By Kate Knowles

Frank Price, the Lord Mayor of Birmingham, was unhappy. It was June 17, 1964, and a BBC documentary had aired the previous night about Caribbean residents living in the city he presided over. In Price’s eyes, the film “failed lamentably as a serious attempt to explain the problems of immigrants”, as he explained to the Birmingham Mail. And yet the film, called The Colony, is remembered and discussed to this day — a sign of how remarkably unconventional it was.

Its director, Philip Donnellan, was a young, plummy-voiced reporter from Surrey who was initially shipped up to Birmingham by the BBC to work in radio, but who found himself inspired by the Free Cinema movement of cheaply made and non-commercial films that turned the camera on working class lives. From 1963, he produced or directed 20 films from Birmingham, many of which elevated marginalised subjects like a chainsmith from Cradley Heath and Irish railway workers in London. The Colony was one of them.

“Let’s find a West Indian who’d do a truthful film about West Indians today,” Donnellan had suggested in a letter to the BBC’s Head of Documentaries Huw Wheldon. Soon he tracked down five people from different parts of the Caribbean who were living here: a teacher, a preacher, a railway signalman, a nurse, and a bus conductor, plus a family of gospel singers. We don’t find out their names until the end credits roll and there is no presenter to spoon-feed us. Instead we are forced to focus on what the subjects are telling us.

Throughout the black and white, hour-long movie, many of the interviews are shot in medium close up — The Singing Stewarts, made up of five brothers and three sisters, are shot very close up, creating an intimate relationship between viewer and subject that is enhanced by their fervent gospel music. You can’t look away. Donnellan weaves in footage of people out and about in Birmingham, often lingering on white women. In his book Second City: Birmingham and the Forging of Modern Britain, the historian Richard Vinen suggests this is to remind the viewer of the prevalent anxiety that if white and black communities live alongside one another, it could result in mixed relationships and ultimately, gene pools. It could also be comparing the black and feminist struggles, as white women were becoming more liberated at the time.

Often the footage and audio is spliced so that we hear from the subjects before we see them. The film opens with a woman speaking in cut glass, received pronunciation. She is talking about children who are not considered eligible for adoption, including “negro and half caste children”, but the image is of Birmingham Town Hall — a reminder of the constant institutional presence in the everyday lives of the subjects. When she says the words “I’m coloured myself” the camera whirls around to show the voice belongs to Pauline Henriques, who was one of the first black actors to appear on British TV and a social worker. From the off, it is clear the film is going to subvert expectations.

“In that era, the voices of different minority groups weren’t being recorded,” Donnellan’s daughter Philippa tells me. “Dad’s take on that was to go into communities, to meet people and to record them and present them on the BBC which was highly unusual at that time. Nobody was doing that.”

The Windrush generation had been called to the so-called mother country to help rebuild a Britain battered and bruised by the Second World War. Donnellan films his subjects at work, foregrounding their roles as cogs in a vast, industrious empire.

But by amplifying their voices, their humanity shines through. They are not dull automatons but eloquent and self-possessed. A stand out scene occurs about a third of the way through the film when a group of the men — the film features mainly men — debate whether or not they should be expected to assimilate into Birmingham culture.

