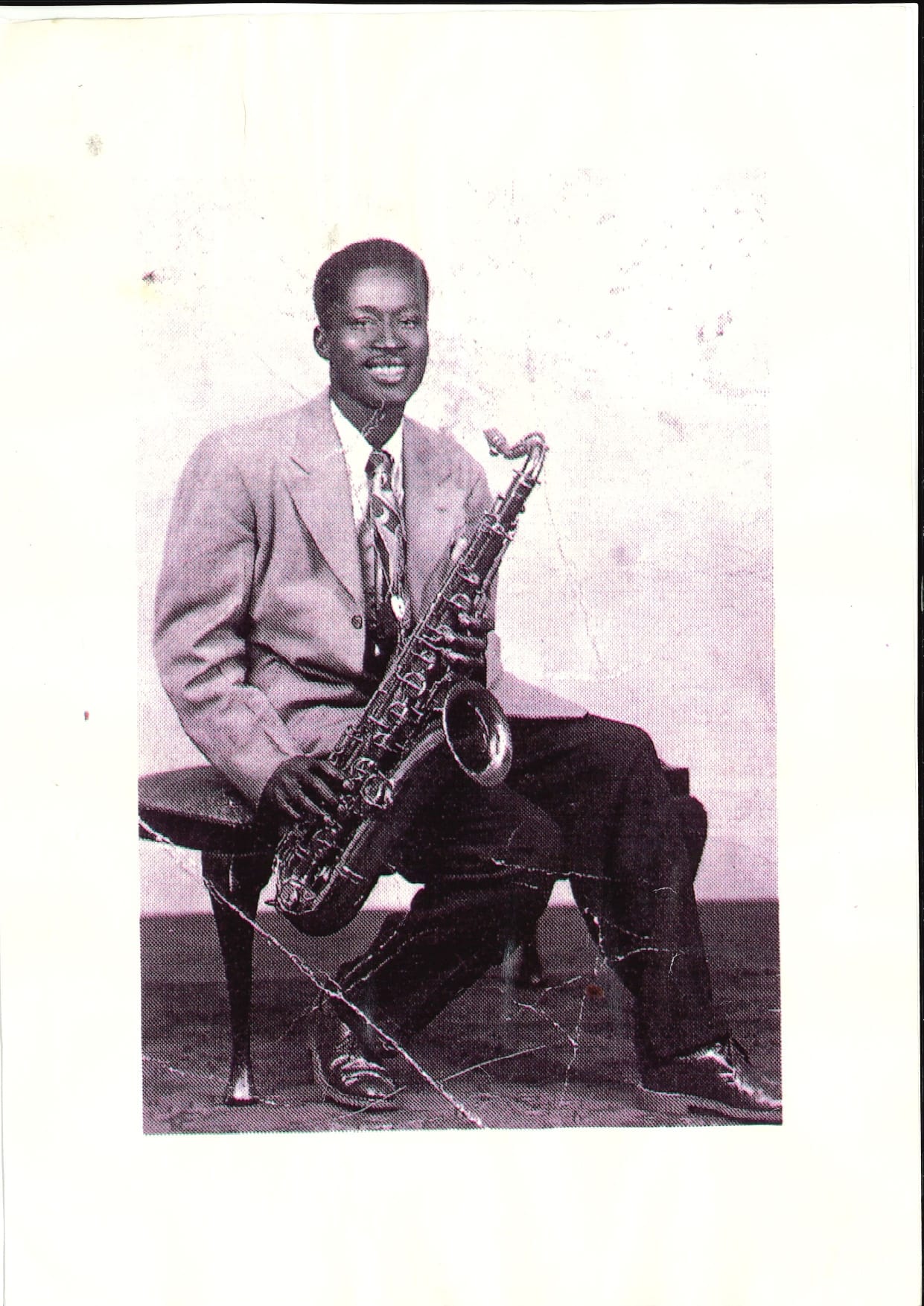

Andrew Raphael Thomas Hamilton MBE always took an ordered but colourful approach to his dressing. He regularly wore a hand-tailored suit, recalled leading jazz writer Val Wilmer, with a neat little line of delicate stitching on the lapels. The suit would be accented by a handkerchief and tie combination, the colours deliberately clashing.

