By Kate Knowles and Olivia Lee

As the service at Westminster Abbey was drawing to a close, Archbishop Dr Rowan Williams, in sleepy tones, asked the kneeling congregation to confess their sins. Instead of bowing his head, a man stood up and walked purposefully up the aisle towards the front of the church, arms raised in a gesture of nonviolence.

“Not in my name,” Toyin Agbetu announced. “Not in the name of our ancestors.”

Security guards surrounded him and attempted to hustle him out of a back door. Twice the scrum crashed to the floor, but Agbetu insisted on leaving by the main entrance, on his feet. As they moved away, he pointed to the Queen and shouted, "You, the Queen, should be ashamed!" He then turned his attention to the prime minister. “You should say sorry!” he told Tony Blair, who looked away, awkwardly.

It was 27 March 2007. Until that point, the event — a commemoration of 200 years since the passing of the Slave Trade Act — had gone largely as planned. There had been hymns and prayers, and a lot of focus on William Wilberforce, the 18th century politician, evangelical Christian and philanthropist known for leading the British campaign to abolish slavery. What was absent, however, was any mention of the role that enslaved people had played in their own emancipation. Nor was there any recognition that the 1807 legislation that the event was celebrating did not actually abolish slavery. In fact, it codified into law measures developed by slave owners themselves to make their practice more efficient and profitable — but no less cruel.

Agbetu was no gatecrasher. He’d been invited to the event in his role as the then-leader of Ligali, an organisation he founded in 2000 to challenge the misrepresentation of African people in the British media. Prior to the event, he and other community leaders had been in dialogue with the institutions set to take part in the commemoration. “Don't do it in this way, you're not being respectful,” they had urged them, as Agbetu later explained to The Guardian.

This frustration — that British institutions, including the monarchy, the government, and the church, have not held themselves properly accountable nor accurately portrayed how slavery ended to their citizens and congregations — has only grown since 2007. Last month, 124 people, including Agbetu, gathered in Birmingham for ‘Undoing 2007; Preparing for 2038’, an event organised by Dr Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman to consider how the damage can be repaired. The date they are all looking to is 1 August 2038, the bicentenary of the true abolition of slavery.

Between the passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 and full emancipation in 1838, both Britain and its colonies in the Caribbean saw fervent grassroots anti-slavery activism. In the colonies, a major turning point was the 11-day-long uprising of 1831 led by Samuel Sharpe in Jamaica, after which between 310 and 340 rebels were executed. The rebellion and its aftermath, writes the historian Professor Catherine Hall, “played a crucial part in the recognition in Britain that slavery could not survive as a system”.

In this country, it was not William Wilberforce or any of the prominent male political figures of the time leading the action for an immediate end to slavery. It was a group of women in Birmingham who settled for nothing short of its timely eradication.

‘Unspeakable terrors’

Before the abolition of slavery came a process known as ‘amelioration’. As Dr Claudius Fergus explains to the group gathered at Undoing 2007, this was a policy of sugar plantation management that sought to soften the harshest conditions of slavery, mainly for women and especially for pregnant women and new mothers. Far from altruistic, the short-term objective was to encourage pregnancy and facilitate the safe delivery and survival of newborn babies. The long-term aim was to increase the enslaved population by natural means and reduce the cost of production against the rising cost of importing captive Africans. In short, it was slave breeding.

From the 1770s, amelioration became increasingly associated with the prospect of abolishing the transatlantic slave trade and was ultimately adopted as policy by the British government with the 1807 Slave Trade Act. It became illegal to purchase enslaved people directly from Africa, but those already enslaved were not freed, and the restrictions it imposed on punishments were paltry. “No enslaved person would have celebrated a reduction to 39 strokes maximum, from a slave master’s whip,” says Fergus.

In any case, an unlimited number of strokes could still be used if a court ordered it. They could also condemn a slave to “unspeakable terrors” including the ‘treadmill’, a fast-spinning wheel of widely placed steps that forced the users into endless, exhausting movement. It was “one of the most excruciating forms of judicial punishment,” says Fergus. “Let me state emphatically that amelioration was still chattel slavery.” This was allowed under the Act that would be celebrated 200 years later.

