By Danny Thompson

My mum is on end of life care, visited regularly by nurses from a hospice. Years of chronic lung conditions have left her unable to breathe unaided. Wires go in and out of her, while machines bestowing artificial breath whir and chirrup on a constant loop. She’s 62.

“If you were a dog, mum, they’d put you down,” I joke. We have a dark sense of humour in my family.

Mum’s health has been bad for years, but has taken a steep decline in the last 18 months. She’d always worked tirelessly to provide for her four children, often as a single parent. She would work nights and double shifts to make sure we always enjoyed holidays, had presents under the tree at Christmas, and generally never went without.

She married my step-dad when I was 13. They always harboured dreams of retiring to Spain, which came true in 2012. But her health worsened and her need to see specialists on a regular basis meant living there was no longer sustainable. They permanently swapped their apartment in southern Spain for a Coventry terrace a few years ago.

“It was growing up by that bloody factory,” she’d said numerous times through the months and years, often fighting for breath as she did.

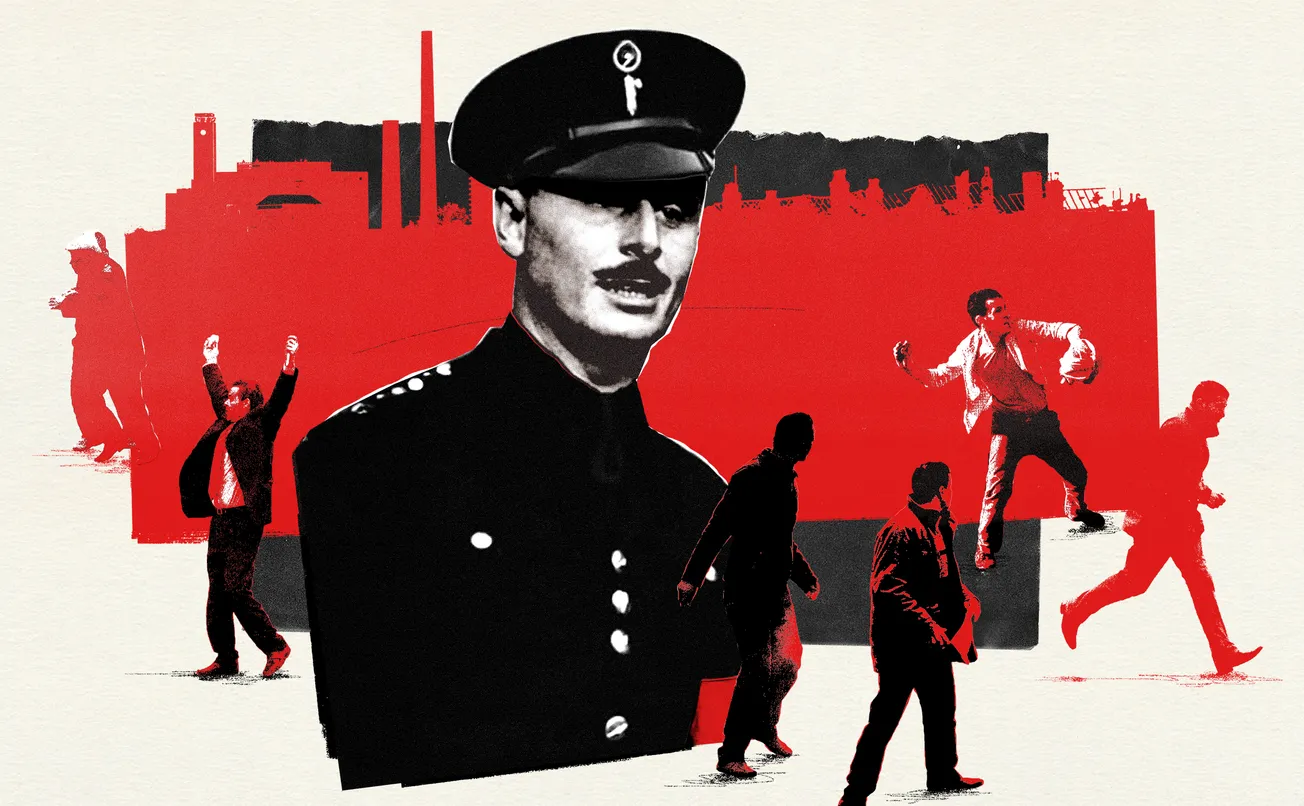

The factory she is talking about belonged to Courtaulds, a textiles and chemicals heavyweight that was one of Coventry’s leading employers for almost an entire century until a 1998 merger with a competitor led to the closure of its local sites. Courtaulds had several different factories, as well as its headquarters, dotted around the northern part of the city.

But the thing everyone knows is the tower. A 50-metre flume-like chimney — the tallest of its kind in the country — piercing the grey Coventry skies with smoke billowing out of the top. Little Heath Primary School, which my mum attended, was at the foot of the chimney.

Mum’s parents — my nana and grandad — were both born in Liverpool. In 1964, the family and their four children (of which mum, aged three, was youngest) moved to the West Midlands for work. Coventry was an industrial city that boomed economically and demographically in the late 19th century and well into the 20th due to its bicycle and, later, car industries. It was grey, in more ways than one. Scores of factories blanketed the city and its skies in an omnipresent industrial smog.