Wilmer wasn't a friend of Hamilton's, but a fan: it was her review of the musician’s 70th birthday party in 1988 that played a pivotal part in Hamilton being skyrocketed to celebrity status — and a record deal — after he was of pensionable age.

But a bigger factor was Birmingham. After 1949, the city became Hamilton’s adopted home. From an estate in Ladywood, the jazz musician would go on to create an artistic legacy that still enriches Brum to this day, through the likes of community big band The Notebenders. But recognition of Hamilton’s contributions — and the fascinating details of his life — remain muted outside of his home city.

Coming to Brum

In 1949, Andy Hamilton was looking a tad less sharp, crumpled from nearly a month-long journey at sea. It had been days before he felt able to reveal himself to the crew of the banana boat he’d stowed away on as it sat in the dock at Kingston Harbour. But when they were safely past Trinidad, he’d made it known he was on board. Now, three weeks later, he could see land.

“Southampton,” one of the crew had told him, when he’d asked about the ultimate destination.

Andy didn’t know anything about Southampton. The 31-year-old knew about London and tea with the Queen, because that was what the children in Kingston’s classrooms were taught. He hadn’t wanted to leave his life in Jamaica’s capital, where his talent had seen him scouted by actor Errol Flynn to become a bandleader for yacht parties. But personal circumstances had necessitated escape. And he believed the jazz scene in England must be hotting up, maybe even more so than in the US, where he’d spent some time. The US was riven by segregation; when he’d worked over there as a labourer, he’d nearly been at the mercy of a white mob which had formed after he refused to sit at the back of a bus. But England — England was the Mother Country, they had said. It would be different in England.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

Disembarking the boat, there were two white policemen waiting for him, looking both officious and faintly ridiculous in their towering hats. “You’re coming with us,” they said, roughly manhandling him into a nearby vehicle. Andy knew he had two weeks in prison to serve, the mandatory sentence for any stowaways. But after that he’d go to the bright lights of London, find his countrymen, and start doing what he was best at: playing jazz.

Hamilton was to be disappointed when he found his fellow Jamaicans in London. Life in the capital was hard. Some were living in wretched conditions while others resorted to nefarious means for survival. London was not for him, he decided; after visiting Manchester, he ruled that out too. Instead he headed to Birmingham where industry was hungry for labour and found a place he could build a life. “I fell in love with Birmingham,” he would tell the Birmingham Post.

Sixty-three years later, he’d made such a mark that he was crowned the ‘Black Prince of Birmingham’, by Carl Chinn in a June 2012 Birmingham Mail obituary. Such a welcome wasn’t immediate. Hamilton once recalled going to a jazz club early into his Birmingham residency (at first he lodged in a Moseley house owned by Chinn’s aunt and uncle). Sometimes jazz clubs wouldn’t let him in, because he was black. But this one did.

“I remember going to a jazz club with my sax and got invited up on stage and did a couple of numbers which went down real well,” he told the Birmingham Mail. “I was really happy”.

But when Hamilton returned the next week, it was a different story.

“They just ignored me,” he said. “I went home real sad and decided the best thing to do was organise my own band and find places to play.” As a result he went on to form The Blue Notes with fellow Jamaican Sam Brown. The line up would change over the years, but Hamilton remained its soul.

