One of my earliest memories is from the old Birmingham Science Museum on Newhall Street. I don’t remember much about the exhibits or the building, except for one thing: the Smethwick Engine. I used to love pressing the button which would make the world’s oldest operating steam engine, made by Matthew Boulton and James Watt in the 1770s, turn around. According to my mother, I would insist on going there every time we were in town. (The other childhood memory of the 1980s city centre is Rackham’s toilets, the only place that my Nan — who used to work there — would consider going if any of us needed the loo).

My family’s bookshelves were not well-stocked but there were a few ancient A4 hardbacks with titles like “How Birmingham became a great city”. In a time without phones — and my ZX Spectrum had yet to arrive — I used to spend hours flicking through these (as well as the encyclopaedia), not quite knowing what I was looking at or reading about. But I did acquire the vague notion, without quite knowing why or how — one that I think many Brummies share — that this part of the world had been singularly important in something called ‘The Industrial Revolution’.

In the mid-nineties, I was at university in Leeds with whatever the collective noun for Mancunians might be (a “swagger” perhaps?). Alongside references to the Stone Roses or the Hacienda, or perhaps the Suffragettes or Peterloo, it was not unknown for them to drop into conversation the fact that their city was where the Industrial Revolution began. My protestations that such a claim was Birmingham’s to boast about were met with bafflement or mockery – usually both. I’ve had similar exchanges, albeit more civilised, in my professional life since. So what is the truth? Does either city have a better claim? Let’s settle this now…

It is worth mentioning, first of all, that the United Nations recognises neither city as key to the industrial revolution, opting instead for Ironbridge Gorge in Shropshire and the Derwent Valley Mills in Derbyshire. In fact, UNESCO is most strident about the former: “The Industrial Revolution had its 18th-century roots in Ironbridge Gorge and spread worldwide, leading to some of the most far-reaching changes in human history.”

Ironbridge might be 30 miles west of the city, but with a bit of digging it’s possible to use it as evidence for Birmingham’s claim as the industrial birthplace. It was here, in 1709, that Dudley-born Abraham Darby set up the world’s first coke-fire blast furnace, setting humanity on a new course of industrialisation. But Darby didn’t work as an apprentice in Dudley – he worked in Birmingham, in the brass mills of Jonathan Freece. These mills were used to grind the malt used in beer, and Darby would have seen coke being used in malt ovens. That apprenticeship was critical, then, to world history – and it happened because Birmingham’s industrial growth began before the textile towns of the north had even got out of bed.

