Birmingham’s image is still linked to the failures of the British car industry, just as the city centre is — despite pedestrianisation, trams and the partial taming of ring roads — still blighted by the clumsy sixties attempt to rebuild it solely around the needs of drivers. And even if the car factories only dominated the city’s economy for a few decades, the story of their decline does loom larger in its recent history than almost anything else, perhaps because they employed so many, and on relatively high wages. But this legacy continues to support so many negative stereotypes about the city — its association with the sluggishness of post-war British industry, for example, or the tendency to illustrate almost any national news story about Brum with a concrete-lined dual carriageway.

But there is another story of 20th-century industry in Birmingham — one that feels far more contemporary and positive, involving a world-changing machine that was largely invented, then produced, in the Midlands. Because before Birmingham became motor city, it was the world’s cycle capital.

It is hard to get hold of reliable statistics, but apparently, at one point in 1920s and 1930s almost two-thirds of the planet’s bikes were made in the city and in surrounding towns. Aston’s Hercules was the largest single manufacturer globally.

A key reason for this dominance was the fact that the modern bicycle was largely invented in the West Midlands. Indeed, almost every single bike today globally is the descendant of the innovative machines that emerged in Coventry and Birmingham at the end of the 1800s.

During the early 1900s, when Britain’s industries were being torn apart by American and German competition, cycle manufacturing was a rare domestic success story, kept viable by a stream of innovative designs and components produced by a constellation of Midlands-based (and largely Birmingham-based) firms. In the early days of the 20th-century motor industry, despite domestic growth, Britain imported more cars than it exported; not so for bikes (and indeed motorbikes), which went some way to compensate for the trade imbalance. Like vibrant tech clusters today, it was full of start-ups and new ventures, many failures and some resounding successes — a business ecosystem that, briefly, was genuinely world-beating.

It changed Birmingham too. Many of the city’s inhabitants, especially those on the new, outlying estates built in the 1920s and 1930s, would use cycles to get to the factories that were sprouting up on the city’s outskirts. Some of the new arterial roads built in the wider area at that time — Erdington’s Chester Road, Kenilworth Road in Coventry, Stonebridge Road in Coleshill and Wolverhampton’s Stafford Road — were built with Dutch-style bike lanes alongside them. Birmingham’s streets, particularly at rush hour, must have been filled with cyclists.

These new engineering factories were also rapidly making Birmingham one of the most affluent cities in Europe. At the same time, workers’ weeks and days were becoming shorter, with some employers starting to provide paid holidays. With so many of the machines being made locally too, it’s easy to see why the city and its surroundings soon became a centre for the ‘cycling boom’. This was not just about races and other events; ordinary people, for perhaps the first time, were able to travel around the city and the nearby countryside as and when they chose. The bicycle gave them their first taste of true freedom. One local figure from a relatively modest background who typified this trend was Edward Elgar, who regularly rode his Sunbeam (nicknamed “Mr Phoebus”) — to see his beloved Wolverhampton Wanderers in the town where it had been made.