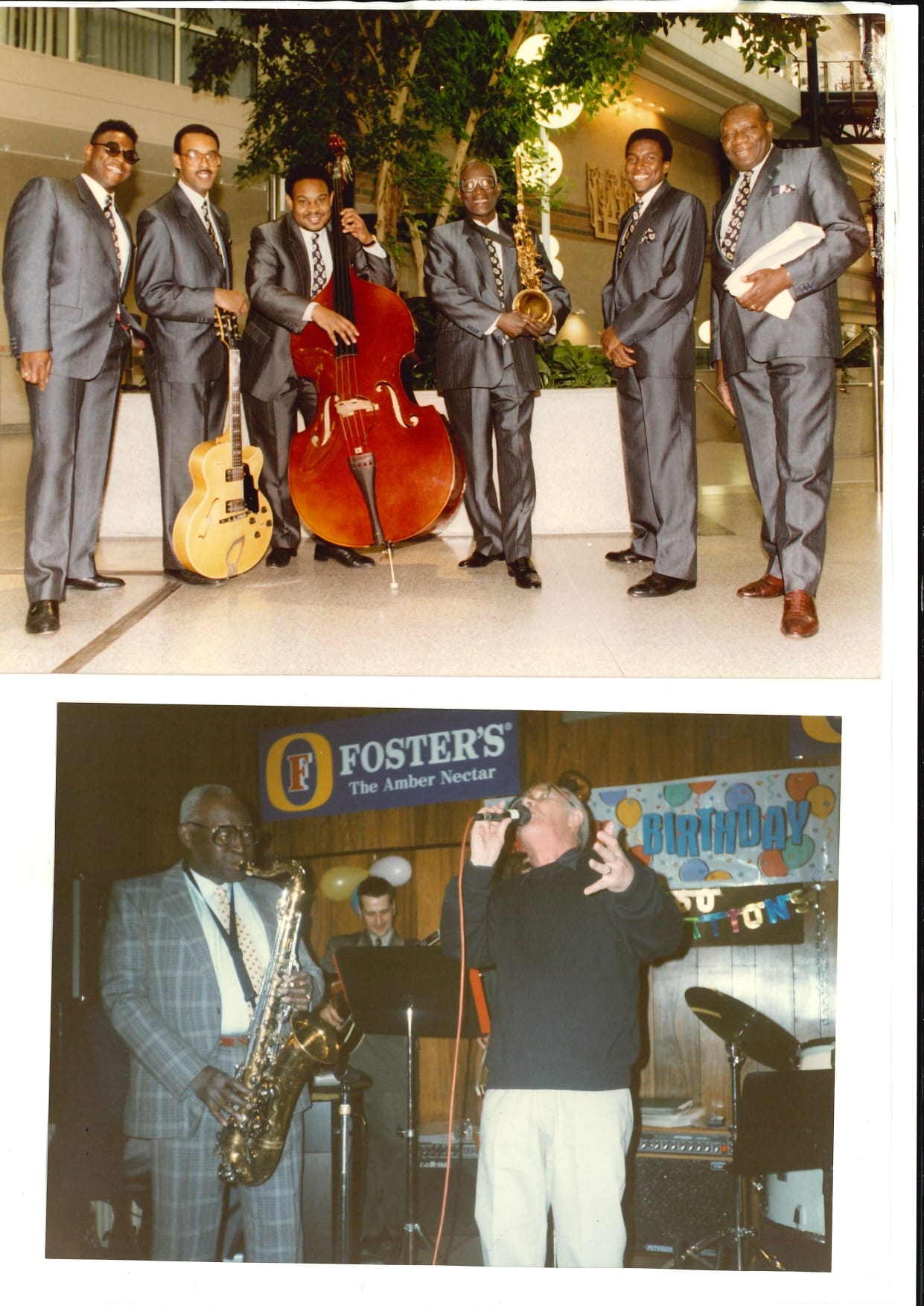

The decision to set up the band would lead to later in life success, via Val Wilmer's 1988 review for The Independent. Wilmer had such influence that the write-up earned Hamilton a spot at the Soho Jazz Festival, which kickstarted a sequence of events, resulting in Hamulton signing his first record deal in 1991, releasing the LP Silvershine. Meanwhile, his teaching work resulted in an MBE for services to music and young people, and a fellowship of Birmingham Conservatoire.