Why did the British government pursue amelioration? During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, uprisings of enslaved people erupted across the Caribbean, posing a threat to the bloodthirsty economy overseen by white plantation owners. In 1760-61, the largest rebellion of enslaved peoples in the Americas prior to the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804) broke out in Jamaica, known as Tacky’s Revolt. ‘Dr Fergus argues that British fear of such insurrections provided the rationale for abolition.

However, the ruling class’s financial interest in maintaining free labour in the colonies was so great that ending slavery was not on the table. Moderate ‘reforms’, which from 1823 onwards reforming activists called “gradual abolition”, were the only palatable option. Or so the male-dominated anti-slavery organisations (including the London Anti-Slavery Society led by William Wilberforce and Thomas Clarkson) claimed — wary of upsetting members of their own class, many of whom were enslavers themselves. Outraged by this half-measure, a group of women in Birmingham broke away from the mainstream movement to fight for an immediate end to slavery. They were spurred on by social critic and radical activist Elizabeth Heyrick.’

The Birmingham Female Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves

Heyrick, a Quaker born in Leicester in 1769, has largely remained hidden in the shadows of Birmingham's anti-slavery movement. Her elusive legacy is accentuated by the fact that the only surviving image of her is a black-and-white silhouette. A shadowed side profile, masking the expression of her face, is distinguished by a white laced bonnet, tightly pulled under her chin with a frilly strap. What the silhouette cannot reveal about Elizabeth Heyrick's character, her bold, striking and persuasive rhetoric vividly brings to life.

Gradual abolition “is the very master-piece of satanic policy”, she declared in 1824 in an explosive pamphlet that would go on to dramatically alter the course of the British anti-slavery movement. The 10,000-word text was the first to publicly attack what had been the mainstream abolitionist stance of the time. Gradual emancipation, she argued, was far “too accommodating” — “polite”, even — in the face of the abhorrent “injustice and cruelty of slavery”.

Her pamphlet spurred a new wave of activism from women across the country. Finding themselves marginalised from mainstream male-dominated anti-slavery groups, they began to organise independently. In 1825, Heyrick and fellow abolitionists Lucy Townsend, Mary Lloyd and Sophia Sturge (Joseph Sturge, her brother, is better known than the women) founded the Birmingham Female Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves. It would go on to become one of the most important active abolitionist groups in the 19th century. That said, the women were not without their faults. Although Heyrick demanded immediate abolition from 1824, the society was in favour of a gradual approach until 1830.

Central to the society's objective was raising funds and support for the relief of enslaved people — particularly enslaved women, such as Mary Prince. Born in Bermuda in 1788, Prince was a prominent force in the abolitionist movement. After gaining her freedom upon her arrival to England in 1828, she was supported in writing the first-ever female-written slave narrative by Thomas Pringle.

The book, titled The History of Mary Prince, documented Mary’s horrific and brutal experience of the slave trade and had a profound impact on the anti-slavery movement, selling out three print runs in its first year. The Birmingham Female Society helped fund circulation of this book — but it should be said, only after they had received confirmation that its contents were true from a group of white women in London who had conducted invasive inspections of Prince’s body to check for whip marks. The book itself is problematic because Prince could not read or write — her story was written for her. Ifemu Omari Webber points out that it functions as a piece of anti-slavery propaganda for a white audience.

The Birmingham Females Society adopted an array of strategies that allowed ordinary women to participate in the campaign against slavery. Most famously, the society launched a slave-grown sugar boycott, which aimed to leverage women's domestic influence and role in purchasing household goods. The boycott was so successful that within a year of its beginning, close to 25% of Birmingham’s population had moved to free-grown sugar.

