogged the New Party came back to haunt the BUF when violence broke out at a rally at London’s Olympia in June 1934. The group became increasingly associated with the open aggression found in Hitler’s new Nazi regime in Germany. It continued to operate throughout the 1930s, creating a movement large enough to generate a fascist subculture in Britain, though it was never able to achieve any significant electoral successes.

In Birmingham, leading figures such as Arthur W. Ward — whose living room was where the first BUF meetings were held — and A. K. Chesterton — who became a leading propagandist for the BUF, and later founded the National Front in 1967 — were deemed so effective that they were relocated to the national centre. Changing local leadership, combined with the fallout from the disastrous Olympia rally, meant the Birmingham branch experienced a significant drop-off in support over the course of 1934.

Mosley remained a draw for the BUF in Birmingham. But when he addressed another mass meeting at Birmingham Town Hall in May 1935, itdid not lead to the same growth in interest and membership. The crowd was smaller, and it once again ended in brawls and fighting, with the local press commenting on the BUF’s culture of violence. Afterwards, the BUF was banned from holding events at municipal buildings in the city, leading Mosley to publish letters in the local press calling on Birmingham’s Lord Mayor to overturn the decision.

Antisemitism was a common feature of fascism, and throughout the 1930s, local BUF activists engaged in attacks on Jewish businesses and wrote anti-Jewish graffiti on walls. Prominent local BUF member Norman Gough’s anti-Jewish speeches at the Bull Ring became particularly notorious. In June 1937, Gough was prosecuted for his inflammatory talk under the new Public Order Act. (The Act itself was introduced after the notorious “Battle of Cable Street”, in the East End of London, where tens of thousands of fascists clashed with hundreds of thousands of counter protestors.)

Further issues arose in 1937, when the BUF cut back its support for local branches as part of a wider restructuring. But growing concerns about war in Europe also presented an opportunity. The BUF sought to attract new followers via a fascist variant of appeasement, which chimed with many. In October 1938, Mosley drew a crowd of several thousand to the Tower Ballroom in Edgbaston, where he spoke for several hours, stating the ‘best foreign policy is to be strong and mind our own business’ while claiming that his party alone would, to use the slogan of the time, put ‘Britain First’.

But after war broke out in 1939, the BUF as an organisation came to an end with the implementation of Defence Regulation 18B. This gave the government powers to close subversive organisations and imprison individuals of concern without trial. Mosley was interned on 23 May 1940, and by the end of the year, over 1,000 more were also confined, effectively ending the activities of the BUF and other openly fascist groups in Britain.

Mosley remains Britain’s most famous fascist figure – even though he was, by and large, a political failure. He met with Hitler (who, it seems, did not much like Mosley personally) and with Mussolini, who supported the BUF financially. In later life, Mosley denied the Holocaust, opposed migration, networked among continental fascist groups, but also drifted into irrelevance.

But Mosley’s legacy remains. He introduced a new type of confrontational politics to Britain, one which evoked powerful emotions. In speeches at Bingley Hall and the Bull Ring, he and his followers promised bold solutions to those who had lost trust in more conventional politics. It was the first time Birmingham played a central role in the development of British fascism — but it wouldn’t be the last.

Next Saturday, we’ll be looking at the post-war period and a lesser known but hugely significant fascist from Birmingham: the neo-Nazi Colin Jordan.

Drink less, exercise more, stop doomscrolling...most new years resolutions are a real drag. Here's one that is both achievable and enjoyable: supporting local journalism. Take out a year's membership of The Dispatch and we'll give you two months completely free, plus you'll be supporting a small team working flat out to cover the most important stories in the city. Hit that button to get your discounted Dispatch membership.

Comments