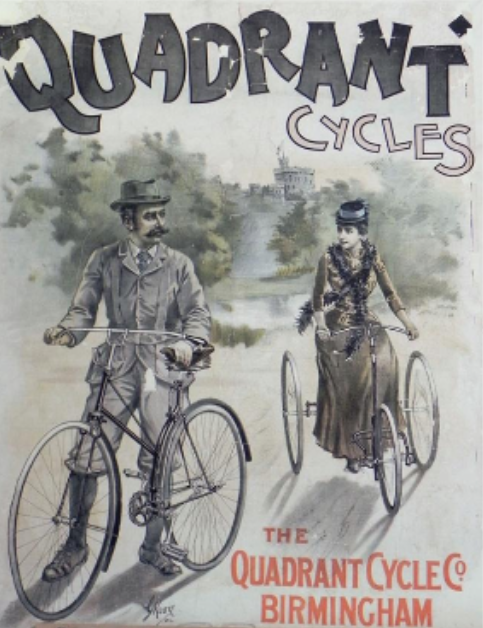

Cycling became particularly associated with female emancipation and feminism, as it allowed women — albeit largely drawn from the upper working and middle classes — to escape the confines of domestic life and travel around without men. The image of the female cyclist, often outrageously wearing trousers rather than a skirt or dress, was a hate figure in more conservative circles in the late 1800s and early 1900s, despite being widely used in advertising. Of course, all these shifts were national in scale, but it was West Midlands industry that was driving them, and ultimately they were more pronounced here than anywhere else except perhaps the rapidly developing fringes of London.

This boom, and the social changes it unleashed, was made possible by the Safety Bicycle. The first commercially successful version of this machine was created by John Kemp Starley in Coventry. Almost every bicycle being used worldwide today — off-road, gravel, road, commuter — uses basically the same design. It is no coincidence that the Polish, Belarussian and Western Ukrainian word for bicycle is rovar or rowar — Starley’s company had a bike called ‘The Rover’.

Before that, most cycles were of the ‘Penny Farthing’ variety, with a large front wheel driven by pedals directly attached to the wheel. Not only were they hard to mount given the distance from the ground, they were also unstable and dangerous, with the rider likely to be thrown over the handlebars from the high seat position in the case of any minor accident. This prevented them from becoming widely used, although they did have their own enthusiasts. But it was the much stabler ‘Safety’, with a diamond-shaped frame, chain-driven rear wheel, and two wheels of relatively equal size, that would allow cycling to be taken up by the masses.

Starley is often described as the inventor of the Safety Bicycle, which is a little too much of a stretch. There had been steady improvements in bike design over the previous 50 years, in France and the US as well as Britain. The first ‘Safety’ was designed by Thomas Wiseman and Frederick Shearing in 1869, with a few then produced by Peyton & Peyton in Birmingham, but without commercial success. Other inventors around the country were tinkering with designs too, including one Henry Lawson, who moved from Brighton to Coventry in 1879 to become the manager of the Tangent and Coventry Tricycle Company (tricycles being very popular at the time).

He then patented his ‘bicyclette’ which, despite getting a lot of attention at the main trade show, led to only a few prototypes being made — incidentally, by Birmingham Small Arms (BSA).

Other designs were tried, but Starley’s overcame all technical and commercial barriers, particularly after it was used to set a new record for 100 miles (seven hours, five minutes and sixteen seconds) in 1885.

Cyclist organisations and their campaigns had already played a major role in upgrading Britain’s then appalling roads: metalling and tarmacking, as well as producing maps and guidebooks. Birmingham was somewhat of a centre of this campaign, with Alfred Bird (of custard fame), the Warwickshire representative on the Cycling Touring Club, acting as its local figurehead. But even with better roads and safety bicycle designs, the use of solid tyres meant that cycling remained too uncomfortable for many — a major barrier to mass take-up.

Like many innovations we now take for granted, the pneumatic tyre has a history of being ‘invented’ before its alleged ‘inventor’ managed to commercialise it. But the first practical version was made by the Scottish-born vet, John Boyd Dunlop, in Belfast in 1888, trying to help his son who found tricycling on rough pavements unpleasant. Although his tyres were almost immediately used by competitive cyclists to win races easily, his patent was declared invalid because of earlier innovations.

Nevertheless, in partnership with Irish financier Harvey du Cros, he set up a manufacturing business in Belfast and Dublin, which within a few years was relocated to Coventry due to the almost immediate intense demand from the cycling industry. Soon, the Pneumatic Tyre Company bought an interest in Byrne Brothers, a rubber manufacturer in Aston, and set up “Cycling Components Manufacturing” in Selly Oak to specialise in inner tubes. (The name was changed to Dunlop Pneumatic Tyre Company when sold to financiers later in the 1890s.)

