Dear readers — today's story is about Joseph Sturge, the Birmingham abolitionist. Sturge's life was a long-one (for the time), full of complex twists-and-turns and moral complexity. Yet of one thing he was sure: the evils of slavery. In the 21st century, Sturge's legacy is a mixed one: both radically committed to abolition, but also paternalistic and moralistic. His life, and the connections he forged between the carribean island of Montserrat and Birmingham's Edgbaston, opens up a series of questions for England's second-city. Hopefully, Jon Neale's article will answer some of them for you...

But first — your Brum in Brief.

Brum in Brief:

🚓 The woman who suffered an unprovoked knife attack near New Street Station last Friday at 21:00, has died — police confirm. Katie Fox, aged 32 from Northfield, died in hospital a few days after the attack. According to the BBC, Black British national Djeison Rafael, from Smethwick aged 21, has been charged with the attack. After Fox’s death, the charges were updated to murder. Rafael has also been charged with two separate counts of causing bodily harm on the 27th of October and the 7th of November; in addition to assaulting a detention officer. The case has been escalated from Birmingham Magistrates Court to Birmingham Crown Court.

✊ A Your Party event was held by Perry Barr independent MP Ayoub Khan on Sunday at the Royal Suite on Birchfield Road. The event was attended by Ayoub Khan MP, Jeremy Corbyn MP and Adnan Hussain, MP. Also in attendance were Akhmed Yakoob and Shakeel Afsar, local Gaza-independents who are not formally affiliated with Your Party. Yakoob has recently been charged with money laundering, while Afsar rose to prominence in Birmingham politics through a series of protests against LGBT education at primary schools.

🌎 Birmingham university students head to COP30 in Brazil. (BBC).

🚌 Councillor Liz Clements has called for the reinstatement of cheaper bus tickets (Birmingham Mail).

🥀 Two Walsall councillors have resigned from the Labour Party after a dispute surrounding a £20 million government funding scheme. (Express & Star).

🏰 The “modern fortress” that appeared on Grand Designs, Alcester Castle, is now on the market for £7.9mill. (CoventryLive).

A reminder that tickets are on sale for The Dispatch’s special festive event: our Christmas quiz! On 18 December, we’ll be heading to Temper & Brown in the Jewellery Quarter to test your knowledge on music, history, pop culture and — of course — all things Birmingham, with a £100 cash prize up for grabs.

Tickets are £4 for free subscribers and non-members (who are extremely welcome to come along). Minimum teams of two and maximum six; the winners will receive £100 in cash. There will also be plenty of time for mingling after the main business of the evening has wrapped up. Click the button below to join us; we can’t wait to see you all.

In the centre of Five Ways, surrounded by the roar of traffic and half-empty 1960s tower blocks, stands the statue of a figure in teacherly pose, dressed in the lapel-less coat of a Quaker, his hand on the bible. Below him are two female figures representing Peace and Charity, with the latter offering food and drink to a black child.

In 1862, when this marble figure was unveiled, over 12,000 locals attended. Today, it stands, half-forgotten and half-noticed, in the sunken pedestrian space which itself feels like a throwback to the subway city that largely vanished in the 1980s.

And yet this statue of Joseph Sturge, one of Birmingham’s most celebrated and controversial residents, is a monument not only to the man at its centre, but to the crucial, if overlooked role that both Sturge and the city played in bringing about the real abolition of slavery in the British Empire.

A plaque was added in 1925, perhaps to explain his significance to a population that had already begun to forget him: “He laboured to bring freedom to the Negro slave, the vote to British workmen, and the promise of peace to a war-torn world.”

The statue and the plaque are a little odd, though. They equate his unsuccessful campaigns for peace and universal suffrage, with his one victory, which led to the real end of slavery in the Empire. It’s almost as if it is trying to diminish his achievement to reaffirm the importance of the conventional story of abolition, revolving around the efforts of Westminster-based MPs.

