For a chain bakery specialising in honey cake and borekita, Gail’s has a surprising capacity to get under people’s skin. The opening of a Walthamstow branch last summer sparked something of a class war, with irate residents signing petitions en masse in the fear that their new neighbour would trample out the area’s independent spirit and dismantle “the character and diversity crucial to Walthamstow's charm”. It was little use; Gail’s opened its doors in October, another step in the massive expansion of a bakery so closely associated with middle-class Britain that the Lib Dems successfully used its existence in a town as a marker of whether they’d be able to pinch a seat from the Tories at the last election (Operation Cinnamon Bun, to the unfamiliar).

Next stop: Birmingham. Next week, on 16 January, Gail’s Bakery will open its doors at the junction of Needless Alley and New Street, marking the chain’s much-awaited debut in the city. Thankfully, we’ve yet to see anyone reaching for their pitchforks. Perhaps the efforts in Stirchley to block the opening of a McDonalds have allowed Gail’s to sail in under the radar. More likely there’s just less concern about “decreas[ing] visibility and pedestrian traffic towards independently run businesses” when your nearby coffee-serving neighbours include two branches of Starbucks and a pair of Caffè Neros.

Sorry to interrupt. We hope you’re enjoying this article. In fact, we hope you’re enjoying it so much that you join our free mailing list to get two editions a week straight to your email inbox. Or better yet, right now, you can get a fully-fledged Dispatch membership for just £1 a week, for the first three months.

That’s a 50% discount on four weekly editions of richly-reported narrative journalism, plus exclusive access to our events. This old school, boots-on-the-ground work takes time and money. We’ve already got nearly 1,500 people backing us with their cash. Now you can too, for less than the price of two coffees. Grab it before the end of May.

Instead, for Brummies of a certain vintage the return of coffee and cake to 42a New Street may set off all kinds of heady sense memories. For decades, this was the home of the Kardomah Café, which in its heyday was a hallmark of style and the place to plot a night on the town. Not only that, it became the epicentre of underground Birmingham, a formative place for everyone from the surrealists to the jazz crowd, from Kenneth Tynan to Lee Child, as well as a handy place to offload stolen jewellery.

