By Dan Cave

Earlier this year, almost in passing, a close friend told me a strange tale, about a Killer Whale who lived in Dudley. Whales, in my view, usually inhabit worlds of mystique, far beyond the less glamorous urban sprawl of our West Midlands home. Creatures of the wild, the unknown, the deep. If in captivity: in larger-than-life US theme parks. A Killer Whale? In the Black Country? I had to know more.

Pressing my friend for further info, I was told their dad had worked with animals in the Black Country several decades ago. I got them to bombard him with texts, getting answers, though incomplete ones: the whale had lived in Dudley Zoo, an incredibly popular attraction in the early 1970s, he believed, and had died not long after from an agonising gastric ulcer. The conditions it lived in? “Bad and cruel”, my friend’s father reported.

Fan forums — yes, this whale has fans — online encyclopedias, books and newspaper cuttings, delivered the basics. The Orca, named Cuddles, had first moved to Dudley Zoo from a Yorkshire animal park on 22 May 1971. He was caught off the American West coast in 1968, in the largest ever Killer Whale capture at that point, at the age of two. Torn from the family pod, he was eventually moved to Dudley, at a cost of £30,000 (over £500,000, in today’s money). The pool housing the animal was, by many accounts, just 50 feet long — a tight squeeze for a whale that would grow to 18 feet. As my friend’s father said: “The pool wasn’t big enough for a Killer Whale”. Three years later, on 6 February 1974, Cuddles died.

On paper, it’s an unremarkable story. After all, zoos have a reputation for keeping animals in insufficient habitats — especially in the 1970s. But somehow, a Killer Whale in Dudley doesn’t feel real. What next? A lynx in Slough? A wildebeest in Wycombe? No, to me, Dudley is simply not the sort of place you should find an orca. As I learnt more about Cuddles’ life I became hooked on his story which was a combination of deeply sad and comical. He was at once a performer with a penchant for 10-pint Guinness drinking sessions and kissing bikini-clad women and an aggressive animal who turned on his trainers. In his day, he was a money-spinning star who drew crowds from far and wide — today, he is all but forgotten.