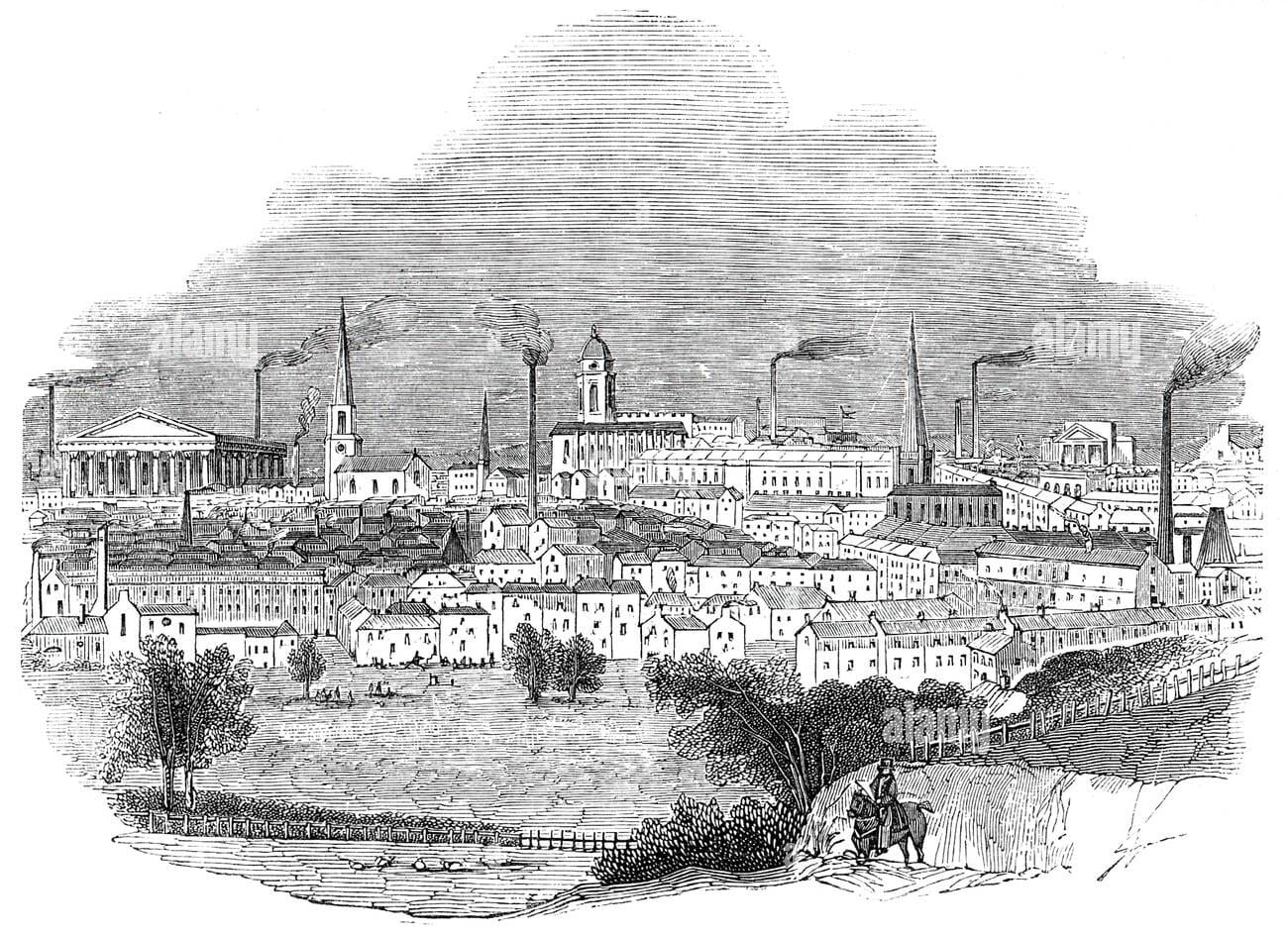

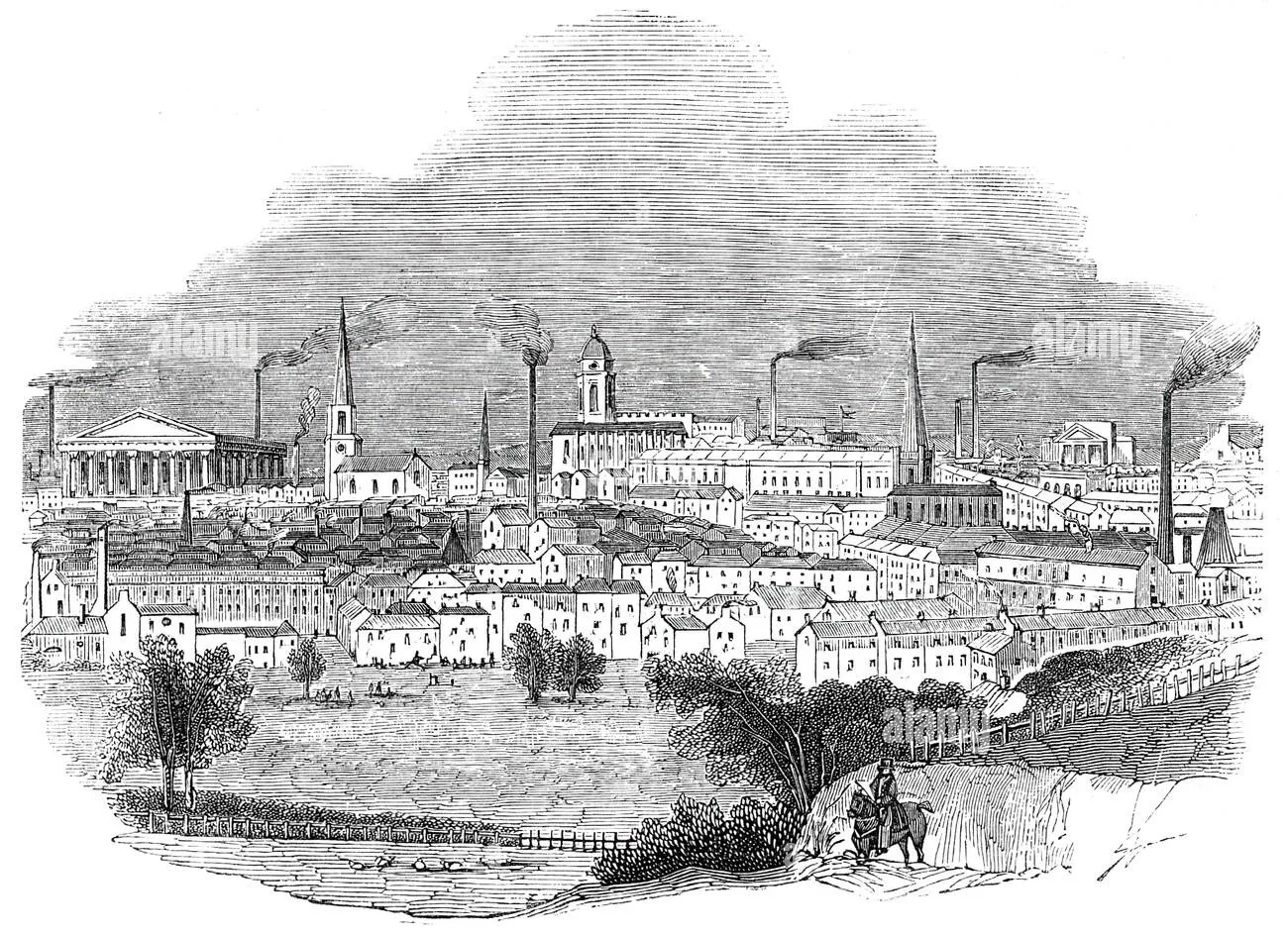

Between 1650 and 1750 it grew sixfold. By 1700 it was the fifth largest city in the country, and by 1750 the third largest — only Bristol and London were bigger. In 1791 it was named the “first industrial town in the world” by the economist Arthur Young.

The growth had been driven by several factors including the growing European market for ‘toys’ — buttons, pins, snuffboxes and so on — that went hand-in-hand with the clothing trade and also for ‘japanned’ goods (the name given to objects with a shiny, lacquered finish). A manufacturer called John Taylor, whose business in all forms of toys grew throughout most of the 18th Century, became the ‘principal manufacturer’ of the town to the extent that he employed as many as 500 people at two sites in Birmingham, where according to one observer, the goods apparently went through “70 different operations of 70 different work folks”. That is to say, there was a division of labour.

This method of manufacture had existed for a long time across artisans working in neighbouring areas and workshops, but what was revolutionary here was combining those processes under one roof. Consequently, Taylor’s operation employed one of the first factory systems in the country although a lack of detailed records means other similar ventures — such as a water-powered silk mill in Derby — can be dated to an earlier point. Regardless, if these observations are correct, this was perhaps the largest industrial operation in England at that time. At this point, we are still several decades before there was a single cotton mill in Derbyshire, let alone in Manchester.

One factor mitigating industrial growth in Birmingham was its geography (landlocked) and poor communications infrastructure (roads unfit for any purpose, let alone the increased traffic needed for the manufacture and transport of goods). The area around the city had historically been marginal, a heavily wooded plateau of isolated hamlets and smallholdings which had never been heavily settled or cultivated. The medieval economic centres of the West Midlands were further southeast, around the ancient settlements of Coventry and Warwick and the heavily farmed Feldon on the other side of the Avon, and around the cathedral cities of the fertile Severn vales.

The game changer was the canal boom, with Birmingham’s first example dating from 1769. Admittedly the first had been constructed in Manchester a few years earlier, but Birmingham rapidly became the centre of the network, with the highest concentration of man-made waterways in the country. This enabled a greater variety and quality of goods to be traded nationally and internationally and Birmingham’s industrial products would soon become famous throughout Europe – indeed the continent would remain generally more important than the Empire as an export market for much of the city’s history.