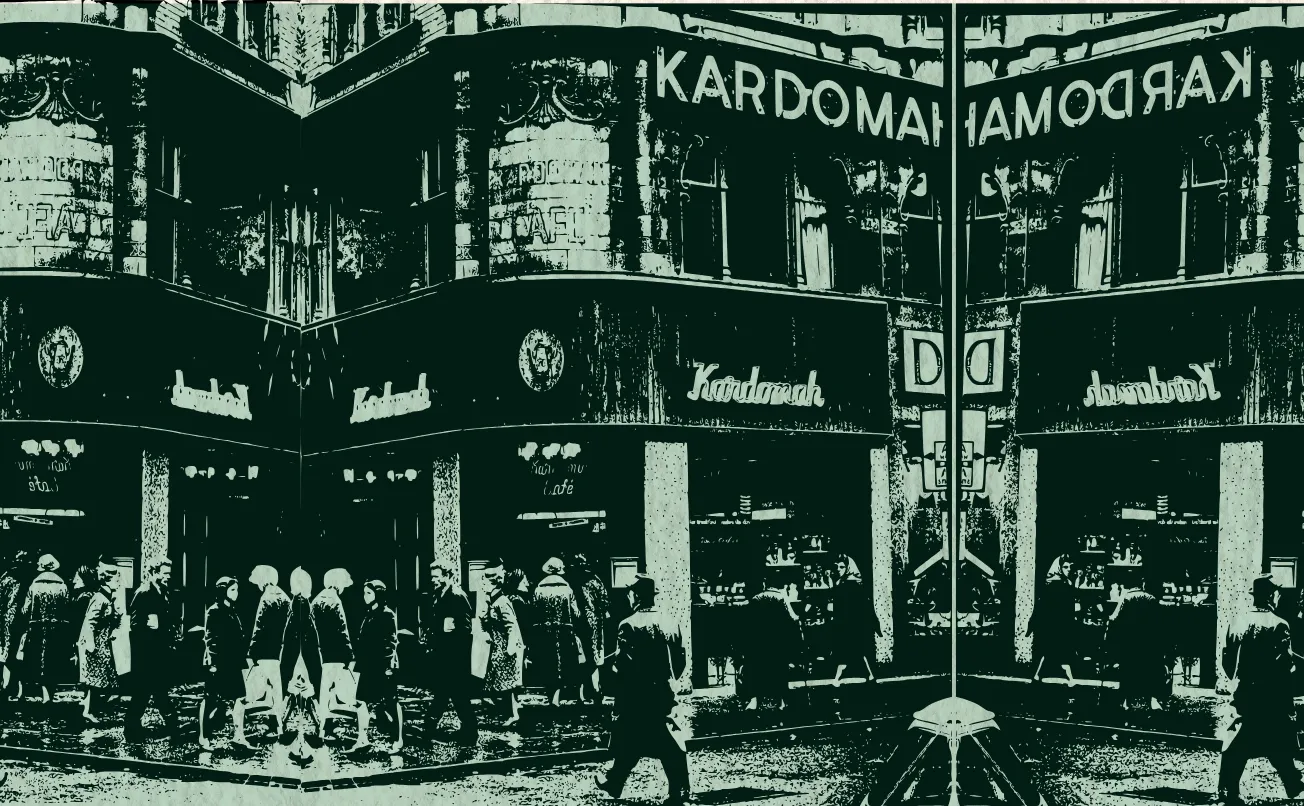

So what made the Kardomah so special? Much of it was to do with its social mix, as Anthony Everitt, arts editor for the Post, explained a few years after the café’s closure. “Most great cities have a quarter relegated to artists and criminals. In London, it used to be Soho; in Paris, Pigalle and Montmartre; in New York, Greenwich Village. In Birmingham, we order things differently,” he wrote in 1972. “Given no quarter, social outsiders are expected to fend for themselves in odd corners of the city; the respectable citizen averts his gaze uneasily or (more frequently) does not even notice what is going on.” Everitt described how “well-to-do shoppers” on the ground floor might see the Kardomah as little more than “a smart and fashionable rendezvous”, albeit one “richly decorated in an Art Nouveau style”. If they were to venture upstairs, however, they would have found “a motley collection of eccentric or suspicious looking characters” around the café’s self-service counter, arranging business deals and exchanging gossip.

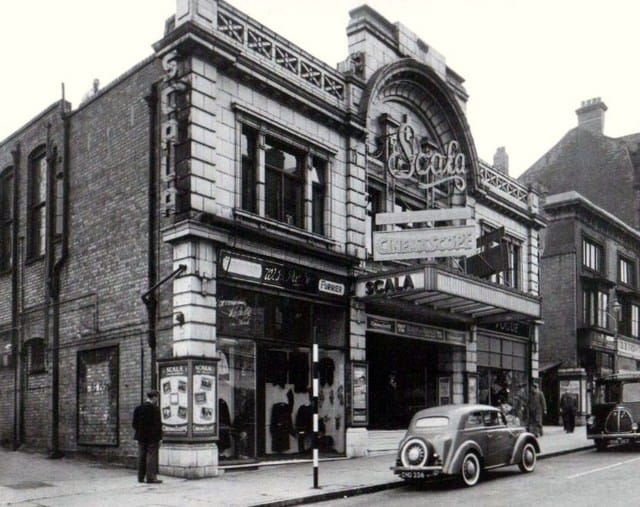

Birmingham was not the first place to have a Kardomah, nor indeed the first to make it a bohemian HQ. The brand initially emerged as a tea served at Liverpool’s Royal Jubilee Exhibition in 1887, later giving its name to a showpiece café in the city. This proved so popular that the company quickly began to expand across the country, and in September 1899 a small ad appeared in the Post: “WAITRESSES WANTED for new Kardomah Café, 42a New Street, Birmingham. Must be quiet and ladylike in manner, previous experience not essential.” The tea room would be part of a beautiful new terracotta block of offices and shops, designed in a “free Jacobean” style by Essex, Nicol and Goodman, the architects later responsible for flagship local cinemas the Scala and the Futurist.

