By Jack Walton

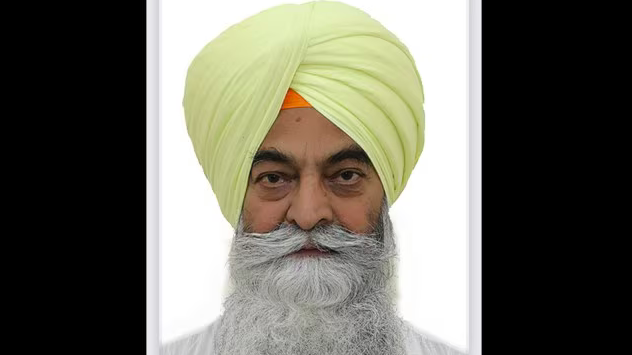

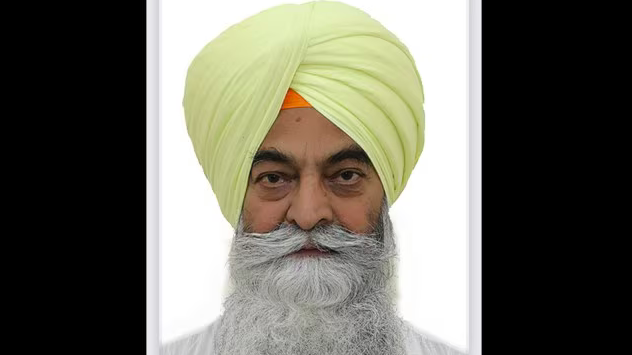

When Ranjit Sahota found out that a convicted terrorist was set to become a trustee at his local gurdwara, he was less than thrilled. To Sahota, and indeed many other members of the Guru Nanak Gurdwara in Wednesfield, the facts are the facts: in 2006, Punjab Singh (alias Dhadi, alias Paramjit Singh) was arrested on suspicion of terror offences in his native Punjab. Parkash Singh Badal, then Chief Minister of Punjab, claimed Singh was “entrusted the job to kill me”. Sahota wasn’t alone in his misgivings: 276 members of the Guru Nanak Gurdwara congregation signed a petition expressing opposition to Singh’s trusteeship.

But despite his opponents, Singh remains in the role. He says he’s an innocent man, wrongly persecuted by the Indian government for singing folk songs criticising their regime.

When I reach out to Singh to discuss the allegations against him — as well as wider concerns some members have about how the gurdwara is run — at first he’s unresponsive. I have more luck with his ally, Balbinder Bajwa. Bajwa politely informs me I’ve been presented with “misinformation” which he will have no issue “correcting”. When I mention the promised “corrections” to one member of the congregation, who spoke to The Dispatch on the condition of anonymity, their reply is blunt: “You cannot trust Balbinder Bajwa”.

Singh was appointed trustee three years ago, and remains one today, but the issue hasn’t gone away. His appointment, as well as a litany of other accusations directed at the trustees, have left the temple in disarray, with claims of threatening anonymous letters, byzantine governance disputes centering on the validity of a document drawn up four decades ago and some kind of mini civil war between two factions.

On one side is a group who say that Bajwa, Punjab Singh and the trustees are attempting to steal the gurdwara away from the community it serves. On the other are Bajwa and Singh, who say their opponents are a small minority and send me a six-page letter detailing their version of events. The letter refers to their opponents (some of whom are members of the temple’s former management committee) as “assailants” and describes “a systemic campaign of harassment and abuse, including threats to “kill”. Furthermore, the two men assert, The Dispatch ought to tread carefully — Singh is a “well-known national and international singer” and any attempt to damage his reputation will be met “with the full force and arm of the law”.

The following day, I receive a lengthy text from Singh’s daughter, a solicitor, saying she intends to contact West Midlands Police “this morning” as I am “empowering those who the police are trying to protect my dad and others from”. When I ask in the afternoon if that police report has gone in, she doesn’t reply. I’ve yet to hear from West Midlands Police.

To understand the present, you have to return to the past. Indian court documents from 2011 state that at the time of his arrest, Singh was “roaming” in Jalandhar, an ancient city in the north Indian state of Punjab, when police received a secret tip-off. They’d heard that Singh, as well as two other men, were carrying a large cache of RDX — an odourless, tasteless compound often used as an explosive — as well as other explosive material. When the three men were arrested, the police said they recovered six kilograms of RDX, six detonators, seven timers, one battery, electric wire, and one walkie-talkie set, along with two hand grenades, one pistol with 50 live cartridges and a square magazine.

After being detained in an Indian jail, Singh’s family sprung into action. The Sikh Federation — an organisation in the UK that promotes Sikh issues — contacted 200 MPs in the hope of assistance. Ken Purchase, then MP for Wolverhampton, said he hoped that Chancellor Gordon Brown would raise the matter with the Indian government on an upcoming visit. Singh’s daughter said at the time that the Indian police had changed their story in what was an obvious “fit-up”. She led the campaign for his freedom.

When Singh presented in court following his arrest, his family said he was weary from days of torture. “His legs were painful and he could barely walk. He said they kept standing on his back and legs to try and force him into signing a confession,” his wife, Balvinder Kaur, told the press at the time. But Singh’s proclamations of innocence were no use. In November 2008, the three men stood trial and were sentenced to five years imprisonment. As far as the records go, they are convicted terrorists.

Singh is now back where he has been most of his life, and where he once worked as a foundry worker: Wednesfield in Wolverhampton. But many at the Guru Nanak Gurdwara seem to be uneasy about his convictions. When he was first appointed trustee, there was opposition. Singh had been brought in by Balbinder Bajwa, himself a controversial figure. Despite being one of several trustees, Bajwa is considered the de facto leader of the gurdwara by those who spoke to The Dispatch. While the position is not a paid role, trustees do have the power to appoint people to the temple’s management committee, which is in charge of day-to-day operations and finances. A view began to form among members of the management committee that Bajwa and Singh did not have the temple’s best interests at heart.

A builder by trade, as a trustee Bajwa allegedly gave himself several contracts to do work at the temple, the finances of which his opponents claim were not properly declared. Many felt uneasy about a trustee of a gurdwara making money from it at all.

“I made it clear we should have no financial gain as its a place of worship,” one former management committee member says. “[Bajwa] thought: ‘Great, I can do building work and charge for it.’” Another calls Bajwa’s actions an “outrage”. To be clear, Bajwa was not known to be doing anything illegal, but many found it immoral. They also had no idea if there had been a proper tendering process for the work.

There were separate issues, too. During lockdown, eight teachers at the Punjabi school that the gurdwara operated were sacked, which according to Bajwa was because they “were not taking their positions seriously”. Meanwhile, a new headteacher, Amrik Singh, was brought in. The new hire was not only a relative of Punjab Singh, but he didn’t appear to have any teaching qualifications (Bajwa and Singh insist he is “a person of integrity” who was requested by the parents of the children at the school and who has since increased the numbers of children attending). The Dispatch has seen a letter signed by the eight sacked teachers expressing concern. “This new principal has no teaching Qualification or teaching experience,” the letter reads. “Therefore, he is not the right person for this post”.

Members of the gurdwara’s management committee began to challenge Bajwa and the trustees over their decisions. One former member tells me his questions consistently fell on deaf ears. Were the children at the school properly safeguarded? Did any of the teachers undergo DBS checks? And crucially: was the new trustee Punjab Singh a terrorist?

Opinions on Singh’s conviction vary. Some see the Indian government as a bad-faith actor and believe his story of a miscarriage of justice is very plausible. However, it appears there is a large block at the gurdwara (the 276 members of the congregation who signed the petition) who are strongly against his involvement, although even this is disputed by Bajwa, who claims the signatories were duped and didn’t know what they were signing. He also claims many of the signatories were not even from Wednesfield — though when I ask him to evidence this claim he fails to do so.

Amid the disquiet, in April 2022, some members of the congregation came forward to demand the resignation of Bajwa. Bajwa himself says this was a “WhatsApp viral campaign” rallying a number of young men to congregate at the gurdwara and threaten his fellow trustees. Furthermore, he accuses Sahota of urging his faction to “behead” the trustees (a remark Bajwa seemingly interprets as a murderous threat, but which Sahota says was obviously figurative — adding that if there was a serious threat of an actual beheading then surely police would have been involved ).