By the late 18th century Birmingham was not just an industrial centre. It was also a crucible of ideas, experimentation and entrepreneurship where religious nonconformists could freely worship, craftsmen could practice without guilds and the latest political and scientific ideas were discussed in lively coffee houses. As the historian and novelist Jenny Uglow argues in The Lunar Men: The Friends Who Made the Future: “Freedom was built into Birmingham’s self-image. Its citizens boasted of its industry, its independence and its power…. [it was] just as much a city of the Enlightenment as Bath, or Edinburgh, or Bordeaux.”

The subject of the book, The Lunar Society, counted industrialists such as Matthew Boulton, James Watt and William Murdock as members, but the group’s collective fascination with ideas and politics is why it is seen as the beating heart of the Birmingham / Midlands / Industrial Enlightenment. The activities of this group were the key link between the scientific revolution of the 18th century and the industrial revolution that would truly get going in the 19th. One of the symbols of this was the Watt steam engine, introduced commercially in 1776.

James Watt was not a Brummie but a Scot who had migrated south to work with the greatest entrepreneur of the age, Matthew Boulton. Watt did not invent the steam engine — that accolade must go to Thomas Newcomen in Cornwall — but he did introduce condensers and other improvements to its design meant it could be used anywhere rather than in locations with appropriate topography and water supplies.

Boulton set up the Soho Manufactory in Handsworth –— the largest productive unit of its time and a place visited by aristocrats and businessmen from all over Europe — before moving onto Smethwick’s Soho Foundry. This, the world’s first engineering factory, was where the science museum exhibit that inspired this piece was made in 1779. IT was originally used to pump water uphill to enable the locks on the Birmingham Main Line canal to operate properly.

Boulton and Watt would sell their steam engines to the emerging cotton mills of Manchester, where Peter Drinkwater was the first to install one in 1789. But perhaps more important than the steam engine was the duo’s commercialisation – with William Murdoch – of gas lighting. Their first installation, at Philips & Lee’s mill in Manchester in 1806, allowed 24-hour operation for the first time – and soon spread to other mills in the city. Manchester was now out of bed and getting dressed.

In 1881 the patent office Richard Prosser — who had been at school with Joseph Chamberlain — assembled a record of patents lodged in Birmingham, Manchester and Salford between 1760 and 1850. He concluded that during the 18th Century his hometown had produced three times as many patents as the other two centres combined, making it by far the most inventive city of the period. This would change in the 19th century, but it is undeniable that the uniquely innovative and inventive atmosphere of the Midlands Enlightenment had produced concrete changes elsewhere.

Can we therefore consider Birmingham’s status (and that of the wider West Midlands) as the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution to be unassailable?

