“I felt like I spent my whole teenage life waiting for buses that were always late,” Daniel Knowles tells me. Knowles — no relation of The Dispatch’s editor Kate — grew up in Moseley, and went to school at King Edward’s Five Ways in Bartley Green. His experience would resonate with many who have had to commute without the car: catching buses that could take anywhere between 45 and 90 minutes. The famously bad traffic that blights much of the city turned a relatively short-distance journey into an agonising ordeal.

As is customary wherever cars are essential for getting around, Knowles started learning to drive the moment he turned 17. But there was a snag. “I sucked as a driver” he tells me — not checking his mirrors; pulling out at the wrong times. At the end of the lessons his parents had bought for him, the instructor was blunt about his prospects of passing a test. “Absolutely no chance.”

Though Knowles can now drive, his experiences have given him an insight into what living in a car-dominated world feels like when you can’t. Over time, his job as a high-flying reporter for the Economist magazine has taken him to live in other congested cities — Nairobi, Chicago — and he’s begun to spot a pattern. The cities that have made it as easy as possible to travel by car are in fact the hardest to drive around, due to the sheer weight of traffic.

He’s channelled the trauma in a constructive direction, writing a book about it: Carmageddon: How Cars Make Life Worse and What to Do about It. As the title suggests, it’s not exactly positive about the impact of cars on our lives.

I wanted to speak to Knowles, because it seems to me his forthright views on the downsides of driving — which might have seemed an extreme environmentalist position just ten years ago — are starting to seep their way into the mainstream.

We can see this in Birmingham. This year, the tragic deaths of people like Azaan Khan, a twelve-year-old boy killed while cycling in South Yardley, have prompted a growing backlash across the city. It’s been notable that, where people would previously blame the individual driver for their dangerous driving (and in many recent cases, the influence of drugs and driving over the speed limit have been factors), the ire of protestors from groups like Better Streets for Birmingham has been broader. They think the car has been given too much free rein, full stop.

Councillor David Barker, who represents Brandwood and Kings Heath ward where fatal collisions have taken place, didn’t mince his words earlier this year, saying: “I, for one, will try my damndest to stamp out this toxic car culture that’s not only breaking the law but also putting people’s lives in real danger.”

But that’s pitting Birmingham City Council against the current trend of government thinking. The council recently committed to “review all existing 40mph speed limits across the city, with the intention that almost all will be revoked, with these becoming 30mph” — the kind of statement Rishi Sunak might be referring to when he describes a “war on motorists”. National policy is speeding up; Birmingham is trying to slow down.

The birth of a car culture

Though I didn’t grow up in Birmingham, the association has been there for me from a young age: I was a keen fan of the TV programme Brum, where the city is the backdrop for a classic car’s adventures. Knowles remembers his dad taking him to the motor show most years (“At the age of 12, I had very strong opinions on all the different brands of cars”, he tells me).