The master showman

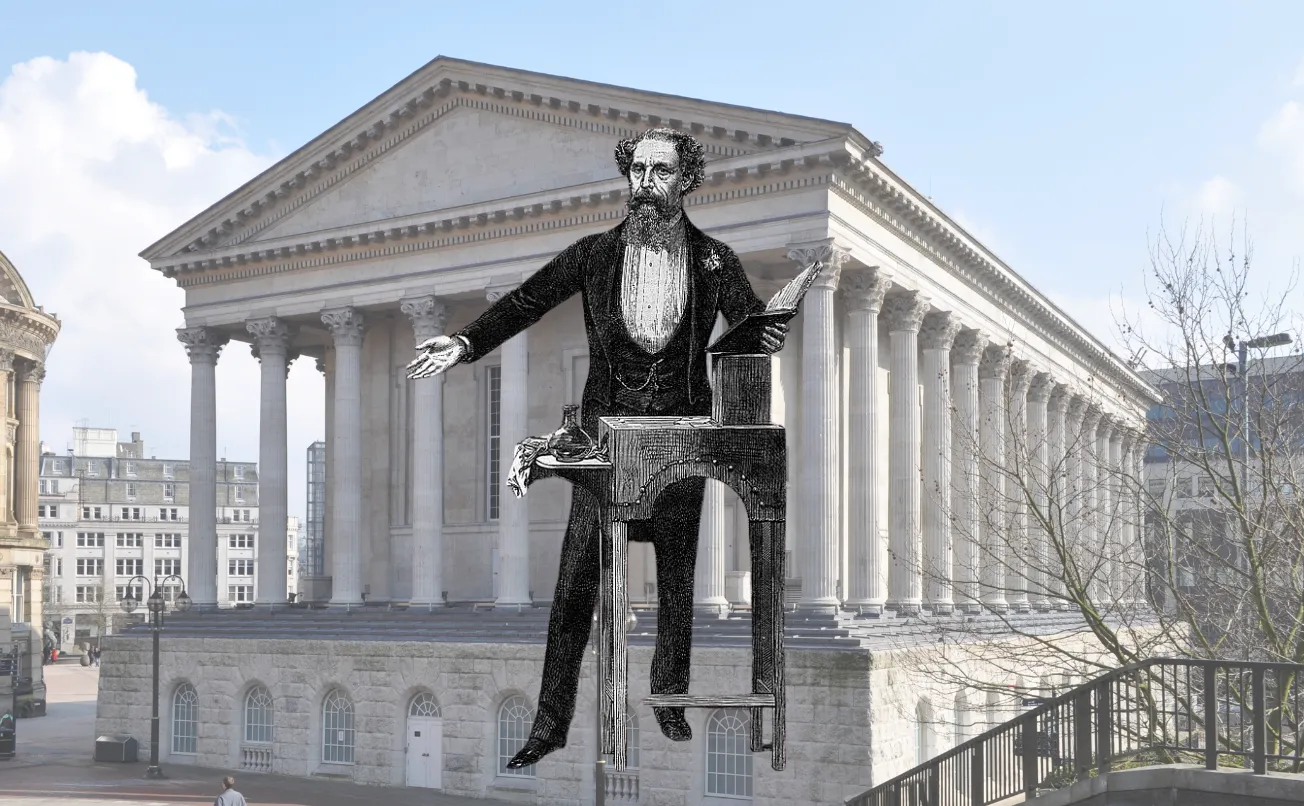

Don Robinson, by various accounts, was an entrepreneur who believed that big could always be made bigger. Born in 1934, by the 50s he’d paid for a patch of Scarborough Beach, renting out trampolines to holidaymakers. Two years later, he had a dozen such sites across the country. It would put a spring in his business-minded step. Robinson would go on to charter the first England to Las Vegas flight and was among the first to invest in Bulgaria after the fall of the Soviet Union. He also once lobbied Nelson Mandela — face-to-face, no less — in an attempt to operate a floating hotel off the coast of South Africa. With a bent for the exotic, he also got into the zoo business.

When David Fowler tracked people down to attest to Robinson’s character, for his 2014 biography Don Robinson: The Story of a High Flier, he was told the man was “shrewd” but also “flamboyant” and “colourful”. As Fowler wrote: “He was the master showman with an unequalled ability to generate publicity.” Indeed, in Robinson’s wrestling promoter days, he once marketed a young Sikh wrestler as ‘The Wild Man of Borneo’ while at a 1973 Christmas dinner, which he’d invited the press to. He claimed then Prime Minister Ted Heath had written to him to apologise for not being there, showing the doubting hacks the apparent Downing Street letterhead.

Though there was a leisure industry whale boom in the UK across the 1960s and 1970s — Yorkshire, Clacton and Windsor all had their own Killer Whales — Dudley Zoo, which was making a financial loss at the time, didn’t have one. Robinson would change that. Already in the zoo business at Flamingo Park Zoo in Yorkshire — where Cuddles originally arrived from Seattle, at first presumed to be female but later found to be male — a 1970 deal would see Robinson take over the running of Dudley Zoo as part of an expanded Scotia Pleasure Parks business. The move would turn the zoo around financially and bring Cuddles down south in 1971.

Perhaps it was only a man like Robinson who could pull this whale-sized move off: the “shrewd” and “flamboyant” businessman who thought the Black Country could do with a whale. It’s a chutzpah that, seemingly, worked. From those who worked at the zoo around this time, I’m told Cuddles was a trick-performing star. By 1973, Don had made the zoo a £280,000 profit (over £5.5m by today’s figures) with the businessman unapologetically telling the press that the whale was at the centre of this upturn in fortunes. ‘CUDDLES THE £20,000 WHALE’ ran an August 1971 Birmingham Mail headline, a few months after the marine mammal had arrived. The zoo shared that, not only would Cuddles perform there, but he would tour at the Munich Beer Festival and across Germany, raking in £2,500 per week while on the road. The same year the whale appeared, the zoo boasted a footfall of over 700,000 visitors, beating a record that had stood for three decades.

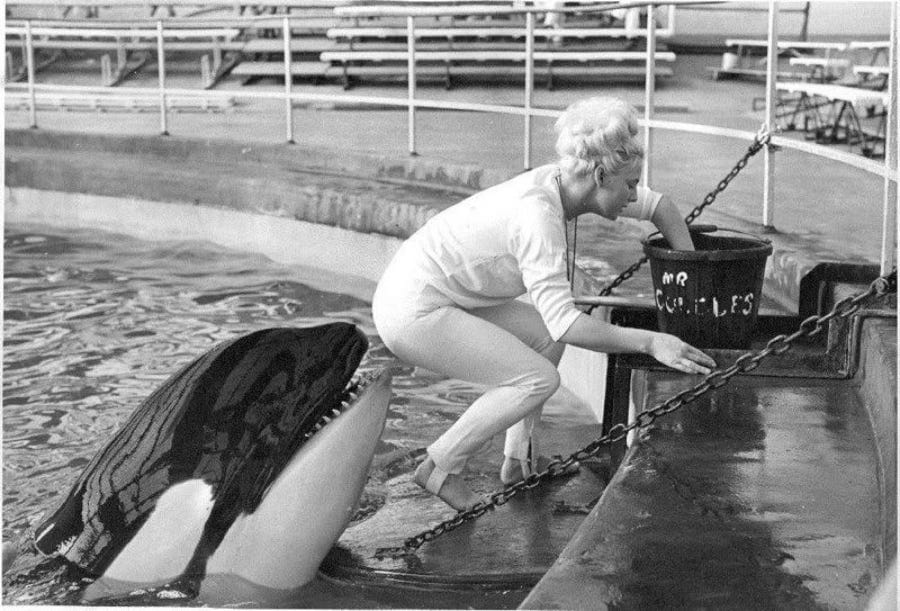

It’s easy to understand why. A 1969 clip from British Pathé captures a sharp-toothed and sleek Cuddles adhering to trainer requests — tricks, pool acrobatics, and even teeth brushing — in exchange for fish. The clip is not from his time at Dudley, but gives a sense of the allure Cuddles had. Like me, crowds were gripped by this creature. But it's not just cute tricks that pulled them in. Cuddles, it was rumoured, had a less acquiescent side. “Dudley Zoo’s new arrival, a killer whale called ‘Cuddles’ didn't live up to his name as he took a quick nip at divers flippers”, was the caption by a small photo in the Express and Star from the day he arrived in historic Worcestershire. Cuddles, the aggressor?