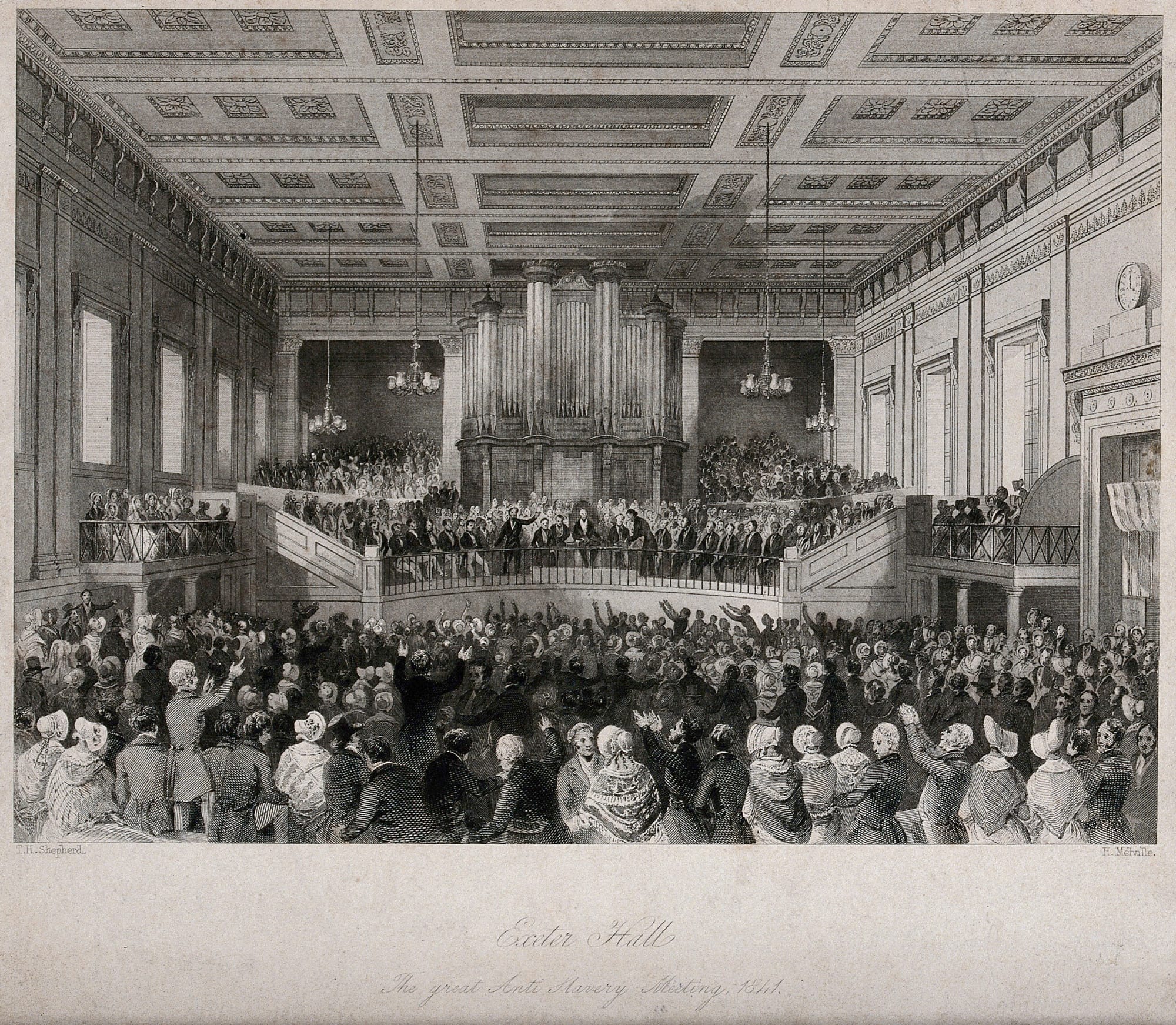

For while the mainstream account of Britain’s anti-slavery movement focusses on the ban on the slave trade in 1807 and the Abolition Act of 1833, neither are celebrated as emancipation dates in the Caribbean itself.

That is taken as the date on a different plaque, once laid on the foundation stone of the long-demolished Negro Emancipation School Rooms, in Heneage Street in Aston, but long since lost. It read: “The foundation-stone of these schoolrooms was laid on Wednesday, the 1st August of 1838 in commemoration of the abolition of Negro Apprenticeship in the Colonies, by the friend of negro, the friend of children, and the friend of man, Joseph Sturge.”

It’s easy (and somewhat reductive) to paint Birmingham as a crucible of British racism, given the city had a hand in the careers of Francis Galton, Oswald Mosley and Enoch Powell. Sturge is the antidote to that narrative. It is the opposite of Bristol’s statue to its benefactor, the slave trader Edward Colston.

This obscurity and confusion around the statue is perhaps deliberate. “While statues of slavers are among the statues Britain shows off, statues of anti-slavery activists are, in curious contrast, some of the statues Britain hides,” says the Birmingham-born academic-activist Dr Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman .

Coleman, who strikes out his name as his ancestors were given it when they were purchased in Jamaica, points out that the restoration of the statue in 2007 – and the children’s march organised by the city in commemoration – took place on the 200th anniversary of the prohibition of the slave trade, which Sturge would have considered inadequate or even irrelevant.

Middle-class beginnings

Born to a middle-class Quaker family in Gloucestershire in 1793, Joseph Sturge was drawn to Birmingham, like thousands of others from the surrounding counties, when it was among the fastest growing towns in the country. Its famous coffee shops buzzed with new and radical ideas in politics.

Sturge and his brother went into business as corn traders, setting up headquarters on Broad Street. Their offices backed on to Gas Street Basin; the canals were key to their distribution network. Their success allowed him to abandon commercial life for full-time campaigning, leaving the business to his brother. By the 1820s, he had become active in the Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery, using his contacts to raise money for the cause.

But Sturge soon became frustrated with the cautious approach of the London-based group and its leader Thomas Fowell Buxton, who emphasised slow reform and cooperation with the plantation owners. He felt that only complete abolition was in line with Christian ethics.

When Parliament voted to abolish slavery in the British Empire – at least in theory – in 1832, Sturge was outraged on two counts. Firstly, the act came with a morally unjustifiable £20m compensation payment to slaveowners – 40% of the entire government budget – while the slaves received nothing.

This story is for paying subscribers of The Dispatch. If you want to be more informed about your city, and entertained by good old-fashioned storytelling in the process, sign up for a full membership now. You get four editions a week and right now, it's just £2 a week.

In return, you'll get access to our entire back catalogue of members-only journalism, receive all our editions and exclusive news briefings, and be able to come along to our fantastic members' events. Just click that green button below. Sign up below to support local journalism.

But more importantly, the new freedom only applied the following year to children under six. All other former slaves were to be forced to continue working for their former masters for up to 12 years — this was known as the 'apprenticeship system'.

To Sturge, this was “slavery in another name.” He would continue the fight through a campaign of pamphlets, talks, marches and general agitation that was to some extent centred on Birmingham.

Birmingham deserves great journalism. You can help make it happen.

You're halfway there, the rest of the story is behind this paywall. Join the Dispatch for full access to local news that matters, just £8/month.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign In