By Kate Knowles

I think a lot of people lament what local news has become without really knowing why it’s become like this. That’s understandable — why should readers know what’s happening under the bonnet of an industry they don’t work in? But perhaps I can help.

It’s frustrating to find that your local newspaper is much thinner than it used to be — now full of grim crime stories and missing many of the features, reviews, and columns that used to give papers their richness and texture. It’s genuinely anger-making to visit a local news site and try to access important information as the text dances around on the page because a video ad is opening up and a flashing banner is appearing. And what’s with all the stories about something a random celebrity said on Instagram?

When you work at a local newspaper — as I did for 18 months at the Birmingham Mail — you see these frustrations all the time. You read the comments (“Must be a slow news day”, “Call this journalism?”) under your stories. You see the angry replies on Facebook where local people who may very well live in the house next to you are calling your newspaper a worthless rag.

The sound of readers’ anger boiling over is an unpleasant background hum that never goes away. Sometimes it explodes in a post on the r/Brum Reddit forum and dozens of people are suddenly making jokes about the website you work for, or complaining about the barrage of ads. “There is so much visceral disdain for the Birmingham Mail here,” one member of the forum wrote recently when someone recommended that people sign up for The Dispatch. “No thanks — I'm actually very keen to discover the latest question fans are asking about Helen Flanagan,” came one witty retort.

And let me tell you: the journalists at the Mail — or Birmingham Live as it's now better known — see all those comments. And they feel them personally. Imagine seeing random members of the public slagging off your work in public and getting dozens of likes. Would you like it? Would it hurt?

And now I’m the one doing the hurting. This week I shared a tweet from Money Saving Expert guru Martin Lewis in which he castigated Birmingham Live for misrepresenting (“this is utter bollocks”) something he had said about the National Insurance cut. “It's time these clickbait sites took some responsibility for their misleading headlines and employing content optimisers to write rather than journalists,” Lewis wrote. I retweeted his post and included it in the newsletter, because it’s exactly the kind of story The Dispatch was founded to move away from.

After I did so, a former colleague got in touch — someone who I respect and who really cares for the people they work with. They pointed out that the reporter who wrote the story (which has since been taken down) had been publicly humiliated already. Why add to the pile on? If one of Britain’s most respected public figures has called you out in public, you don’t need your former colleagues joining in the witch hunt.

Fair enough. I get what they mean. And I massively sympathise with the reporter concerned, but perhaps for a slightly different reason. Because this really isn’t a story about a reporter making a mistake. It’s a story about a company putting often young, often inexperienced reporters in the firing line every single day because of a corporate strategy. One not determined by journalists in Birmingham but by executives in an office in London’s Canary Wharf, the HQ of the media conglomerate Reach Plc. To understand what happened this week — and to answer that question I posed at the start of this piece about the state of the local news — it helps to understand Reach. It’s the company that owns Birmingham’s main newspaper as well as those in Manchester, Liverpool, Leicester, and many other places. Plus national titles like the Daily Mirror and the Daily Express.

I started working for Reach in Spring last year as a Local Democracy Reporter (or LDR) at Birmingham Live. It was a good job — the Local Democracy Reporting Service is a licence fee funded initiative set up to cover decisions made by local leaders which impact the city’s residents. The reporters work for the newspapers but the terms of the funding mean they have a specific remit: covering council meetings, planning committees and other bits of local democracy.

Being an LDR means you are somewhat insulated from the pressure to churn out high volumes of quick-to-write stories with click-worthy headlines. But very soon after starting the job, I could see the ridiculous demands my colleagues at Birmingham Live were working under. Some young writers were publishing more than ten stories in a working day, meaning they had less than half an hour to report and write each story when you take into account the time required to find photos and upload them.

Quick turnarounds were prized above stories which might take time to do a bit more digging and research. We were encouraged to rewrite the same stories from many different angles to reach the maximum number of audiences. The pressure to produce traffic meant our website had loads of news about celebrities who don’t even live in the region. These are the things going on behind the scenes that lead to the sharp decline in quality that people notice and complain about.

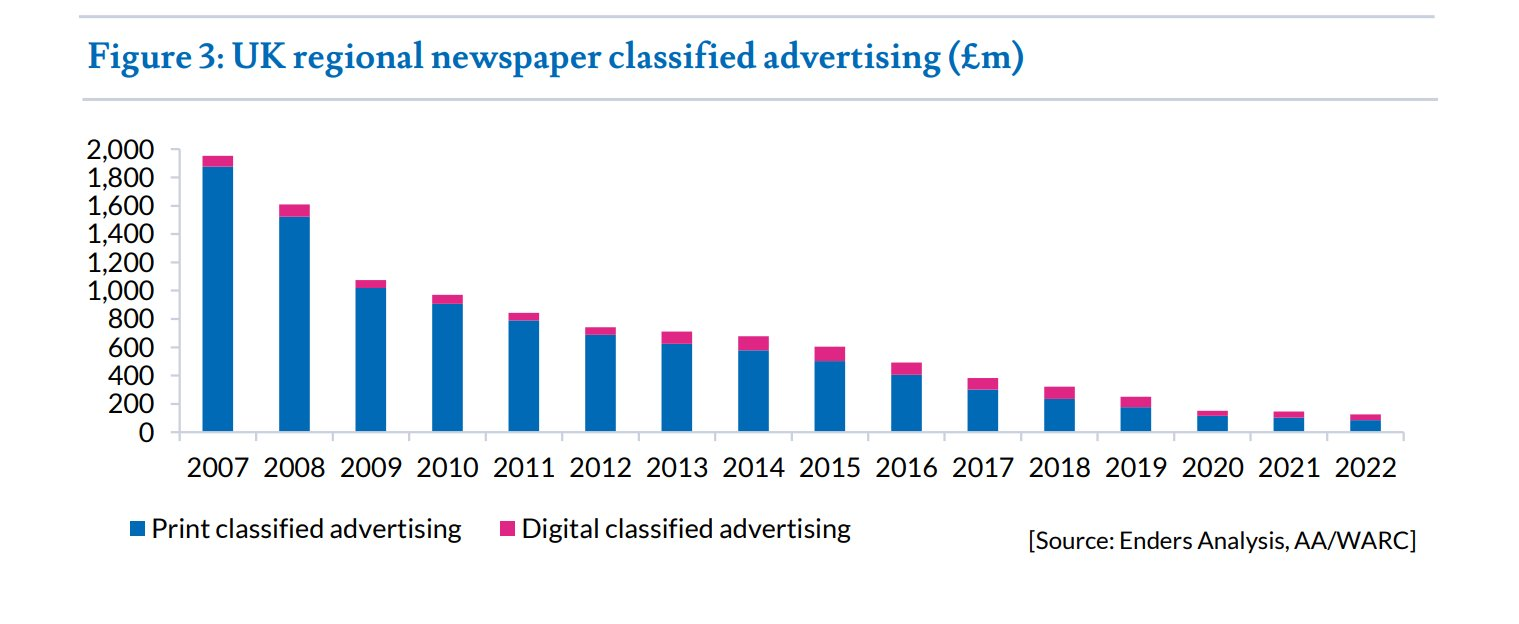

Why is it happening? A mix of big economic forces and bad decisions. In the pre-internet era, local newspapers made handsome revenue from local advertisers. Nowadays, most of that revenue has dried up: as Kirsty Bosley noted in her brilliant piece about Wolverhampton’s Express and Star, “classified” advertising in local papers (car ads, job ads, homes ads etc) has fallen 96%, from £2.1 billion in 2004 to less than £100m (see graph below). That’s an astonishing loss of revenue for newspapers and has resulted in massive layoffs almost every year across the country.

Some of those job cuts were probably inevitable as the internet blew up the old model that paid for news. But there were also glaring strategic mistakes. Instead of asking readers to pay for journalism online, just as they had been happy to pay for it in print for many decades, the companies that own most of our local news mostly decided to give everything away for free. The rationale was that the internet would allow for unprecedented “scale” — a story written in Birmingham could now reach millions of readers across the world, earning lots of advertising revenue via web pages jam-packed with ads for holiday deals, betting sites, and “one small trick for fat loss”. (The latest trend is ‘affiliate stories’ which contain links to buy products from companies paying for the privilege. If you’ve seen an unusual number of articles about top air fryers or a particularly popular M&S coat, this is why).

The market leader of this business strategy has been a company that literally changed its name to reflect its focus on scale — you guessed it: Reach Plc, previously known as Trinity Mirror. Its executives have become the nation’s traffic hackers par excellence, using famous old local news brands (and their built-in readership and all-important online “domain authority”) as launching pads to clock up billions of page views per year. Reach sites have become notorious for being hard-to-read and running some stories that have nothing to do with the local areas they are supposed to cover, while the company has repeatedly cut journalism jobs in order to maintain its profit margins (around £100m this year).

There is brilliant public interest journalism still being done by local reporters working for these sites, like this story by Birmingham Live’s Nathan Clarke about a 90-year-old woman who had to travel by bus for an hour to visit a food bank. Or Jane Haynes’ diligent reporting on the state of social housing. And the paper is committed to highlighting the chronic issue of road collisions happening across the city. But the website makes it a pain to stay on the page for longer than a few moments, which explains why the actual time that people spend on Reach’s local sites is so low (see the extraordinary graph from Enders Analysis below).

I understand the hurt that my former colleagues feel when they are criticised on Reddit or in the comments, and I get that some of them would rather I didn’t highlight these problems too. But my criticism is absolutely not personal. It’s about a corporate strategy that is remorselessly gutting the quality of news in the West Midlands and so many other communities. Reach Plc is the UK’s largest commercial publisher and the custodian of proud local newspapers. It has a responsibility to inform the public and it should be scrutinised and held to account just like we hold politicians or other powerful companies to account.

The cost to our city and our communities of this degradation of local news is clear. But I’ve seen the human cost too. I’ve seen how talented reporters and editors are tossed aside because the Reach super-scale strategy isn’t working. This happened at the beginning of 2023, when two rounds of redundancies culled 400 Reach staff within the space of three months. Birmingham lost eight people in the reshuffle, four who were made redundant and four who left and were not replaced. All this puts more strain on remaining reporters and editors, who have to do more work in less time. Then, last month, Reach announced a third round of layoffs this year, throwing the Birmingham Mail newsroom into stress and uncertainty again. “It feels like the end of days,” one Reach staffer told the Guardian. “Barring a sale to someone with the vision and investment funds that Reach doesn’t possess, the failure of the company’s business model poses big questions for the future of British journalism.”

That’s why last year I was excited to discover a small but punchy newsletter based in the place which for some reason contests our claim to be the “second city”. The Mill — started by one journalist in Manchester in 2020 — was very different. Gone were the annoying pop ups and page reloads, as well as clickbaity headlines. In their place was a much smaller quantity of stories, but a focus on quality, lots more long reads and in depth analysis.

I had gotten used to only finding this type of journalism in London-centric broadsheets and never understood why Birmingham couldn’t have it too. What’s more The Mill now had two sister publications (The Tribune in Sheffield and The Post in Liverpool), produced a weekly podcast, and held regular events.

I knew a similar publication could thrive here, so I got in touch with the Mill team and pitched the idea. Three million people live in the West Midlands and compared to Manchester, we get much less coverage in the national news while our local news has been contracting year by year. For some reason, our region gets ignored in the national conversation and our local media needs to be bigger and stronger to offer the coverage and scrutiny and celebration of local life that we need.

There has also been a bit of a sea change in publishing in recent years. After a couple of decades when it was generally assumed online reporting had to be free, digital subscriptions have boomed. Unsurprisingly, people are prepared to pay for good quality local journalism, just as they used to in the age of print. And that’s great news, because subscriptions provide the bedrock of proper local journalism. They incentivise media companies to produce great work for a local audience rather than chasing millions of anonymous eyeballs around the world. I know a paid subscription isn’t something everyone can afford, but it is how The Mill, The Tribune, and The Post have created sustainable and much-loved publications in their cities.

That’s what I want to do with The Dispatch. We will always have a lot of journalism that is free to read, providing a public service to the region. But our paying members will get lots of extra reporting about local politics, business, culture, and people in their inboxes, written by me and our growing network of freelance writers. And because we’re part of the Mill Media company, our work is fine-tuned by editors across our cities who have worked for titles like the Guardian, the Daily Telegraph and the New York Times.

It’s amazing that 4,544 readers have already joined our mailing list, and there are 71 readers pledging to support us as paying members before we have even launched our subscriptions. That’s going to happen very soon — we will open the floodgates in less than a fortnight and see whether a venture like this is something that people in this region want to fund and want to be a part of. I’m confident they — you — will. In time, I want to create a real community around The Dispatch, with live events for paying members and podcasts featuring fascinating guests.

I’ve been doing this for four weeks now. It’s hard work and sometimes involves some very late nights, but it’s also been hugely fulfilling. There’s an optimism and vibrancy about the work which is a striking contrast with the gloom of much of the wider industry. I hope readers are picking up on some of that energy — I think you are.

The short version of this article is basically this: I love Birmingham so much and I want the best for it. That includes a quality local news title befitting quality local people. I appreciate all of your support in helping us get there.

How to help me build The Dispatch:

- Pledge to become a paying member when we launch our subs. Just go to our site, log in, and then click the pledge button.

- Share today’s piece with as many people as possible. They can join the list themselves by clicking here.

Comments