Coventry’s factories made it a prime target for the Luftwaffe during World War Two, and the city was decimated in the Blitz of November 1940. By the early 1960s, many of the open wounds inflicted by Hitler’s bombs had healed to scars, but the mediaeval city, once famous for its quaint silk and watchmaking trades, was now a modern and brutalist industrial enclave.

But all this industry also meant there were plenty of jobs available. Mum’s family was just one of the tens of thousands who moved to the city from all over the British Isles, as well as the Commonwealth and other former colonised countries, at that time. In fact, such is Coventry’s status as a migrant city, you’ll struggle to find a modern Coventrian who can trace family back more than a generation or two before finding a relative who came here to work.

My grandad worked two jobs to provide, while my nana had a further two children, six in total. They lived in the Little Heath area of the city, a smaller part of the wider and more well-known Foleshill district. My grandad didn’t come for an industrial job (he worked for the council as a rent collector) but the city’s industrial past and present would shape the future of his family’s life. By the 1970s, mum’s teenage years saw her suffering with fairly innocuous, and at most inconvenient, issues relating to a dulling of taste and smell.

“I always struggled with my senses,” she says. “It was worse around smokers. If someone lit up a cigarette, the smoke would cause me to cough and splutter and I wouldn’t be able to smell anything. If I was eating and someone nearby was smoking, I wouldn’t be able to taste the meal.”

My mum’s issues with her breathing and senses continued, and then worsened considerably, in her late-40s. She was diagnosed in 2009 with hypersensitivity pneumonitis, which according to the British Lung Foundation, is a condition in which “your lungs develop an immune response to something you breathe in which results in inflammation of the lung tissue”. She’d never thought much about the niggling issues with her senses, but such a life-limiting lung condition diagnosis made her start re-evaluating not just her own health, but that of those around her.

Yes, some people fall ill young. Some have chronic conditions that limit life expectancy as well as quality of life. Standalone cases aren’t particularly rare. But how rare is it for more than one sibling in a family with six children to have such conditions? What about three? What about four? Five?

“My baby brother David was always a sickly child, allergic to all manner of things including milk which in those days as a baby made it difficult,” mum says. “But as he was the youngest of six and his health was always poor, we all doted on him.” But my uncle Dave’s fragility remained beyond infancy, and he developed fibrosis of the lungs, which left them inexplicably scarred and inflamed. He died tragically young, aged just 22. The causes of this condition are unknown, though some specialists believe it can be caused by breathing in something harmful.

One of mum’s older sisters also lives with a chronic condition, sarcoidosis, which affects her lungs and breathing. The NHS believe it’s possible that environmental factors play a part in the condition. This is three of six siblings, none of whom were smokers, with life-limiting lung conditions. Another aunt suffers with fibromyalgia and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis, better known as ME, or Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Another has psoriasis.

The cause of these three conditions is officially unknown. However, sarcoidosis and psoriasis are both auto-immune conditions. According to the British Medical Journal, “long term exposure to [environmental] air pollution is linked to a heightened risk of autoimmune disease”.

“Through the years I've heard of so many people, neighbours, classmates that have had lung issues — so many of them were told it was emphysema caused by smoking, but most of them never smoked in their lives,” mum says.

How likely is it that five out of six siblings all suffer with disabilities or life-impacting health issues? This isn’t a family raised in neglect or malnourishment. Like many working class families in the 1960s and ‘70s (particularly those with multiple children, as was more common then), money was tight, but both parents worked when they were able to and there was always food on the table. So what else could lead to such a pattern of ill-health — one that, anecdotally, is not unique in the area?

“Opposite my primary school was the tall, skinny Courtaulds chimney,” mum says. “I don’t remember stuff coming out of it specifically, but there was a constant smell. It was that strong you could taste it. It was almost vinegary, acidic. It made your eyes sting.”

Courtaulds had existed since the 1700s, but came to Coventry in 1904. It specialised largely in textiles and chemicals, and later dominated the man-made fibre industry. It employed thousands of people in Coventry, as well as in other sites across the UK and in North America.

Here in Coventry, it’s generally looked back upon fondly. It paid well, had sports clubs, events and invested in the community. Older Facebook users fill Coventry memory Facebook groups with rose-tinted reminiscences about the company. But among some people, there's a noxious undercurrent to the nostalgia. Courtaulds’ extensive work with chemicals meant that the consumed materials had to go somewhere.

Carbon disulfide (also spelled ‘disulphide’), a flammable liquid discovered in the early 1800s, is capable of dissolving just about any item. This solvent was integral as the vulcanisation agent in the production of rubber, used to make tires that would transform the world of transport. But by the early 20th century, it was discovered carbon disulfide could also make rayon, sometimes known as viscose. You might not recognise those names, but there is a good chance you own clothing which contains it. Rayon was a man-made alternative to silk, and it completely transformed the worldwide textiles industry. Courtaulds had rights to produce rayon, and did so when they came to Coventry.

