By Jon Neale

Travellers arriving into Birmingham at the peak of the Industrial Revolution were astonished by the place. According to the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville, visiting in 1835, the city was “an immense workshop, a huge forge, a vast shop… one hears nothing but the sound of hammers and the whistle of steam escaping from boilers.” At around the same time, Giacomo Beltrami, an Italian author, wrote that there was “nothing but fire and smoke, forges and smiths… It is the empire of Vulcan.”

Yet Birmingham amazed people for another, very different reason. One unnamed traveller was surprised to find that this symbol of the industrial age was, in fact, “a town ringed by blossom”. For during the same period that Beltrami and de Tocquveille were writing, the city was surrounded by small gardens, cultivated and enjoyed by relatively ordinary working people during their brief periods of leisure. They were known as the Guinea Gardens.

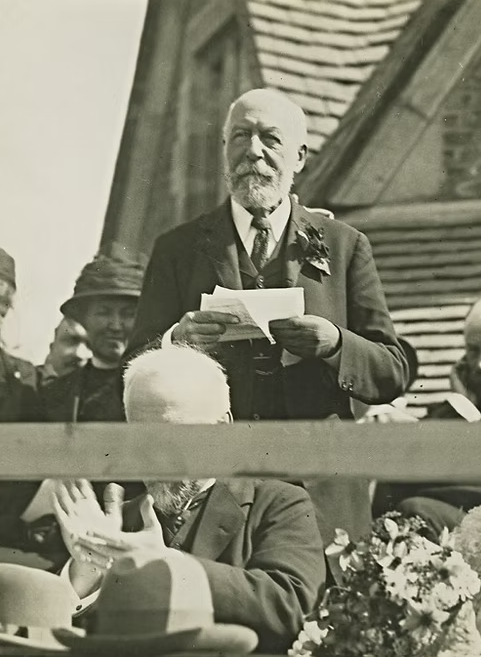

John Alfred Langford was a local chairmaker who became a journalist, political activist and poet, as well as a noted member of George Dawson’s congregation at the Church of the Saviour. He described the scene in the 1810s: “The Guinea Gardens were in very large numbers. It was a hobby with the Birmingham working man and the cultivation of flowers was carried to great perfection by him.”

The city — then barely bigger than today’s city centre and a few inner areas such as Digbeth, Hockley and Aston — was surrounded by large estates owned by aristocratic families such as the Calthorpes, the Gooches and the Colmores. It was these families who set out the plots and let them to local people, at the rent of one guinea — thus the name. The earliest examples can be traced back to the 1720s, with the number reaching its peak in the 1830s.

“There are upwards of two thousand such gardens in the neighbourhood of Birmingham,” wrote the famous horticulturalist JC Loudon, who visited the city at that time. “In one of these gardens, occupied by Mr Clarke, chemist and druggist, we found a selection of hardy shrubs and plants which quite astonished us.”

They were perhaps twice the size of most modern allotments — typically 600 square yards, or the size of a professional basketball court — and had gates and hedges rather than fences. A guinea was not an inconsiderable sum at the time, putting them out of the reach of ordinary labourers.

The tenants appear to have been artisans, craftsmen, shopkeepers, and owners of small workshops — the ‘upper working class’, as it might now be called. This was a demographic that was rather larger in workshop-orientated Birmingham than in some other industrial cities, where there might be more rich industrialists but also far more poor labourers working within factory or dock systems where free time was a scarce commodity.

While some vegetables were grown, including relatively exotic crops such as asparagus, the gardens’ main purpose was decorative. Flowers were the main features, with tenants apparently competing for the most luxurious displays. The gardens were also thick with apple, pear, plum and cherry trees, explaining the ‘ring of blossom’.

They were a source of great pride to many, and on Summer evenings and weekends, the better-off working families of the city could be seen sitting out among their plants and vegetables. The plots were passed through the generations, and the owners often invested quite heavily in the décor, with summerhouses, paths and glasshouses common features. Some even installed wells and stoves.

They were perhaps a way of showing off your status and respectability, that you had risen slightly above the norm — a role that semi-detached owner-occupation, bay windows and well-kept front gardens would perform for the same demographic in Birmingham’s outer suburbs a century later.

The Guinea Gardens were not unique to Birmingham. They were also present in large numbers in other West Midlands towns such as Coventry and Warwick, as well as further east in Nottingham. More generally, ‘detached town gardens’ could also be found in cities as varied as Cambridge, Newcastle and Sheffield, as well as London’s East End.

But where those gardens were used purely for growing vegetables for workers, in the Midlands towns, the emphasis appears to be on aesthetics: growing flowers, landscaping your garden, taking pride in it, and relaxing there during time off. And nowhere seems to have had as many of them as Birmingham.