One former management committee member, who has asked not to be named, says the running of the gurdwara “descended into chaos”. The serious question this raised is who exactly the gurdwara is answerable to. For years, it referred to a Declaration of Trust document signed around 1980 (the exact date isn’t clear) that set out the basic constitution and governance. On the other hand, it was operating as a charity, receiving significant donations with an income of over £300,000 per year and a school responsible for the education of many children. One member of the congregation calls the Declaration of Trust a “ludicrously out-of-date document”. Yet some of the trustees insisted it was not a charity and that registering it as such would be anathema to Sikh principles.

According to the anonymous former management committee member, the document is was “drawn up in about 1979 by a group of men who were not very well educated.” He goes on: “[Balbinder] Bajwa points to this document, but if you ask the present five trustees what is your role, they haven’t got a clue… they’re welcoming in a man who was sat in an Indian jail for five years on terrorism charges”.

The dispute between the two factions has resulted in a febrile atmosphere. One woman said she came out of a meeting at the gurdwara only to find her car had been keyed, while a man allegedly received a threatening anonymous letter. (Though the woman admits she can’t know who vandalised the car, and that there is no evidence to suggest who was responsible for these actions).

By February 2023 the conflict had shown no sign of dying down, so members of the congregation reached out to the Sikh Supreme Council (SSC) to mediate. Both sides of the dispute signed a document promising, “Whatever decision the Sikh Supreme Council decides we will abide by this.” The SSC ruled that the finances of all refurbishment work during lockdown (much of which was work done by Bajwa) should be published and the dismissed Punjabi school teachers should be reinstated, among other measures.

It seemed as though after months of chaos, some kind of resolution had been found. But instead of implementing the recommendations, Bajwa disbanded the gurdwara’s management committee, appointing five nominees of his own to run things and even changing the locks to the main office where cash and the petitions against Punjab Singh were being held. When I ask Bajwa why he failed to comply with the SSC’s requests, he claims the SSC’s mediation was never completed, again due to “threats” by “assailants”.

Bajwa insists he had no choice but to save the Gurdwara from a management committee of (again) “assailants” who stole the minute book (a crime he says he has reported to West Midlands Police), oversaw a fall in income and failed to account for missing money — although when The Dispatch asked to see evidence of these financial problems, he did not provide it. He says the removal of the committee was “constitutional” and that his trustees have been “transparent at all times of the spending, and this is very well documented in the Gurdwara accounts”. (One congregation member says this is “laughable”).

Ranjit Sahota has attempted to flag Punjab Singh’s involvement at his gurdwara to the Charity Commission but says it’s been a frustrating process. In a February 2024 email seen by The Dispatch, the Charity Commission says that because Singh’s convictions occurred under Indian legislation, “automatic disqualification provisions in the Charities Act 2011 do not apply”. In their lengthy letter to The Dispatch, Bajwa and Singh point to this decision, adding that the campaign for Singh’s release was widely supported back in 2007 and that the convictions were eventually “overturned”. When I ask to see evidence of the convictions being overturned, it isn’t forthcoming.

The Indian government, meanwhile, still appears to be keeping tabs on Punjab Singh. In December last year, he was arrested on another visit to India at Amritsar's Sri Guru Ram Das Jee International Airport and named in the Indian press as “a close aide of Pakistan-based Khalistani terrorist Lakhbir Singh Rode”. Bizarrely, he was released a few days later, with the police claiming it was a case of mistaken identity.

At the Wednesfield gurdwara, a similar lack of clarity persists. Ranjit Sahota is astonished at the inaction of the Charity Commission and has recently filed a new legal case against the trustees. The bottom line, he insists, is that Punjab Singh has been convicted of terror offences and should be nowhere near a trusteeship. Others believe the questions surrounding Singh’s convictions are secondary. “To be honest, I don’t want to comment on what he’s done in his past,” the former member of the management committee says. “What I care about is whether him and [Balbinder Bajwa] are able to run a gurdwara. And they are not.”

Comments