Dear readers, for today’s weekend read, we have a fantastic piece by Ian Burrell, who began his career as a reporter at the Birmingham Post & Mail. He later worked for the Sunday Times and The Independent and is now one of the country’s leading media commentators, writing regular columns for the i paper. We asked him to look back at his time in Birmingham — and to reflect on the dramatic changes in an industry that once boomed in the West Midlands.

The lost world of West Midlands media

Our region used to have some of the most successful newspapers in the land. What happened?

On a shelf beside my desk stands a miniature toy van with distinctive blue livery and the name “Birmingham Mail” inscribed on its side. “The Great Evening Paper”, reads the proud slogan adorned to the van’s doors, with no irony intended.

There was a time, not so long ago, when the Mail could make such a claim and nobody would argue. With daily sales touching 375,000, and serving a readership that stretched from Stafford to Stratford-upon-Avon, the paper was a fixture of Midlands life. “At one stage we overtook the London Evening Standard in circulation,” recalls Ian Mean, a legendary news editor of the early 1980s.

Every weekday afternoon, the Mail’s vans would begin queuing along Printing House Street, behind the iconic Birmingham Post & Mail building in Colmore Circus. Their destinations included all postcode districts with a ‘B’ prefix, and more distant parts of the Black Country, Warwickshire and Worcestershire. To hasten their journeys, the drivers had a petrol pump on site.

Their inky-smelling cargo came fresh off the hot metal presses that thundered and whirred at the base of the building. Upstairs, a layer of tobacco smoke hung in the air above a seething newsroom the size of half a football pitch. It was referred to as the “Goldfish Bowl”, because company executives could peer down on journalists through a glass balustrade surrounding an atrium above, but it was more Atlantis than fish tank. Entire newspaper staffs colonised sections of the floor: the Mail to the left, the more upmarket morning Birmingham Post to the right. The Midlands-wide Sunday Mercury was at one end, and Saturday’s Sports Argus at the other.

Stories were written against the din of clattering typewriters and constant shouting, as the various desks — news editors, sub-editors, picture editors, photographers, copy-takers — went about their respective tasks. Litter bin fires would break out from casually-discarded cigarette butts. There were fist fights on the newsroom floor. Hard-drinking reporters formed the “10.31 Club”, a reference to their first pint of the day at the Queen’s Head in Steelhouse Lane. They had a club tie.

News was not as immediate as it is now, when a finger on a phone app delivers instantaneous updates. But the raw energy of the production process was undeniable. Down in Printing House Street, newspaper sellers would snatch up bundles of the City final, and hurry back to their kiosks quicker than any van could traverse the afternoon traffic.

The papers were a cash cow. Thursday’s Mail was the jobs edition, adding up to 50 pages of ads. One memorable Thursday, the managing editor was able to declare that the ad pages were simply full. No more money could be accepted.

The Mail was compiled by more than 200 journalists, many operating from a network of district offices that stretched from Walsall to Solihull. These were the golden days of West Midlands print media, when the Mail and its old Wolverhampton-based rival, the Express & Star, would shift well over half a million copies a day. And a high-quality free paper, the Daily News, was distributed to 300,000 homes, four days a week.

Today, the Mail — operating in a metropolis of more than one million people — has a circulation of just 5,074. That reflects the demise of print media, a global trend. But Birmingham’s paper has declined worse than others. Titles in smaller places, such as Dundee, Stoke-on-Trent, Ipswich and Leicester, still sell considerably more. Aberdeen’s Press & Journal has a daily sale of 24,852.

“The influence of a daily newspaper ought to be one of the heartbeats of a city and in Birmingham it has not been the case for many years,” says Steve Dyson, who was raised in West Heath and edited the Mail bravely over five tough years until 2010.

Where did Birmingham go wrong? And how might things be made better, so that the people of the West Midlands are abundantly supplied with the trusted and authentic information that shapes civic and regional identity and makes the rest of Britain take note?

Birmingham’s thirst for news runs deep. During the early industrialisation of the 18th century, there was a need for media to meet the intellectual curiosity of a fast-expanding city. Thomas Aris, a printer, founded the Birmingham Gazette in 1741 and it became one of Britain’s leading provincial titles, employing a London correspondent.

The Birmingham Daily Post launched in 1857 and identified with the city’s radical politics. It gave a platform to the great Birmingham MP John Bright. The Post merged with the Gazette in 1956. It became the voice of West Midlands business and was highly-respected within the arts. Its book reviews were prized by publishers for cover blurbs. Today, the Post is a weekly with a circulation of barely 1,000.

Another once-popular daily, the Birmingham Evening Despatch, was featured in an early Peaky Blinders episode. It flourished in the early 20th century before being absorbed by the Mail.

The disintegration of Birmingham’s independent media is a consequence of many things. Technological change played a major part. So did the city’s shifting demographics. Successive owners failed to respond to these challenges and made more mistakes besides.

These problems were hard to discern when I pitched up at Colmore Circus in 1987. The towering Post & Mail building, designed in New York style with its own penthouse, was barely 20 years old and a fixture of the city skyline alongside Lloyd House, West Midlands Police HQ.

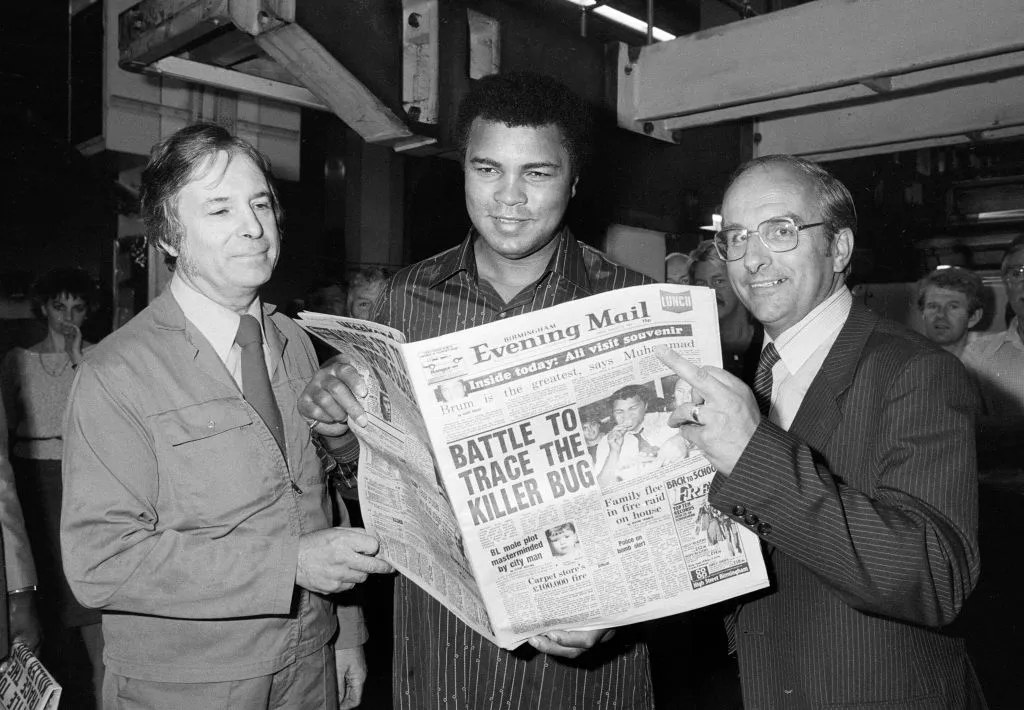

It was the Eighties. The newsroom coffee machine emitted a foul and molten stew that dribbled into a white plastic cup. The toilet paper had a shiny, non-absorbent texture that bordered on an infringement of human rights. But the newspapers had switched to “new technology” (massive computers with plain green text) and brimmed with journalistic talent that would go onto senior roles at the BBC, ITV and Fleet Street titles from the Sun to the Guardian. Even Muhammad Ali walked that floor during a visit to the city, following an invite from Mean, who covered an Ali title fight in Las Vegas while reporting the 1980 US elections. The Mail looked out to the world — I was sent to America to report on its crack cocaine crisis.

The picture library was a social history treasure trove, housing thousands of manila envelopes stuffed with prints of such events as Malcolm X’s visit to Smethwick in 1965 and the St Andrew’s riot of 1985. At one end of the newsroom, a cricket-type scoreboard recorded the Mail’s latest circulation, still in excess of 200,000. Confidence was reflected in the paper’s campaigning zeal. Then-editor Ian Dowell would hire a double decker “Battle Bus” and take it down to London to champion “Big-hearted Brummies”, as the paper often referred to its readers.

That campaigning verve reached a high point with the closure of the Longbridge MG Rover plant in 2005, after 100 years of car-making on the site. The Mail printed T-shirts replicating its angry headline — “Stabbed in the Back” — and sold 12,000 copies of the paper to those participating in the 80,000-strong March for Rover. “That showed the power of local press,” says Chris Morley, the Mail industrial correspondent at the time. “There was real clout and print campaigns were effective in changing the tone politically.”

But the Mail’s notion of “Big-hearted Brummies” did not extend to all sections of the city’s changing population. In Handsworth, smarting from the riots of 1981 and 1985, the paper was viewed with deep suspicion — with reason. I recall that one journalist kept a Rastafarian-style wig under his desk as a party piece. Black or brown faces rarely made the papers, unless accompanying a sport or crime story. When covering a fatal traffic accident as a cub reporter for the Post, I was told not to follow usual procedures and request a photo of the child victim. The tragedy of an Asian-heritage family was deemed of little relevance to the paper’s readers.

The titles went through a succession of disruptive ownership changes, passing from the Illiffe family to the American publisher Ralph Ingersoll, to Midlands Independent Newspapers (a management buyout) and on to Mirror Group, which eventually became the current owner Reach. Slowly and steadily, the internet undermined the business model. Print circulation fell. Job ads went online. The owners kept cutting costs to maintain margins but the decline was relentless.

In attempts to revive interest, the Mail was relaunched in 2001 and again in 2005. The same year, in a symbolic moment, the Post & Mail building was demolished. By 2008, the papers were being created from the converted Fort Dunlop tyre factory in Castle Bromwich, far from the city centre.

Around then, Brummies sought to do better by embracing the internet as a news asset. A buoyant blogging scene emerged from the early 2000s, serving districts such as Digbeth, King’s Heath and Frankley (where B31 Voices continues). A “Social Media Café” blogging group met at Coffee Lounge on Navigation Street. “There was quite a passion for journalism and using new media to shine a light on different parts of the city,” recalls Paul Bradshaw, head of data journalism at Birmingham City University.

This hyperlocal approach followed a Birmingham tradition visible in 1970s publications, such as Handsworth-based Trapeze and the Selly Oak Alternative Paper, points out Dave Harte, associate professor in journalism and media studies at BCU. By 2013, Birmingham had 28 hyperlocal sites, the most of any council area in the country. But the absence of a commercial mindset meant the movement was destined to stall in the late 2010s. “The Birmingham story is that it had energy and potential but it did not organise itself in a way that we could support each other beyond volunteerism and it inevitably petered out,” concludes Harte, a native of Alum Rock who became a blogger in Bournville.

Ignored minorities found a voice in digital media. Indi Deol, from West Bromwich, started DesiBlitz in 2008 to address failures in coverage of Asian communities, especially in relation to “hot taboo subjects”, such as domestic violence, divorce and gang culture. “We wanted to talk about these issues and get them out into a wider environment by using online,” he says. Based in Birmingham’s Great Charles Street, DesiBlitz is a non-profit with a 17-strong team serving cities across the UK. It also makes documentary films and provides training in digital media for students unable to find work in the wider industry. Many West Midlands Asians “do not feel that they are represented properly” by mainstream media, he says.

When Reach launched its regional website in 2018, it downplayed the Birmingham Mail brand and went with something new: Birmingham Live. That was the death knell for the Mail, a signal that — unlike other Reach titles that have kept their names online, such as the Manchester Evening News and the Liverpool Echo — the brand had little residual value with the Birmingham public.

Under the stewardship of Graeme Brown, Birmingham Live is reaching 10 million people a month. While this engagement does not equate to someone buying a newspaper, it is an impressive number. What’s more, the operation is continuing a great Mail tradition, with Jane Haynes, politics and people editor, winning campaign of the year at the UK regional press awards for her work exposing rogue landlords.

Brown, who also edits the Mail, has led campaigns to distribute 11,000 Christmas gifts to Birmingham children in poverty, and to reduce pedestrian deaths and homophobic hate crimes. “Because we truly respect and understand our audience, we're also able to make a big impact with our public interest journalism,” he says, praising the “talented journalists” in his 40-strong team, who are thankfully back in the city centre, at Brindleyplace.

Yet the many district offices have closed and the print newspaper’s days are surely numbered. Today, Birmingham Live has competition from veteran regional publisher David Montgomery and the Birmingham World website. The city needs this free-to-access information at scale because it cannot simply rely on the BBC to provide it.

There is no longer a need for the queues of newspaper vans that once formed along Printing House Street because the golden era of The Great Evening Paper has long passed. But the appetite for news that once sustained it lives on, as seen in the growth of The Dispatch, DesiBlitz, B31 Voices and no doubt more outlets yet to come. Such diverse voices are building the new future for West Midlands media that the people of the region demand and deserve.

Comments