The blood-thirsty orca?

It’s in the Express & Star archives, in Wolverhampton, several miles from Cuddles’ one-time Dudley home, that I get a sense of the whale, how he was portrayed, and his impact. Despite the eventual record football and eye-watering profits, Cuddles' arrival seems to have been a damp squib, at least with the press. The small photo is lost amongst lines on strikes and badly behaved politicians; hardly what Don would’ve wanted for his expensive investment. I’m surprised at the paucity of coverage, although the back pages of old Express and Star editions show Dudley Zoo spending lots on advertisements: from dolphin shows to dinner dances, competing with other zoos for page space.

Indeed, it took Cuddles tearing apart his pool before, separately, going on the blood-spattering attack to cause a splash with local hacks. “WHALE GRABS ZOO OFFICIAL”, is the towering headline that dominates the front page of 8 June 1971 Express & Star. The story tells how Robinson had been dragged to the bottom of Cuddles’ pool by the orca, causing bloody carnage as schoolchildren looked on. It’s an incident that made headlines across the region; the news knocked world-famous Tom Jones and the evolving Pakistan crisis off the top spot.

Cuddles was suddenly hot news. Days later the press gathered at the zoo to watch Robinson — seemingly fine, despite his claims to be in hospital as a result of his injuries — make up with the whale and demonstrate that they were still friends. The zoo made sure to tell reporters that “Cuddles was still performing”. A Killer Whale that lived up to his species name was deathly interesting. From then on, Cuddles was front and centre in the local papers’ bank holiday listings. Soon the zoo was placing quotation marks around the whale’s name to suggest that it was ironic. By the end of the same year, Dudley Zoo’s ad in the Coventry Evening Telegraph enlarged the ‘Killer’ part of ‘Killer Whale’, in a typeface closer to the AC/DC lightning bolt as if to say, “this is one wild animal!” (Subtext: come and see him…if you dare.)

The more the papers covered the whale, the bigger the crowds grew: Cuddles had captured the collective imagination. Back on the fan forum I find Cuddles’ nature a hotly contested topic. “Cuddles was a super aggressive Orca. To the point where it became very dangerous to go near the water's edge,” claimed one forum user. Not everyone is certain, though. John Dineley, a UK wildlife park expert who worked with cetaceans in the 1970s and who responded to a parliamentary inquiry into circus animal conditions, challenged the aggressive depiction of Cuddles. He wrote that the incident with Don only “may” have happened. “Certainly Robinson lived to tell the tale and the zoo milked the story for its free publicity,” he posted.

The tabloid-friendly whale

For the rest of his life Cuddles certainly “stimulated interest”. Sometimes too much. There’s widespread coverage of a zoo break-in in January 1973, during which the whale had spears thrown at him. The previous September, councillors considered building a statue of him in Birmingham’s Manzoni Gardens, although the proposal would never see the light of day. Perhaps the memories of Cuddles “attacking” Robinson made local politicians think this animal would be too extreme for the city.

Or perhaps it was his wild drinking and womanising? Before Cuddles arrived, the Northern Echo showed the whale guzzling a Guinness, part of his ten-pint-a-day habit (the iron-filled drink was supposed to help him recover from anaemia). National coverage in the Sunday Mirror in 1970 snapped the whale with a bikini-clad woman, detailing how he kissed with tongues in a big tabloid spread. Cuddles — you rogue!

For a tabloid-friendly whale, he suffered an inconspicuous end. In the months leading up to his death, multiple articles explained that the zoo had breached planning regulations when they converted Cuddles’ pool — the council said it would have to be rebuilt. Despite reportedly making cash hand over fist, the zoo announced Cuddles would have to be sold. They claimed fans, sad to see the whale go, flooded them with letters. They were in vain. Although orcas can live long lives in the wild, and even marine parks, Cuddles wouldn’t make it to ten years old. Instead, he passed away deep into a cold Black Country winter, 4,500 miles from where he last swam with his pod in open water.

And so that’s the end of this sad tale. In uncovering it, I ventured further down the rabbit hole than I expected, becoming slightly obsessed, I must admit. If I’ve learnt one thing, however, it’s to never trust a flamboyant businessman with a penchant for publicity stunts. That, and that Killer Whales do not, under any circumstances, belong in Dudley.

Comments