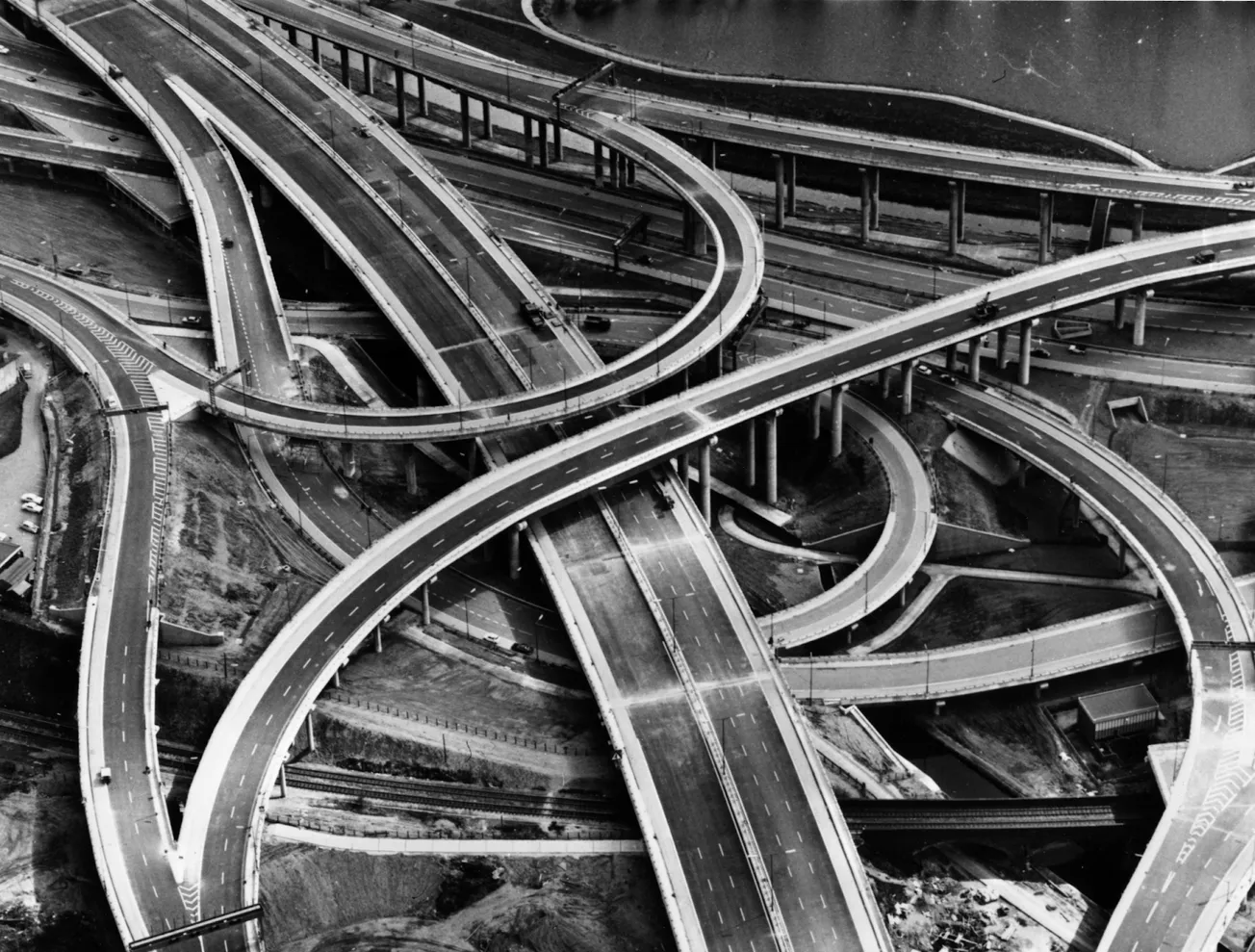

In his recent book Second City: Birmingham and the Forging of Modern Britain, the historian Richard Vinen writes about “the general restructuring of Birmingham around the car,” in the postwar period. Herbert Manzoni, the man who reshaped Birmingham as its City Engineer and Surveyor between 1935 and 1963, envisioned it “as the epitome of American-style modernity,” Vinen writes. Interestingly, he notes that a lot of Birmingham’s new roads were originally supposed to be hidden from view. “The post-war townscape might have been different if Manzoni had achieved his initial ambition to put cars into tunnels and leave pedestrians on the surface.”

The book recounts how a newcomer to Birmingham in the 1960s “found that women in the grandest houses could tell him nothing about bus routes.” “We are all two-car families in this part of Moseley now,” she reportedly said.

By 1971, the city had become “dominated by the motor car,” according to a journalist at the time. “Strangled by a concrete collar of ringways, flyovers and interchanges, it is as if it has been enslaved by its own creation.”

Nowhere epitomised the city’s association with the auto industry more than the Longbridge plant. The first Austin car was built here in 1905. It expanded following a merger with Morris, and in 1952 produced its most famous car: the Morris Mini Minor (which became known as the Mini). It remained a major employer, even as the company (which became MG Rover) increasingly got into financial trouble. MG Rover was so significant to the Birmingham economy that when the factory closed down in 2005, the city entered a mini-recession.

As well as making cars, Brummies became ever more likely to own them. We can track this rise using data from the Census. Conducted every ten years, these ask people how many cars they own. In 1981, around half of Birmingham households had no cars at all – for the first few decades of the city’s road-building programme, it was mostly middle-class people who owned them (“The city was built around the convenience of drivers long before the majority of its inhabitants had a car,” notes Vinen). By 2021 the proportion of no-car households was less than a third. The number of households owning two or more cars has roughly trebled.

So how does that impact our roads? Because road space is given away for free, it becomes subject to what economists call “the tragedy of the commons”. The first (hypothetical) person to get a car has incredible freedom — they can get wherever they want quickly on the wide open roads. So can the second. But as more people join the road network, they start imposing limits on each other’s freedom. The resource (the road) is overused, and everyone suffers. That’s exacerbated by building housing developments and suburbs where it is assumed everyone will own a car, so public transport links go unbuilt.

Knowles tells me there comes a moment when, as car ownership grows, the experience of driving flips from freedom to frustration. Cities like Birmingham are well past it, and increasingly cities in the developing world, where car ownership is on the rise, are clogging up too.

And the data seems to suggest Birmingham really is the worst part of the UK for this. Research by the Resolution Foundation think tank has found that the West Midlands Combined Authority has the worst road delays (by some margin) among English city regions. An average vehicle driving an average mile on the area’s strategic road network (motorways and major “A” roads) will be delayed by twenty seconds. That adds up pretty quickly (and will be much higher at peak times). And it’s significantly worse than in the areas surrounding London, Manchester, Leeds, and Bristol.

The report notes that “this degree of car congestion suggests that economic activity is already constrained”, and that this is stopping the city centre from attracting more workers, who would otherwise be able to access well-paying jobs there. The costs in time, petrol, and stress arising from traffic make it just not worth it for many people. As Knowles puts it to me: “the number of cars, and their use, is a real drain economically on the city”.

It’s worth pausing to appreciate how significant this is. Cars — the 20th-century symbol of prosperity and economic growth — are now actually delivering the opposite for Birmingham; holding back, rather than enabling, its growth. Inrix, a provider of traffic data, estimates that congestion costs Birmingham’s drivers £346m in 2022. That figure is more than 1% of the city’s total economic output, and almost certainly underestimates the true cost to the economy, in terms of lost worker time while driving, delays in moving goods, and health impacts from long periods of commuting.

One response to that is to build more roads, or widen the ones we already have to accommodate more cars. That’s been done many times before, but it hasn’t solved the traffic problem — in fact, the opposite. By making travel by car more efficient for one section, it brings more cars onto the network, worsening other bottlenecks. In any case, in much of built-up Birmingham, there’s no realistic prospect of providing more space for roads.

Cars vs CAZ?

So what about another approach: reduce road use by charging drivers? We now have the Clean Air Zone (CAZ) which charges older, more polluting vehicles that go within the inner ring road. It’s been in place for two years, and does seem to be doing the job of improving air pollution: a recent council report found that Nitrogen Oxide levels had fallen by 17% since 2019, and that over two years the proportion of vehicles which are non-compliant has dropped from 15% to just 6%, as people upgrade their vehicles.

Knowles tells me his father now refuses to pick him up from New Street station when he goes home, as the family’s old diesel Mazda doesn’t make the standard. His father has also bought an e-bike to “defeat the money-grubbing bureaucrats” – which, of course, is exactly the kind of behaviour change the CAZ was designed to bring about.

But while the CAZ does seem to be achieving its objective of improving air quality — by prompting drivers to upgrade their vehicles — it doesn’t seem to be doing anything to reduce congestion. In fact, the number of vehicles entering the zone each day has increased (from 98,112 in its first year to 102,392 in its second). While London has both a congestion charge and an air pollution charge (ULEZ), Birmingham’s set-up isn’t designed to stop people driving, just to get them driving cleaner.

The other main difference in London, of course, is the quality of the public transport to get us about. The public would be unlikely to put up with a congestion charge, because in many cases there is simply no alternative to driving. The city’s buses score poorly for unreliability — research by data analyst Tom Forth has shown that in peak times Birmingham becomes a “small city” where only those who live near the centre (or on a train line) can get there. Forth’s work suggests that most of Birmingham’s productivity gap (compared to what you would expect from a European city of its size) might be explained by how few workers can get to central Birmingham at peak times.

Areas where people can get to Birmingham CityCentre by 30 minutes’ bus journey

Some progress is being made. The West Midlands metro is small compared to the tram network in almost any comparably sized European city; but it is growing, with extensions to Dudley and Digbeth currently under construction.

On the bus front, though, metro mayor Andy Street has remained equivocal about whether to push ahead with bus franchising — something being taken forward in Greater Manchester and Merseyside. The advantages of franchising — being able to control the timetable and link up routes — have led to much better bus performance in London, which unlike most of the rest of the country didn’t have its buses deregulated. While trams are fast and shiny, most people will continue to need to use the bus if they’re not driving.

How people living in Birmingham travel to work

Dethroning the king

The car is still seen by many as vital to Birmingham’s economic success. The region has been for some years trying to get to the front of the electric vehicle battery manufacturing queue, by creating a “gigafactory”. Street – whose name befits a road-heavy conurbation – has described himself as “utterly obsessed with securing a Gigafactory for the West Midlands due to the huge economic and job benefits it would bring”. The old Coventry airport site has been earmarked for it.

But the plan is stalling — despite extensive efforts to woo Tata, the owner of Jaguar Land Rover, they have opted for a site in Somerset. The council says they are pursuing other options, including talks with Asian businesses, but nothing has been officially confirmed yet. As for Longbridge, the former heart of Britain’s auto industry has been transformed into a retail destination, against all evidence termed a “town centre”, with a massive car park at its heart.

But with so many decades of “designing in” the car, designing out the traffic that cars have created won’t be a quick fix. Despite that, Knowles remains hopeful. “A world in which cars are less necessary in our daily lives, and less dominant in our cities, is possible. We just have to find a way to get there.”

Join our free mailing list to get high quality journalism about Birmingham and the West Midlands in your inbox from The Dispatch.

Comments