But it’s the day-to-day of his life in Birmingham which reveals the man behind the awards and accolades. Before the fame were factories. Hamilton worked as an engineer during an era of industrial decline. Redundancy sometimes loomed, and he wasn’t rich. Some of the little cash he had often went to pay the musicians he desperately wanted to get to perform in the second city. And he had a growing family with wife Mary, which would eventually number eight children.

Long hours, big rewards

Sue Pace, Hamilton’s eldest daughter, remembers her childhood in their Sheepcote Lane house as culturally textured. Instruments and records could be found everywhere and the Hamiltons would often break into dancing and impromptu ‘gigs’. Sue would regularly sit at the top of the stairs of the family house, after her father had led his usual Saturday concert at St. John's West Indian Centre, watching as musicians came back. “They’d laugh, play more, and talk about the gig,” she says. “Happy memories”.

Andy Hamilton soon became epicentre of a network that included factory workers, academics, teachers, neighbours and countless musicians, as well as Nelson Mandela, Bob Marley, Desmond Dekker, the formidable West Indian cricket team of the 1970s and 1980s, and fans and music students around the world. Its nucleus was in B16; Ladywood, where Hamilton had made his home. “He never wanted to leave that community," says Sue.

Hamilton was often away from the family home; factory hours were long and gigging took up much of the rest of it. His son, Mark Hamilton, an educator and musician who himself played with The Beat, remembers his dad played gigs most nights. “He would be getting up at five or six o'clock in the morning, working, and then gigging and doing the same again,” he says.

Those accompanying Hamilton to his gigs ate well. “Dad was always making sure he cooked food for the musicians,” says Sue. Fried chicken and dumplings were often on the menu as the band piled into a Vauxhall Bedford van to rattle off to venues. Sometimes he combined both gigs and cooking at once; at a Worcester cricket fixture, Hamilton both musically entertained and catered for the great West Indian players Andy Roberts and Malcom Marshall. “I remember thinking what an amazing day, they’re eating dad’s curried goat and then playing,” says Mark.

Other interests claimed time too. A political man, Hamilton used to rehearse at the Morning Star Communist club on Essex Street and was active in his union. “There was one set-to with management at a Perry Barr factory [with Hamilton at its centre] over stock being put in a place where the men used to play lunchtime cricket,” Sue says, laughing. Elsewhere, disputes were uglier — in the 1950s, Hamilton lost his front teeth after a group of fascists came to a blues night he’d started.

“You could see they were looking for trouble,” he said. In the break, one of the young men ventured on stage and picked up Hamilton’s saxophone.

“I went up to him, real cool, and asked him to give it back but he was drunk and punched me in the face”.

But when the police came after the incident, it was Hamilton, bleeding, with his teeth missing, who found himself arrested.

“I had to go to court,” he said. “A policeman who knew me spoke up for me and the case was dismissed”.

Racist incidents continued to interrupt Hamilton’s life. Sue remembers one booking made by a West Midlands Conservative club in the early 1970s, when the country was still reeling from Enoch Powell’s infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. The club hadn’t realised Hamilton’s band was black, theorises Sue; when they arrived, management would only let one band member go to the bar at a time. Threats via phone call also weren’t uncommon. Once, a reporter from a local newspaper turned up at the family home to ask Hamilton about mixed-ethnicity marriages.

Sue says her father’s approach was to turn the other cheek.

“He faced racism, but he was very diplomatic with it,” she adds. “He used to say no matter what walk of life, where you're from, everybody has dreams — and everyone can play an instrument.” Even those gigs at the St. John West Indian Centre, a centre primarily used by the black community, Hamilton had a different approach to. “He used to say everybody [no matter what colour] is welcome,” says Sue.