The décor was a big part of the sales pitch — wood panelling and an elaborate fireplace downstairs, joined a few years later by a ‘Mosaic Room’ and painted murals on the first floor — but what many people remember about the place was the smell. Roasting coffee beans on the premises was unheard of at the time, and the aroma wafted all the way down New Street. The Kardomah was a destination for arty types from the beginning, thanks partly to the Theatre Royal across the road (where Boots now stands). In 1908, acting legend Sybil Thorndike agreed to marry Lewis Casson there, with the couple then marking the occasion with a romantic walk down the canal towards Five Ways. The Halesowen-born writer Francis Brett Young spent many hours in the basement as a medical student, and reproduced it as the Dousita Café in his series of Mercian novels.

In the early 1930s, a new Kardomah opened opposite Snow Hill Station. Known locally as the ‘KD’, or the ‘goldfish bowl’, it was a mecca for people-watching and tram-spotting. This may have given the New Street Kardomah the freedom to embrace its role as older sibling, rougher around the edges and with some interesting tales to tell. During and after the Second World War its reputation as the city’s avant-garde common room grew, thanks in part to it being used for meetings by the Birmingham Surrealist Group including Conroy Maddox, Emmy Bridgwater and John Melville. It was also the centre of a growing jazz scene. Singer Alan Dent told Everitt: “We objected to the austerity and conformism of the post-war years. We all had splendid parties. I suppose in some ways we were starting things which hadn’t been caught up with and banned.”

One standard-bearer for this emerging counterculture was a young King Edwards student from Edgbaston called Kenneth Peacock Tynan, who wore dyed purple suits to match his middle name. A friend described him as “a Brummagem bohemian, a shy poseur, a hard-working time-waster.” In a barrage of self-absorbed and hugely entertaining letters, he sketched out life in Birmingham on the brink of peacetime: a life-changing encounter with Citizen Kane at the Gaumont; “coitus interruptus” in the Great Western Arcade; playing Hamlet at the BMI; and the delirious bingeing that followed VE Day.

The Kardomah was the base camp for these antics, with Tynan bashing out letters, reviews and scripts on a portable typewriter overlooking New Street. Work was not the only thing on his mind. In February 1945, he wrote to his friend Julian Holland: “I am now within a pebble’s flip of a sordid physical affair with petite, enigmatic, intellectual, 24-year-old Enid (whose bright yellow hair and bitchy sarcasm you may have observed in the Kardomah).” A year later, he asked a complete stranger to recite some Noel Coward dialogue by way of audition. “Finally, [she] consented to repeat the line: but a Tipton accent betrayed her, and I regretfully returned to my table.”

Tynan had successfully buried his own Birmingham accent by that point, already at Magdalen College Oxford on a scholarship and well on his way to a stellar career as the Observer’s drama critic and infamy as the first man to say the f-word on British TV (although it appears that both Brendan Behan and Miriam Margolyes beat him to it). After he left, there were plenty of others ready to take his table on the first floor. One user of the Birmingham History Forum, who worked in the offices opposite, recalled looking across at the Kardomah: “Upstairs was a hangout for would-be writers. They would be out of the way in the afternoons after the lunch hour crowd, and not bothered by the staff as they were mostly quiet but smoked a lot. They would buy a cup of coffee and make it last.”