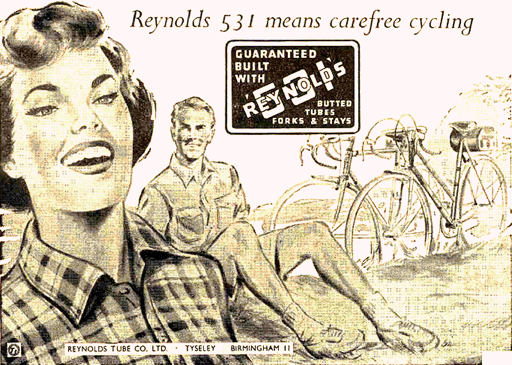

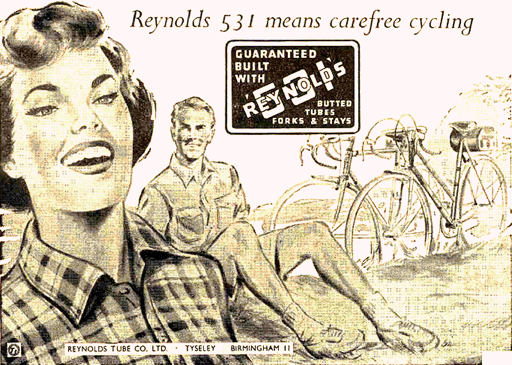

Bikes remained heavy, unmanageable affairs for a few more years until in 1897 Birmingham-based Reynolds — originally a nail manufacturer but increasingly focused on cycle frames — invented the butted tube, which allowed weight to be concentrated in the areas of greater stress. Cycles could be made stronger but built with lighter, thinner steel. Reynolds tubes would dominate the more upmarket cycling world for decades, famously used by 27 Tour de France winners.

The early history of mass cycling is littered with the names of innovative Birmingham and Midlands firms. Lucas’s range of bike lights, the ‘King of the Road’, were renowned internationally for innovative and reliable designs and eventually had to set up a factory in America to avoid import duties. Brooks was founded as a leather specialist in the Jewellery Quarter in the 1860s before moving to Smethwick to specialise in the bike saddles it is still famous for. Further afield, in Redditch —– eventually home to Royal Enfield bikes — Eadie was responsible for new types of freewheel and hub gearing systems before being acquired by BSA. (Nottingham, third place in cycle manufacture behind Birmingham and Coventry, needs a mention here too for its innovations in bicycle design as well as firms such as Sturmey-Archer and Raleigh).

Coventry, admittedly, was the place where cycling manufacturing first took off. But Birmingham very quickly took over, its history of precision metalworking (particularly in guns) easily transferred to cycle frames. As early as 1891 there were 114 manufacturers in the city, compared to 35 in Coventry and 33 in Nottingham. By the outbreak of the First World War, around 10,000 people were employed directly in cycle manufacturing in the city, with many thousands more providing the supply chain. Even Rover moved to Tyseley in 1921. Besides Hercules and BSA, other famous names included Armstrong, James, Dawes, Sun, Philips, Kynoch, Sunbeam, Saltley, New Hudson, Austin and CWS, to name a handful.

It’s remarkable that cycling manufacturing — alongside its sibling, motorcycle manufacturing — dominated the city for so long, yet so little about it is now remembered. It’s often missed out from histories of the city, which jump straight from the city of Victorian workshops to the car factories, with little discussion of the essential intermediate step provided by cycling.

But the cycling industry is key to understanding how Birmingham transformed itself from a city of ramshackle artisan workshops producing jewellery, guns, pen nibs and screws into a cluster of engineering factories. Towards the end of the 19th century the local expertise in metalworking had already led to an increasing production of machine tools such as lathes and gauges. But it was the manufacture of cycle frames and components that would really change the nature of the city and lay the groundwork for the later motor industry.