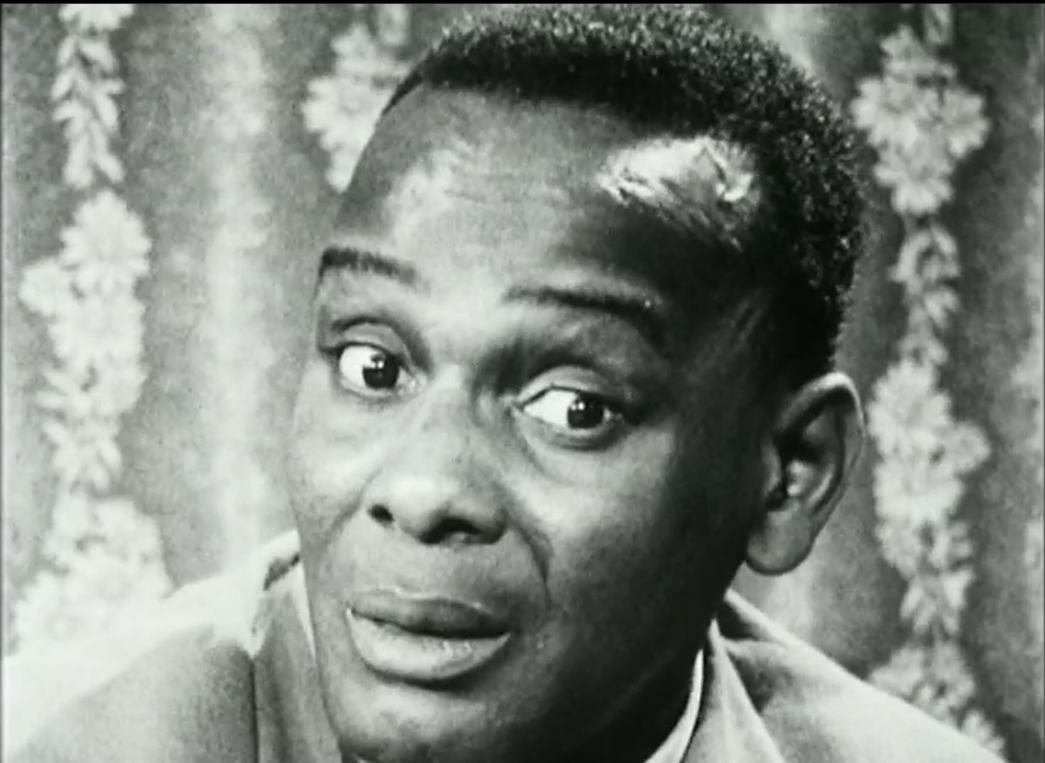

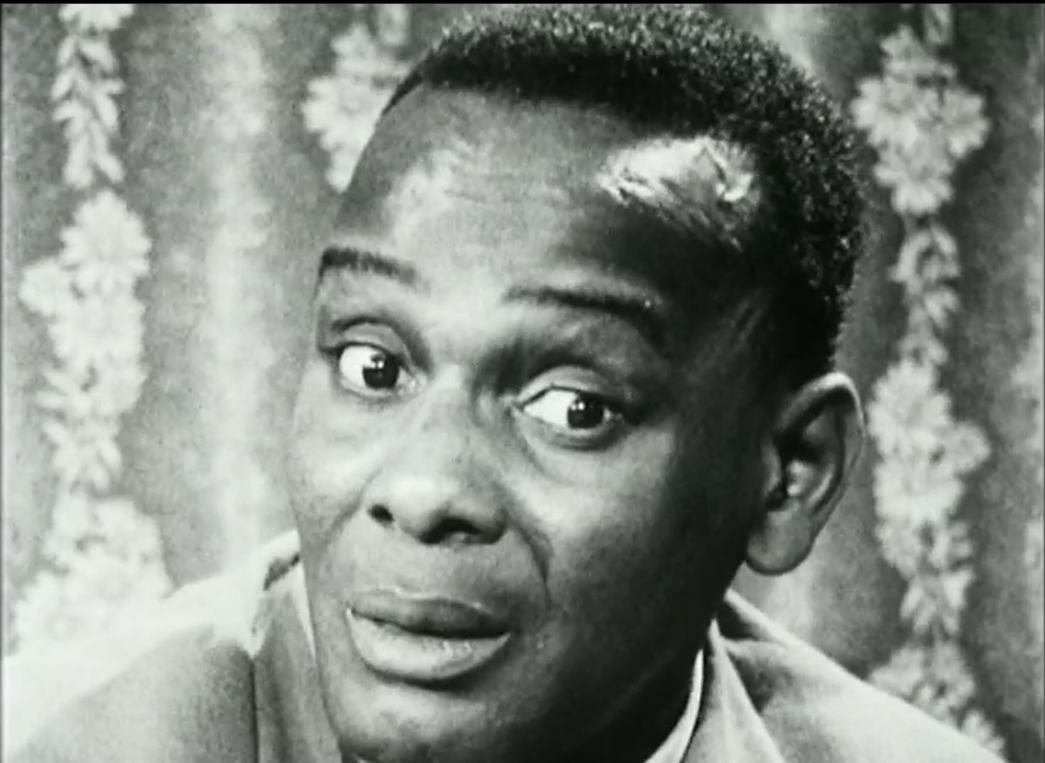

"The star of the show is Stan Crooke,” writes Vinen. “Most of the participants are extraordinarily articulate but Crooke more than any of them has the manner of an educated man." That description might sound patronising, but there’s no doubt that the railway signalman from St Kitts is an absorbing focal point in The Colony. Crooke appears in five different scenes — more than anyone else and it is a sign of his admiration for Crooke that Donnellan ends the film with him speaking. Donnellan would go on to devote an episode of his 1971 series of films about working people, called Where Do I Stand? to Crooke.