This seems to have been key to the café’s appeal during this period. The drinks were not necessarily the cheapest in town, nor even the tastiest, but the atmosphere was pretty tolerant and there was always a good chance you’d meet someone interesting. Maybe a little too interesting, in the case of Paul Axel Lund, a local hood who often sat upstairs with his two Pyrenean mountain dogs making deals. Lund was from a respectable Moseley family and took to crime early. He had spent the war fencing stolen goods and running guns for Haile Selassie then made hay on the black market after demobilisation.

His first big job after returning to Birmingham was a payroll heist in October 1945, from the old Children’s Hospital at Five Ways. Lund wore a US serviceman’s uniform and made his getaway on a dilapidated BSA bicycle. He changed into civvies, burnt the clothes, and by noon was “sitting in the Kardomah café talking to as many people as I knew. It wouldn’t be exactly an alibi, but it would be the next best thing to one.” According to the papers, the haul was £2,000, though in Smiling Damned Villain, the memoir Lund dictated to Rupert Croft-Cooke in 1959, it was over £7,000. “There are thieves who are as vain about their press cuttings as young cinema stars. Or new writers, I suppose? I’ve never gone for that.”

Paul Axel Lund fled the UK for Tangier in 1954 and found there another demimonde where criminals and artists mingled freely. One of them was William Burroughs, who apparently repurposed bits of Lund’s street slang in Naked Lunch. In return, Lund shopped the writer to the Moroccan authorities, wriggling out of a spell in prison by implicating Burroughs in a conspiracy to smuggle opiates. After packing in crime to run a little bar, Lund died in 1966 and is buried in the English churchyard in Tangier.

Back at the Kardomah, history does not record what happened to associates such as Johnny Trouble and Larry the Twitch, but we do know that one of Lund’s contacts, Ironfoot Jack, was arrested there after the war. So named for the prosthetic foot which made a clanking sound on the café stairs, Jack had an eclectic career as strongman, escapologist, numerologist, antique dealer and ‘King of the Bohemians.’ As he put it in his memoir: “I had a detrimental vibration. I was sitting in the Kardomah Café talking to two characters and handling hundreds of pounds worth of diamonds that I was going to get valued. However, somebody squealed, and I only had the diamonds in my possession about twenty minutes when squad cars arrived.”

Some of the café’s regulars qualified as both artist and criminal by virtue of their homosexuality. Throughout the 1950s and ’60s, the basement served as an unofficial meeting place for the local gay scene on a Saturday morning. Later in the day, the clientele downstairs would shift to more of a mod crowd, sometimes causing headaches for the staff. In March 1965 there was a near-riot in the road outside after a group of young people were refused entry to the café. The Post spoke to Gary John Warburton, area manager of Kardomah Cafes, who said that for nine months or so, there had been trouble with “crowds of teenagers” who tried to use the basement “as a sort of club.”