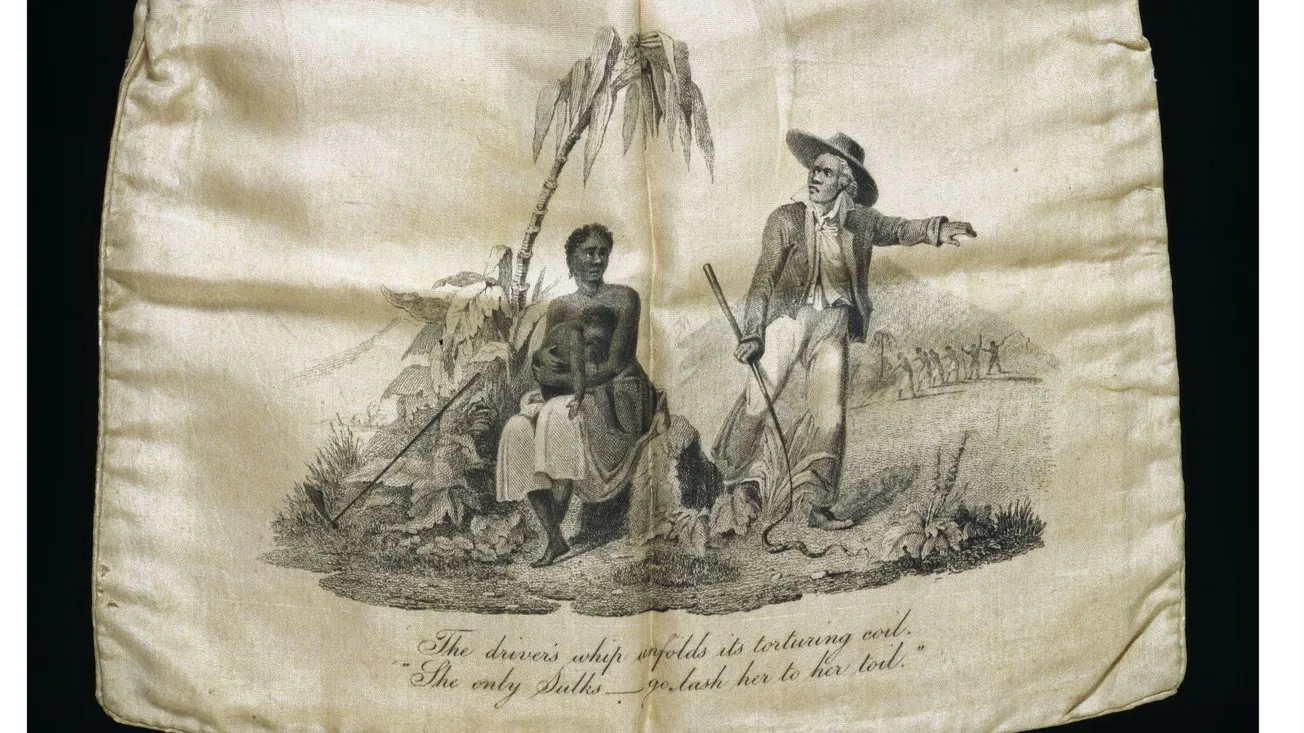

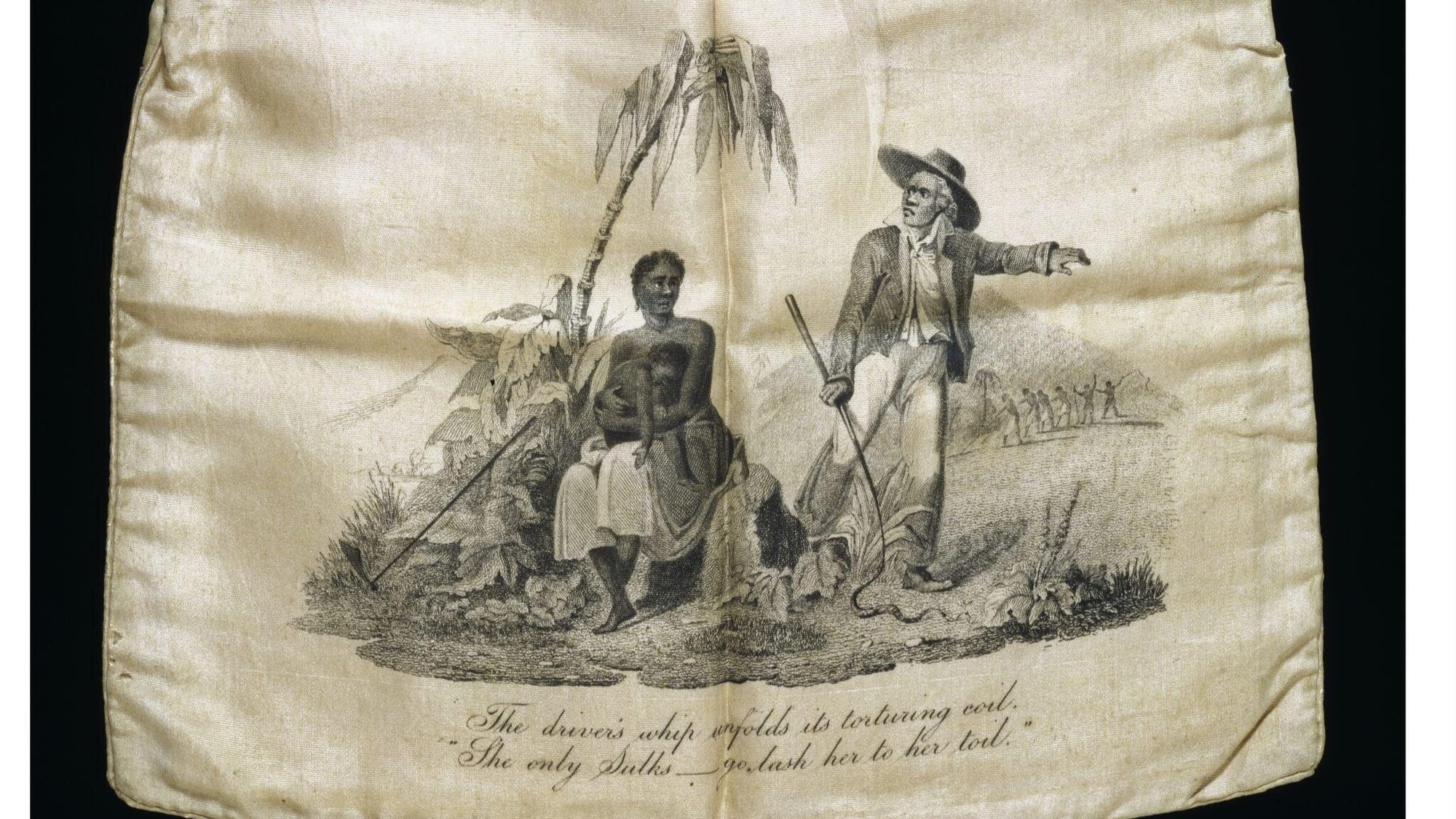

To raise funds for their campaign, the society produced and sold work bags decorated with abolitionist emblems, and filled with anti-slavery pamphlets and literature. One of the bags portrays a female slave cradling a child in her arms. Her hand is raised to her forehead as if in a bout of despair. On the reserve is a poem describing a woman in captivity weeping over her sick child. A similar work bag is on display at the V&A Museum in London.

The presence of women in the movement was generally objected to by male abolitionists. William Wilberforce went so far as to ban his followers from speaking at women's anti-slavery organisations. Yet they were soon forced to heel to the women’s growing influence. In 1830, Elizabeth Heyrick and the Birmingham Female Society threatened to withdraw their funding from the London Anti-Slavery Society if it did not adopt a stance of immediatism. Given that Birmingham women provided one-fifth of their total funds, the organisation quickly buckled.