They appear to have been highly prized and sought after, as one advert in the local Aris’s Gazette shows: “To be sold by auction — a remarkable choice garden … situated in the Avenue, leading from the Deritend Brewery to Vaughton’s Hole, is well-stocked with fruit trees selected with the greatest care and judgement… having gained first prize at the Annual Show of Fruit, abounding in choice flowers and shrubs and abundance of vegetables, a capital brick summerhouse and a well always supplied with water. The whole enclosed in a remarkably strong double fence, the soil is in high condition, and in no probability of ever being disturbed for building.”

The Guinea Gardens were in a belt around the city, with particularly large numbers in Aston, Ladywood, Edgbaston and what is now Balsall Heath and Moseley; they appear to have reached their peak in about 1830. But as the city expanded over the subsequent decades, the gardens gradually vanished under houses, although there are records of them being sold for sports grounds or development into the 20th century. They were replaced by conventional allotments which both councils and private owners increasingly began to provide.

There is, though, one surviving patch of the gardens, next to the Botanical Gardens in Edgbaston. When these were first built, a third of the site was given up for financial reasons and the Calthorpe family converted them to a set of guinea gardens. Some have been lost to railway development and to the expansion of the neighbouring Lawn Tennis and Archery Society (the oldest lawn tennis club in the world, natch) and Edgbaston High School for Girls. The summerhouses on the plots were also demolished by the council in the 1970s.

Today, the gardens are still recognisably different from allotments; with their hedges and gates, they look like miniaturised bits of the countryside, particularly in the verdant surrounds of Edgbaston. They are, unsurprisingly, oversubscribed. But as with the handful of other survivors in Warwick and Coventry, and a huge site in Nottingham, they are a reminder of what once surrounded Victorian Birmingham.

The Guinea Gardens potentially had another, longer-lasting impact on the city. For a start, Joseph Chamberlain, and in particular his close associate Jesse Collings, were major figures in late Victorian movements to provide more allotments for ordinary people. Their main concern was the plight of agricultural workers and their movement of people into the towns, but they were perhaps influenced too by their experience of seeing the gardens vanish over the century as the city expanded into the countryside.

At the same time, Quaker reformers like George Cadbury were dreaming of taking working people away from what they saw as ‘sinful’ towns, which they associated particularly with the evils of drink, and persuading them to engage in more healthy habits such as gardening. When he decided to move his chocolate factory to what was then rural Worcestershire, he was determined to set up a ‘garden village’, not just for his workers, but for any local family who qualified.

Cadbury had loved his garden at his house on the Calthorpe Estate and had wanted the same for the workers, with his chocolate replacing beer. “If it were necessary for their health that they get fresh air, it was equally to the advantage of their moral life that they should be brought into contact with nature,” he wrote. “There was an advantage, too, in bringing the working man to the land, for, instead of losing money on the amusements usually sought in the towns, he saved it for his garden produce.”

Bournville is spacious and spread out compared to later garden suburbs generally, with large gardens and plentiful allotments created by Cadbury over a century ago. A few years later, Chamberlain’s nephew, the housing reformer John Nettlefold, set up his own garden suburb at Moor Pool in Harborne, again based on the idea of “redeeming” workers through gardens and gardening. Was this all perhaps influenced by some memory (folk or otherwise) of the Guinea Gardens?

After all, Birmingham’s workforce had been drawn largely from the surrounding counties and parts of Wales. Immigrants from further afield were rather rarer than in London and some of the northern industrial cities. Did that give their preferences for home and leisure — and the paternalistic instincts of the city’s elite — a rather more rustic slant than in some other places?

There is something very Brummie about gardens and gardening. If you’ve spent time in other British cities, you can’t help but notice how spacious some Birmingham suburbs are and how big gardens attached to fairly ordinary houses can be. Terraces, too, usually have some green space at the back; there aren’t many streets with the paved backyards and rear alleys that are relatively common in parts of the North. (This also means that Birmingham is in some respects the most suburban and spread out of Britain’s big cities.)

Some of this might be explained by the fact that houses in the city, while often crowded into ‘courts’, were normally inhabited by only one family, even in the slums, with little of the multi-occupation of some other booming industrial centres. There’s also the proximity to Worcestershire and Herefordshire, two of the great fruit-growing and hop-growing counties, which offered some Brummies a chance for a working summer holiday in the countryside. The productive market gardens of the Vale of Evesham — from which produce was bought every day to the Bull Ring — meant that Birmingham was possibly more supplied with fresh vegetables than some other industrial cities. But part of it can surely be traced back to Cadbury and Nettlefold, to Chamberlain and Collings, and perhaps through that to some memory of that original ring of blossom.

A few years ago, on social media, I posted the architectural critic Jonathan Meades’ description of Birmingham as “an almost excessively sylvan place” with “lavishly green” suburbs. It was laughed at in some corners, so at odds was it with many outsiders’ image of the city as a concrete jungle. But just as with those early descriptions of a ring of blossom surrounding a core of furnaces and smoke, the city can be both these things at the same time. That split personality — industry in the garden, if you will — still partly defines Birmingham today, and is perhaps why so many people find the city a hard place to understand.

Comments