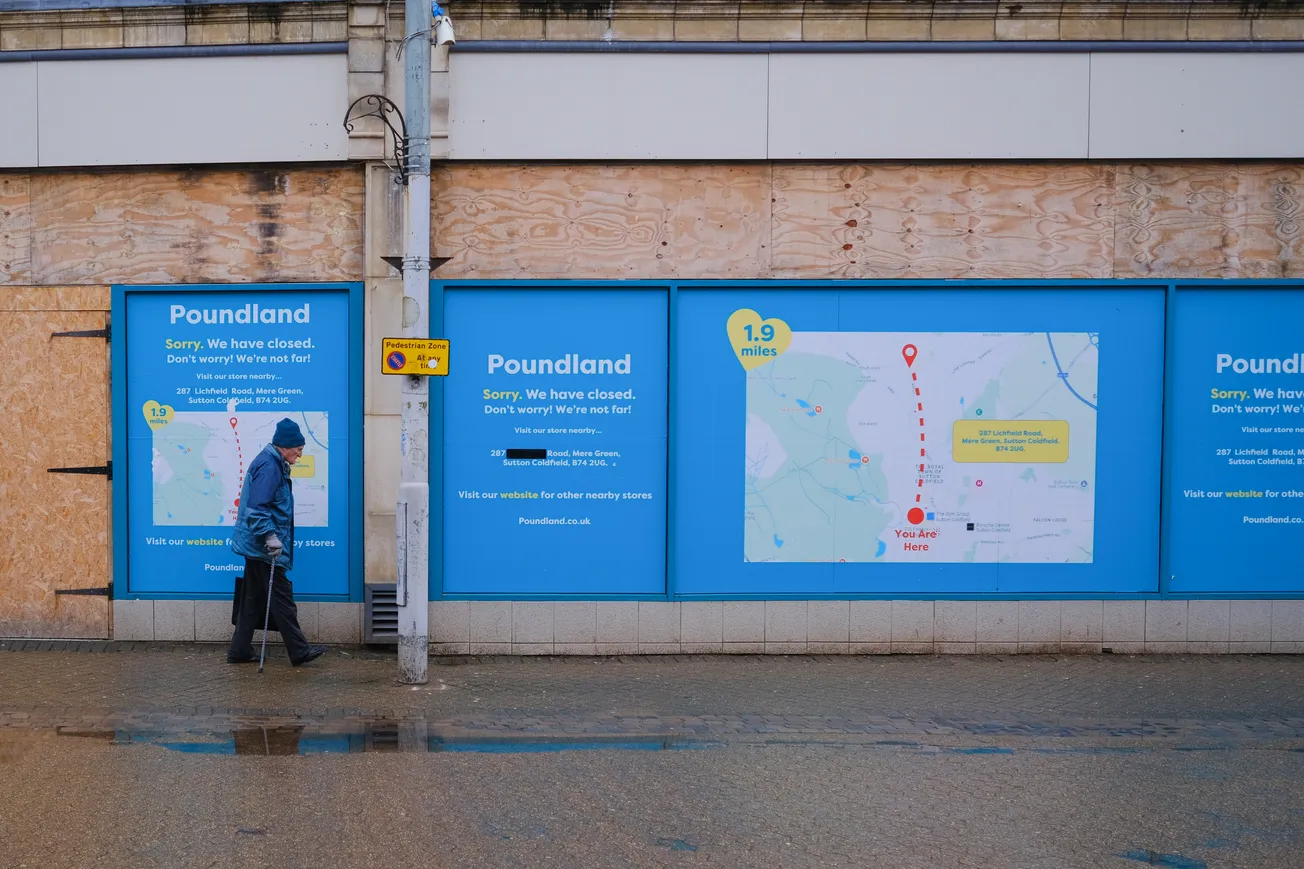

Well, there are two problems here: The first is that Birmingham’s innovations had little effect on the city itself, which remained a city of small workshops producing metal items such as jewellery, pen nibs and screws, and the second is that Birmingham’s manifold artisan industries were simply not suitable for early mechanisation. So, when economic historians look at Birmingham throughout the 19th century they are unable to detect any notable increase in productivity.

The steam engine is a case in point. It was barely used in Birmingham itself and found far more homes in the mines of Cornwall and the textile mills of the North. Another good example is the Upper Priory Cotton Mill in Birmingham. Opened in 1741 near Old Square, it pioneered ‘roller spinning’ and was the first mechanised cotton mill in the world. It was a commercial failure, but the central idea was later reused by Richard Arkwright as part of the Water Frame – the key element in the cotton mills that he would build in Derbyshire’s Derwent Valley, triggering the textile boom of the North.

Indeed, the whole idea of the industrial revolution as a leap forward across a multitude of industries has been challenged — notably by the late Nicholas Crafts of Warwick University who argued that such seismic change was only felt in the cotton industry and perhaps some aspects of the iron industry. Other industries – such as those that dominated Birmingham — remained quite traditional and did not see any great technological advances. Perhaps this is why the idea of the early Victorian Industrial Revolution has been erased outside the cotton mills of Lancashire and perhaps the blast furnaces of the Black Country or South Wales.