Crooke’s daughter, Brontë Garrington, tells me her father and Donellan struck up a fast friendship: “I just remember him being in our house and talking to my father who loved to talk and had a lot to say about a lot of things. Him and Philip just got on really well.” Garrington recalls the struggle her dad faced when he moved to England — not that he spoke about it much. “It was very, very, very difficult. It was a torrid time I think, for black people to put in an appearance,” she says.

Finding a suitable job was tough for Crooke, who came over ahead of his wife and two eldest children. He had received a Victorian-style education in St Kitts and spoke Latin, but was unable to find intellectually stimulating work, closed off as it was to black men. But he enjoyed working in the signal box where he was in charge. “It suited him down to the ground,” says Garrington. “It was perfect for him. And he got to read in between trains.”

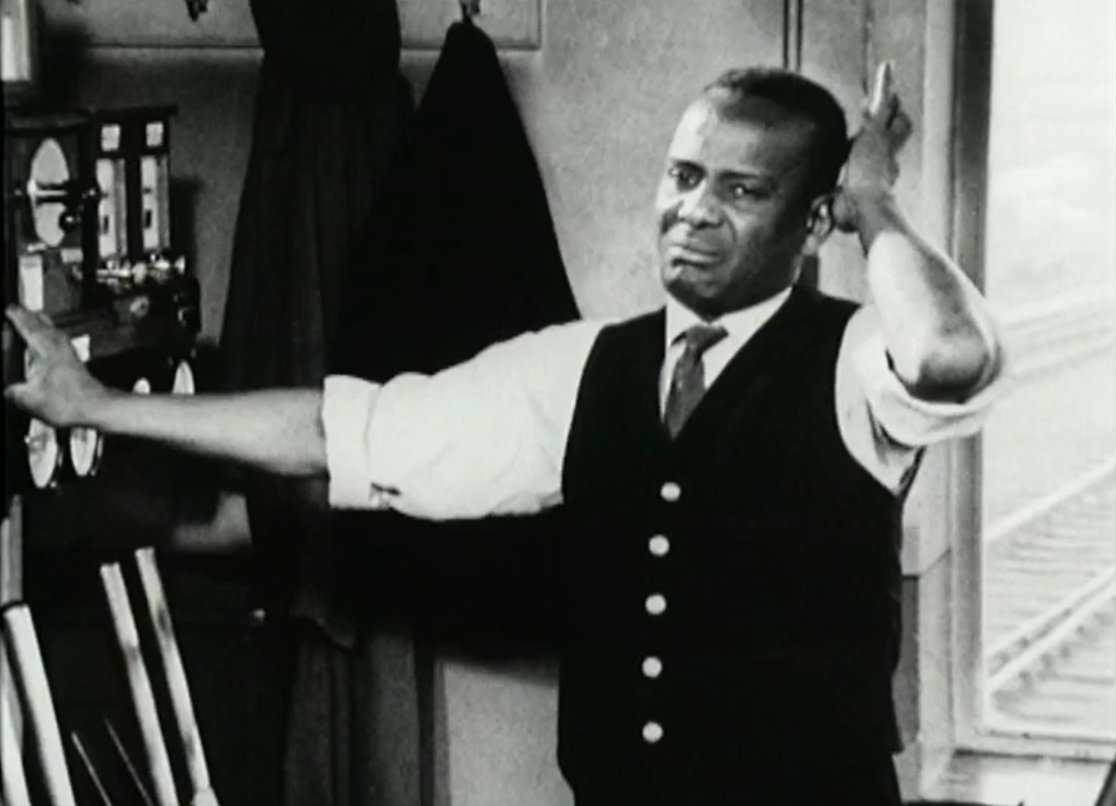

In one scene, Crooke multi-tasks from his signal box, pulling levers while talking about the difficulties of integrating with his white coworkers. Philippa says her father always thought Crooke epitomised the opposite of the stereotype of the uneducated, immigrant worker “coming to take our jobs”. He included that scene, she says, because “he wasn't talking about the job necessarily, but he was talking about his belief system while doing a hugely complicated physical manoeuvre. Dad said that really epitomised his mental brilliance.”

The Colony was made during the third decade of large-scale migration from the Caribbean to England. “By the 1960s, there were increasing anxieties around local resources and work in local populations,” sociologist Dr Paul Campbell tells me. Added to this was explicit national policy to keep white and black communities apart. Caribbean citizens were directed to destitute inner city areas, previously deemed unworthy for locals due to the public health risks. If a black person wanted to get a mortgage, they had to pay a 5% tax that white people were exempt from. They had to wait ten years before they were eligible for social housing.