It is no coincidence that a few of the names mentioned above — Rover itself, and Austin — began as cycle manufacturers; it proved relatively easy, later, to convert factories for cars instead. Others, such as BSA and Coventry’s Triumph, would become world-famous for their motorbikes. But it seems so typical of the city and its region to ignore such a heroic part of its past; if other, more self-confident cities had this cycling heritage, what would they be saying about it?

So what happened to the Midlands’ once prolific cycling industries? Production appears to have peaked in the early-to-mid-1930s, but then domestic and global demand began to fall as mass car ownership took hold. Many companies remained vibrant well into the 1950s, but the system of import tariffs introduced from the 1930s in response to German and American protectionism had insulated the industry from international competition, making it less able to cope with the rapidly reindustrialising world of the 1950s and 1960s. Companies such as BSA, Triumph and Lucas were gradually destroyed by the combination of poor management, industrial strife and political meddling that was fatal for so many other once-great British enterprises.

From 1945 on, then-affluent Birmingham was also subject to a system of industrial development controls which effectively prevented companies from expanding in or relocating to the city without special government permission. The government felt that the industry, employment and population were too concentrated in certain “congested” areas (including, it has to be said, parts of London), and wanted to spread them out, while also moving production to the increasingly deprived areas of the North of England, Wales and Scotland.

The impact on those areas was minimal, but locally it meant that the industrial capacity of Birmingham — its factories, its machinery, its labour force, its supply of premises — was unable to grow. The motor industries were incredibly successful after the war, mainly as a result of demand from the USA, where local production could not keep up with its economic boom. As a result, more and more of the now-fixed industrial capacity and workforce of what had once been the ‘city of a thousand trades’ became focused on that one industry. Others that had made up perhaps the most economically diverse industrial hub in the world — including cycle manufacturing — withered. This left Birmingham and the Midlands almost uniquely vulnerable to the economic shocks of the 1980s, although the motor industry had already begun to struggle with mounting international competition.

While most of the names listed in this article are either long gone or since famous for other products, there are still some traces of Birmingham’s erstwhile status as the world’s cycling capital. Brooks still makes saddles in Smethwick, though it is now owned by an Italian company. Dawes, which remained relatively successful far later than other local cycle firms, still designs bikes from its headquarters in Castle Bromwich, even if the actual machines are made in Asia. Reynolds is still iconic and still makes tubes from its base in Hall Green.

Pashley has seen something of a renaissance, particularly its women’s ‘Princess’ bikes with front wicker baskets. It did, however, relocate from Aston to Stratford-upon-Avon in the 1960s. Given its all-too-English appeal, it perhaps understandably now likes to emphasise its proximity to Shakespeare’s Birthplace ‘on the edge of the Cotswolds’ rather than its roots 20-odd miles to the north. Halford’s, founded in 1892 in Birmingham as a general ironmongery but taking its name from its first cycle shop, on Leicester’s Halford Street, still has its headquarters in Redditch, despite many changes in ownership. But there is one sign, albeit small, of a local revival: in 2020, Birmingham Bike Foundry and Vulcan Works, now based on the Pershore Road in Stirchley, teamed up to provide a custom bike manufacturing facility with the explicit aim of restoring the city’s cycling heritage.

Nevertheless, while Coventry has some pointers to its place in cycling history — its transport museum, for example — there is very little to commemorate Birmingham’s once globally dominant role. Hercules the Lion, Aston Villa’s mascot, perhaps — but how many Villa fans know about the company he is named after? The city needs to stop being so coy about such a central part of its relatively recent history.

Perhaps rediscovering this part of its past would help break that association with failing post-war industry and car-orientated town planning and promote cycling in a city that seems to be lagging in enabling and encouraging it. After all, earlier this year, a survey found that Birmingham had the lowest level of active travel (walking and cycling) of any city outside North America. It doesn’t have to be that way. In the future, I’d like to see those dreary dual carriageways that accompany every national news story about Birmingham cast aside and replaced with tree-lined boulevards populated by smiling cyclists. After all, that’s our heritage.

Comments