The London Anti-Slavery Society agreed to remove the words “mitigation and gradual abolition" from its title. There was still a long road ahead, however. The London Anti-Slavery Society continued to be committed to amelioration and spent much of the 1830s defending it. In 1833, legislation brought about apprenticeships — a form of amelioration that was denounced by the Birmingham Female Society. Finally, in 1838, full emancipation was won.

The ‘unholy scramble for souls’

It was the missionary Reverand Benjamin Dexter who gave New Birmingham its name, in honour of his friend, Joseph Sturge. Dexter was the cousin of William Knibb, a missionary who acquired land across Jamaica for former enslaved people to live on — part of a campaign known as the Free Village movement. While benevolent in some ways, the missionaries' relationship with formerly enslaved people was complicated. Their settlements always included a church and freedom came with the proviso that the villagers converted to whichever denomination their founder was part of.

After the uprising of 1831, William Knibb and Thomas Burchell travelled to England to drum up support for the right to education for enslaved people and their descendants. Parliament established the Negro Education Grant: £30k a year for anyone who wanted to set up a school in the Caribbean between 1835-45. The initiative failed. The missionaries descended into factionalism, using the money to instead build churches to compete with other denominations.

The schools that were built provided a comprehensive education for the children of missionaries and mulattoes only. African children learned reading, writing and arithmetic in church basements using only the Bible. The missionaries believed that Africans were morally and academically incapable of such advances and should not be encouraged to rise above their God-given station in life. Reverend Dr Doreen Morrison explains that even the British colonial office accused the missionaries of misappropriating the funds in their “unholy scramble for souls”.

Today, New Birmingham is known as ‘The Alps’, another name that was likely given to it by European settlers because its mountainous terrain reminded them of the Alpine countries. When Knibbs founded it, coffee, sugar cane, bananas, cassavas, oranges, mangos and breadfruit grew there. However, due to a lack of infrastructure, the diversity of produce has dwindled.

Property developers and mining companies have expressed an interest in the land, and the residents have organised to protect it. The Alps Community Development Committee and the Alps Sisters Movement want to refurbish the buildings so they can install a museum and comfortably welcome visitors, which would be good for the local economy. The farmers want to build a processing plant and plant fruit trees to protect the endangered species and their ancestors’ graves from development. One of the sisters explains in a video: “All those graves would be dug up and thrown away and there would be no history for us to pass down.” In another, a man says England has “unfinished work” here. “I would like to know when are they going to pay us for what they done to our families.”

The most vital calls are for education and the end of illiteracy — one of the points on the 10 Point Plan for Reparatory Justice published by CARICOM (a group of 20 countries in the Caribbean). It speaks to the empty promises of the English after slavery came to an end.

But there is a need for education in England, too. Dr Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman and the movement are calling for a ‘Curriculum about Birmingham’, which would include well-evidenced histories of the distinction between abolition and amelioration. Among other things, they also want apologies for amelioration and apprenticeships which could provide reparatory justice, both for the people of Birmingham and former New Birmingham.

At Undoing 2007, Toyin Agbetu is the first guest speaker of the day. His message is as forthright as it was at Westminster Abbey, but this is a receptive audience. “A little over 200 years ago — barely two generations — was not a one-off in history,” he says, “but the lighting of a fuse of a chain reaction still yet to be fully realised.”

You can read more about Undoing 2007 here.

You can find key texts by Professor Catherine Hall here and Dr Claudius Fergus here.

We have made several corrections to this article:

- We have corrected the National Anti-Slavery Society to refer to the London Anti-Slavery Society (full title: The Society for the Mitigation and Gradual Abolition of Slavery).

- We have corrected the name of the Birmingham Female Society for the Relief of Negro Slaves, which we previously called the Birmingham Ladies Society for the […].

- While Heyrick argued for immediate abolition from 1824, the Birmingham Female Society did not promote this position until 1830.

- The Birmingham Female Society helped to fund the circulation of Mary Prince’s book, not its production. They only did so after white activists in London had taken it upon themselves to corroborate Prince’s claims by conducting invasive searches of her body.

- Reverand Dexter Knibb has been corrected to Reverand Benjamin Dexter.

Comments