Smethwick’s Conservative MP Peter Griffiths’ — who was elected the year The Colony aired — deployed the slogan: “If you want a n***** for your neighbour, vote Labour”. Griffiths stoked racial tensions to such an extent that white residents on the racially mixed Marshall Street were lobbying the government to buy up homes on the road and impose Jim Crow-style segregation. The action led to a visit by Malcolm X in 1965, his final international trip before he was assassinated. He told the press he had come, “because I am disturbed by reports that coloured people in Smethwick are being treated badly. I have heard they are being treated as the Jews were under Hitler”. Three years later, Enoch Powell gave his infamous Rivers of Blood speech at a meeting of the Conservative Political Centre in Birmingham.

Even for the time, these events were considered shocking and led to Birmingham becoming “recognised across the world as a cauldron of racial hostility,” as Vinen puts it in his book. There had always been a mix of cultures and ethnicities in Birmingham but this was the first time there was a large number of people here — and in the country — who were not white.

The postwar period had seen a high demand for labour that ended in the 1960s and white communities felt like their jobs and the cultural makeup of their cities were being threatened. Commonwealth citizens were settling down. “Frequently that generation would say ‘this was only supposed to be for five years’ and it became a bit of a running joke,” says Campbell. But naturally, they began to create families or send for their children, just as Stan Crooke had done. “For the first time, Birmingham was becoming a multi-racial city.”

One memorable scene in The Colony demonstrates this turning point. Rather than considering themselves “Jamaican, Barbajan, Kittian, Antiguan”, Crooke and his peers had begun to recognise themselves as black. He describes a stranger waving from the opposite side of the street. “You are positive you do not know him, yet he waves to you. Why?” He muses to the other men. “Because you have one thing in common. One thing which makes him now realise that we can wave to each other and expect to be waved at in return.”

Crooke’s delivery of that line is ambiguous. Written down it has a positive ring to it, a sense of building solidarity in a shared struggle. Certainly, during this febrile period, black communities built up resistance to the hostility they faced. There were local groups largely inspired by the US civil rights movement that set up mutual aid funds to support their communities, as well as national groups like the Antigua and Barbuda National Association.

But the dissolving of different West Indian identities into one category, defined by race rather than nation of birth, was evidently also troubling. As was the common conflation of the entirety of the West Indies with just Jamaica, which Vinen puts down to the fact that Jamaican people made up the majority of Birmingham’s West Indian population — around 19,000 of 25,000 in 1971.

“We grew up very mindful of our parents’ background,” Campbell tells me “There are unique and strong individual island identities, whether it be St Kitts or Jamaica, for example. Some of these islands in the Caribbean are as far away from each other as England is to Russia.”

It’s worth noting that South Asian citizens felt the “cauldron of racial hostility” too. In fact, Vinen suggests that newcomers from Asia were seen “by most white people as the most ‘problematic’ immigrants,” who, unlike those from the Caribbean, were generally not Christian and rarely spoke fluent English. He writes in Second City: “While West Indians were seen as cheerful and sociable, Pakistanis were often described as figures of sinister mystery ‘coming and going like shadows’.” Lord Mayor Frank Price’s quote to The Birmingham Mail implies a similar view. He said: “Last night [the film] showed us only the side of the West Indians, a warm, cheerful and friendly people. In this way, the programme fell short of what it should have been.”

Dr Martin Glynn, a criminologist and author, sees the film as a living testimony of West Indian citizens in Birmingham in the 1960s. But he emphasises that it is important to reflect on to what extent racist attitudes have changed. He says: “The generation that went on to become gang members, to become disaffected and for whom crime becomes a choice, directly inherited the legacy of what that documentary portrayed.”

The making of The Colony itself tells a story. After it was aired, Donnellan fought with higher-ups at the BBC to get them to recognise the importance of depicting what he calls in his unpublished memoirs “the common voice”. He writes that these films “got a rough ride from journalist-controllers who appeared to judge all documentaries in the simplest, most representational terms”. There were times too “when internal politics nullified the work done on the ground.” Later films of his that explored similar themes, like The Irishmen: An Impression of Exile, were shelved with no explanation given.

I grew up in Birmingham but only heard about The Colony when I read Vinen’s book last year. Watching it gave me a powerful new sense of our city’s history and its tangled relationship with newcomers and race. When I had finished it, I wondered: what else could we learn from watching the pensive, unusual films of Philip Donnellan?

Have you seen The Colony? What did you think? You can watch the film on BBC iPlayer — let us know your take in the comments.

Comments