Hamilton would play any venue possible, from his longstanding ‘Jazz Every Thursday’ night at the humble Bearwood Corks, with its carpeted and parquet floors and hard leather-backed seats, to upmarket spots like the Chateau Impney in Droitwich (Andy made such good friends with the chef there, that he’d come home most Saturdays with a lobster. “Us kids were sick of it!” says Sue) and Sutton Coldfield’s Moor Hall Hotel. The latter was the site of a formative moment in the late 1960s for Hamilton. He had been struggling with evolutions in music, like the rising dominance of reggae and pop music. That Christmas, he had been booked again for Moor Hall.

The festive audience was responding enthusiastically to the lilting jazz Hamilton and the Blue Notes were playing. Then he decided to throw in a little something they’d pulled together at the last minute: a reggae cover of ‘Away in a Manager’. The crowd lost it.

“Typical [jazz] gig, it was going well and then they played ‘Away in a Manger’ with a reggae beat and everyone went wild,” recalls Sue. She thinks the gig helped her dad make peace with new music — and even embrace it.

He went onto stage Jamaican ska artist Desmond Dekker at the Town Hall and bought a ticket to Michael Jackson’s show when it came to Birmingham. “For Dad, music was about making people dance,” Sue says. There were even plans to arrange for Bob Marley to play at Tower Ballroom by Edgbaston Reservoir until his work visa fell through. Another gig at Brecon festival saw a sea of Welsh festival goers belt out Hamilton’s cover of Irish staple ‘Danny Boy’, a plaintive cry for home.

But there was only so far Hamilton would go; at heart, he was a jazz aficionado, known for hip-swaying calypso style. He turned down decent money to tour with The Beat, even though saxophonist Saxa (Lionel Augustus Martin) was a good mate. Why? Because their brand of fusion music wasn’t for him. When his son agreed to join them however, Saxa "rang my dad to say: ‘I’ve finally got a Hamilton’,” Mark laughs.

A gentle teacher

Hamilton’s unyielding allegiance to jazz also saw him turn to teaching. Locals and international students alike were taught by Hamilton; one Japanese government official sent his son specially to get tutoring from the maestro. There was the Russian musician who turned up to play with Andy in Bearwood (and who would send flowers to his funeral), and a letter from Nelson Mandela before Andy was scheduled to play in South Africa. Among Hamilton’s correspondence that Sue has kept, is one missive from a young fan, aged seven: “Dear Andy,” it begins. “I started learning alto sax four months ago and love your CD Jamaica by Night.”

Hamilton would urge young students to listen to each other’s playing if they really wanted to learn, and not to play too loud. But he’d couch advice gently, says Sue. “Okay, now I want you to play that sweet,” he’d tell students at the Midlands Art Centre, when a note was too harsh. At home, he was strict but playful, dragging the kids outside to try and see astronauts landing on the moon.

The Hamilton family legacy is felt keenly in their locality. Close to other diasporas, Mary would often act as a guarantor for Irish and Jamaican families renting. In the 1970s, Andy formed his first community big band, the Blue Pearls. And in 2001, with a grant from the Millennium Commission, he founded the Ladywood Community School of Music, making sure locals had access to music at affordable prices. The Notebenders, his surviving community big band formed in 2004, also provides members an accessible place to practice music. Notebenders alumni, such as Reuben James, now have their own successful solo careers. “It’s so nice seeing these journeys,” Sue says.

Trying to knit together the vivid strands of Andy’s 94 years on earth is no small task. As Sue says, “Dad had such a varied and enriched life.” Her brother agrees. His father’s was a “life of two halves”, with another life of fame and awards after the age of 70.

Mary Mason, a neighbour of Hamilton’s, once sat down with him to document his life. She split the recording into sections: Hamilton the musician. The migrant worker. The Black Man in Birmingham. The Teacher. The Citizen. Perhaps Andy, if the great man were around today, would add his own addition too. Brummie: one who played and lived sweetly.

Do you know Andy Hamilton's music, or the man himself? Let us know in the comments.

Comments