Crafts’ conclusions were challenged at the time by fellow Warwick economic historian Maxine Berg who argued the case for a broader definition of the industrial revolution, on that placed a greater emphasis on understanding the roots and mechanisms of technological change, rather than simply looking at economic output. This would surely have put the West Midlands back in the centre of the frame, but nevertheless it is undeniable that it was in Victorian Manchester than the Industrial Revolution – and its symbols – really took physical shape. “ It quickly overtook Birmingham in terms of population and economic heft as cotton became — by some distance — Britain’s most important export industry.

The order in which Victorian industrial towns became official cities perhaps demonstrates the hierarchy of the time — Manchester in 1853, Liverpool in 1880, Birmingham in 1889, and then Leeds and Sheffield in 1893. Indeed, if we revisit Prosser’s calculations, by the 1820s Manchester’s patent numbers were already catching up with those of Birmingham, and during the subsequent two decades far outmatched them.

This also created quite different economic structures within the cities, demonstrating that the industrial revolution was also touching lives, culture and social structures. As the French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville noted, “At Manchester, some great capitalists, thousands of poor workers, next to no middle class... the workers are gathered into factories by the thousand — by two thousands — three. At Birmingham, few large industries, many small industrialists…. the workers work in their own houses or in little workshops in company with the master himself.” The class system in classical form had emerged in Manchester, but remained more traditional in Birmingham — with ramifications for the distribution of power that was much more difficult for Birmingham's more modest elite.

The North West — including Liverpool, a vital cog in the cotton trade — developed a strata of rich industrialists (or “great capitalists” as de Tocqueville saw them) who had the political and economic heft to influence politics in a way that was much more difficult in Birmingham. This also attracted international emigres, notably Nathan Meyer Rothschild and Frederick Engels. This not only meant that Manchester was always more cosmopolitan than Birmingham, it also meant that its economic structure — with huge division of the classes — became identified with the rise of capitalism. It also partly explains why working-class politics, and trade unionism, were stronger in the north.

Things, of course, would change. Later in the century, the factory system did transform Birmingham and industrial processes became more streamlined as engineering boomed in what was called the ‘second industrial revolution’ by the Scottish biologist and sociologist Patrick Geddes (and by many since). It was during this period that the West Midlands’ manufacturing sector finally saw the ‘leap forward’ that the cotton industry had experienced several decades earlier. This, in turn, produced richer factory owners such as Joseph Chamberlain who had the time and resources to shape national as well as local politics.

There is, however, another aspect to the different tracks of industrialisation that is perhaps mentioned less but still has big ramifications today. The cotton industries began moving out to surrounding towns such as Oldham and Rochdale from a relatively early date in search of cheaper land and labour and as Manchester became less an industrial city and more the business capital and showroom of the cotton trade. Not only did it gain grand warehouses and offices, it also developed as a stronger regional capital than Birmingham — it was surrounded by cotton towns that had their own identity but gravitated towards Manchester.

Birmingham’s relationship with its hinterland was different. The Black Country had generally specialised in the heavier, cruder types of metalworking; Birmingham more in the higher value, finished goods. Their fortunes did not move together like the cotton towns, especially as Birmingham’s engineering industries took off and links were developed with rapidly industrialising Coventry. Consequently, despite getting grander public and commercial buildings in the later 19th century, it never had quite the same role as a regional capital as Manchester. Perhaps this explains why the local authorities of Greater Manchester have always found it comparatively easy to work together, and why the situation is rather different in the West Midlands. Not, it should be noted, Greater Birmingham.

So, the question about the Industrial Revolution is not just important in itself, it also tells us a lot about how the two cities — compared and contrasted and recognised as England’s two most important industrial centres since early Victorian times — function today. But back to the question itself. Was Birmingham the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution?

A good comparison might be with computing. Did the technological revolution we’re seeing today begin post-war, at universities and with figures from mathematics like iconic genius Alan Turing and cybernetics guru Norbert Wiener or did it start in the 1980s in Silicon Valley? Depends upon your point of view. For my money, those early impressions in that old science museum on Newhall Street were right – the origins of the Industrial Revolution — conceptual and pragmatic — do lie in Birmingham and its surroundings but, grudgingly, I am forced to confess that it was in Manchester where it all really got going. The sparks may have come from the Midlands, but they landed and caught fire in Lancashire.

Correction: this article contained several inaccuracies when published that have now been corrected.

Comments