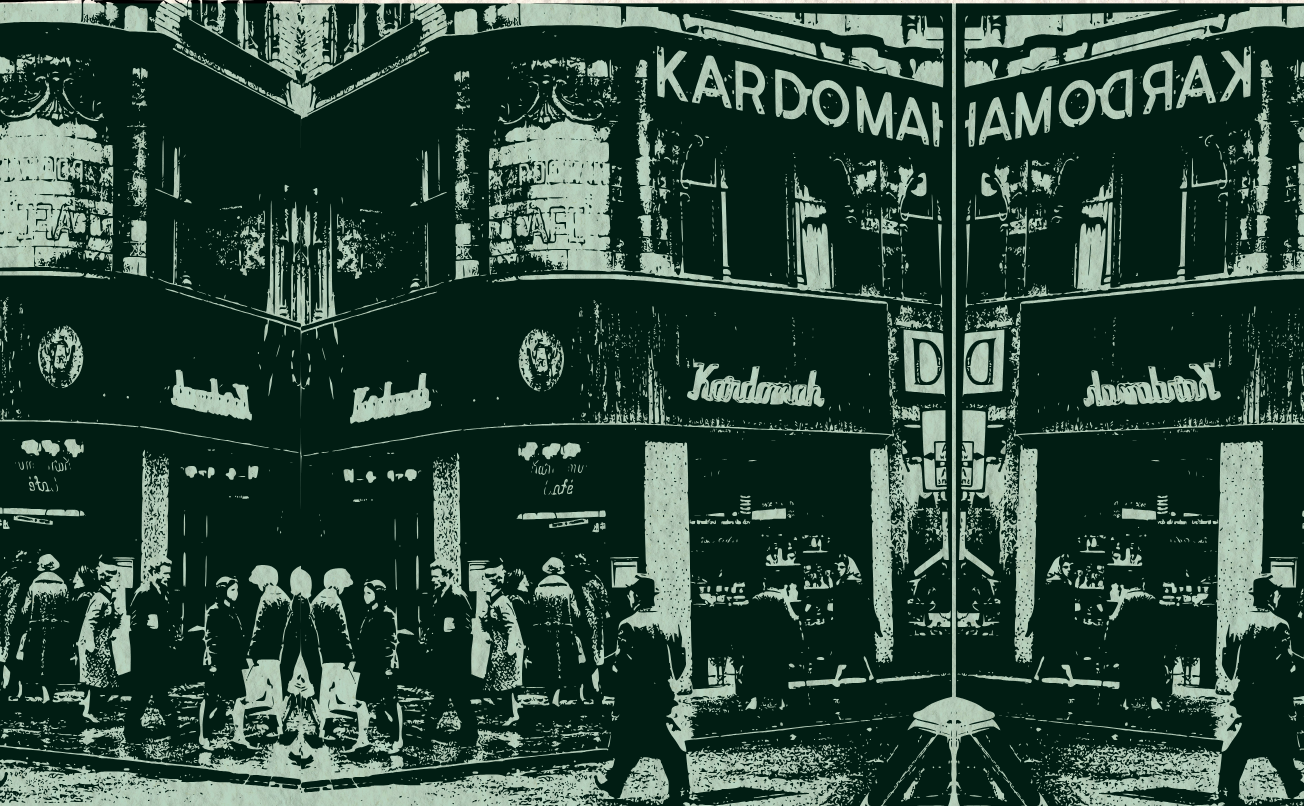

Despite the late-’50s demolition of the Royal, the café remained a site of pilgrimage for theatre people; Michael Gambon remembered taking Olivier there “for a coffee and a Danish pastry” during a run of Juno and the Paycock at the Alex in 1966. Takings were dwindling, though. By this point, Birmingham had had a taste of real espresso thanks to places like Andre Drucker’s La Boheme, which opened in 1958 in Aston Street. The Kardomah had long traded on nostalgia, but it was beginning to look like an anachronism. In 1968, the doors closed. “This is a world of disturbing changes in familiar places, and it will be a shock to find that the New Street Kardomah is no longer there after the end of this month,” the Mail lamented.

The whole building was Grade II-listed shortly afterwards, and since then the ground-floor units have hosted a consumer rights centre, a Pizza Hut, a discount jewellers and an array of menswear shops. During a refurbishment in 2017, the suit retailer Charles Tyrwhitt uncovered some beautifully preserved mosaic tiles on the first floor, and you can visit these today. (Apparently, when the upper floors were converted into apartments in the late ’90s, other parts of the mosaic were moved around the corner to the lobby on Cannon St). If you look above the door of the new Gail’s bakery, you can still make out the worn stone letters of the Kardomah sign.

The chain as a whole was in decline, and the Colmore Row Kardomah also became a Pizza Hut in 1986. Today the last surviving Kardomah can be found in Swansea’s Portland Street, up the road from the original site where Dylan Thomas and others formed the ‘Kardomah Gang’ in the 1930s. The current version, run by the same family for the past 50 years, has a neon sign on the outside by artist DJ Roberts. It’s a line taken from a radio broadcast by Thomas, in which he lists various topics of conversation covered in the café: “Michelangelo, ping-pong, ambition, Sibelius, and girls.”

Comments