But there was one problem. Carbon disulfide — this extremely valuable substance making some people very, very rich — was in fact very, very toxic. According to a 2016 Incident Management report from Public Health England, carbon disulfide is a toxic substance, which should “avoid release to the environment”. Substantial releases would require the Environment Agency to be alerted. The same report also states the substance “causes damage to organs through prolonged or repeated exposure” and is “suspected of damaging the unborn child” if exposed to those expecting.

In the preceding decades, it was suspected within medical circles that carbon disulfide was causing an array of alarming issues in those it came into contact with: insanity, sight issues, and lots in between. The findings around what carbon disulfide could do when emitted into the atmosphere threatened the Courtaulds empire. According to Paul Blanc, an American professor who wrote a book called Fake Silk about the dangers of rayon production, the company had known about this in the 1960s and tried to stop these findings being published.

Keith Browning worked in the spinning room at the Little Heath Courtaulds site in the 1980s. “It was absolutely filthy,” he says. “It stank all the time, and when you’d leave it would stick to your clothes and get in your pores. I did it for a few months, but it wasn’t for me. Eventually I found something that suited me better.” One resident, who asked not to be named, tells me her father worked at the same site for decades and developed a cough he could never shake. Sadly, he’s no longer alive to give further information. My own paternal grandfather worked in the factory, as did my dad and his two brothers. It seems ironic they may have inadvertently been contributing to a lifetime of ill-health.

These problems weren’t restricted to Coventry. Wherever Courtaulds has had factories, they’ve also had legal issues. In Axis, Alabama, they had another factory where carbon disulfide was used to make rayon. In the 1990s, they were sued for $1 million by the Long family, who reared horses locally. According to the legal documents related to the case, Mr Long noticed a “smell,” that “caused a burning sensation in his nose and throat”. Later the Longs’ horses began to fall ill, losing weight and struggling to breathe. Two of them died, according to expert testimonies, “as a result of exposure to a toxic substance”.

One vet claimed the death of the horses was directly caused by substances Courtaulds used in their factory. The Longs lived and kept their animals on land three or four miles from the factory. If such damage can be done over that distance, imagine what it could have done to a generation of school children who took their fledgling steps in education at the foot of a chimney belching toxic waste above their heads. Imagine what it could have done to an already sickly baby, like my uncle Dave, who lived a few hundred yards down the road.

The Longs’ court case saw Courtaulds accused of running their plant “negligently”. A search through past editions of the Coventry Telegraph suggests that this laissez-faire approach might have been a company-wide issue. In April 1971, Courtaulds admitted to polluting the River Anker in Nuneaton, near Coventry, though they only owned up when the evidence against them was undeniable. In February 1985, a fire at the Little Heath factory in Coventry was caused by a leak of carbon disulfide.

The same year, a tipping site on the edge of the city, used by Courtaulds since the 1920s to dump industrial waste, was subject to a public inquiry, where a council official claimed the site was known to be a fire hotspot due to lingering flammable carbon disulfide. It was alleged in the story that explosions were heard, and on one occasion, a fire kept reigniting itself every time firefighters thought they’d extinguished it.

In 1981, Courtaulds was caught up in a scandal when an industrial workers’ union claimed employees at one of the company’s factories in Wales died due to exposure to carbon disulfide via the production of rayon. Three were alleged to have been killed in a short space of time. Courtaulds defended their safety measures and denied any wrongdoing. But this wasn’t the first occasion Courtaulds production methods had been subject to such claims. In November 1968, the Coventry Telegraph reported on a British Medical Journal study which found “there was an increased risk of coronary heart disease among workers in the viscose rayon industry”.

By the 1980s, the textiles industries were looking east, particularly to East Asia, for production. Courtaulds eventually merged with competitor Akzo Nobel (we approached Akzo Nobel to respond to this story but they did not reply). As the company moved away from Coventry, the Courtaulds name became all but defunct. The chimney that dominated the Coventry skyline for 100 years was finally demolished in 2010, and housing, flats, and office suites now take up most former Courtaulds sites in Coventry.

And yet, the company’s legacy lingers. “I think living and going to school beneath that chimney ruined my life,” my mum tells me through wheezing breaths. “I’m 62, and I’ve not been able to be a hands-on grandparent. I won’t get to watch all my grandchildren grow and turn into adults. I think Courtaulds robbed me of that privilege.”

One can’t say for certain whether the chronic ill-health of my family and others in the area was caused by pollution from Courtaulds. Some things, though, are undeniable. First, at least three members of my family suffered lung conditions believed to be linked to pollution breathed in through the atmosphere. Second, the family lived beneath a factory which is known to work with a toxic substance recognised to be dangerous and volatile throughout its history. Third, the company which owns this factory has a history of polluting the local environment and possibly causing danger to employees across sites in different countries, including Flintshire in Wales, Carrickfergus in Northern Ireland, and Axis, Alabama in the United States. Fourth, that company has an apparent history of denying wrongdoing until confronted with incontrovertible evidence.

We will probably never have definitive evidence. But let me end by saying this: I think of Courtaulds as I watch my mum, always a strong, robust, and matriarchal figure to those around her, whither away before me as she fights for every breath.

Comments