By Kate Knowles

1986. The fag end of a night out dancing. Surrounded by sweaty men in a nightclub with black-painted walls, the euphoria in the air gives way to a bittersweet feeling as the sound of a drum machine kicks in. Against a slow rhythm, the soaring, yearning torch vocals of a European disco singer fill the room. One final sway among the dry ice, lasers and cigarette smoke.

The slow dance was an end-of-the-night tradition at The Nightingale nightclub in Birmingham, and Rose Laurens’ ‘American Love’ was often the song of choice. “Play this to any gay guy over 50 who went clubbing back in the ’80s and watch his face,” says Dolly, a former DJ at the club. For many gay men in Birmingham at the time, The Nightingale was a home away from home; a place to connect with a community that had been steadily growing since 1967, when homosexuality (in private) was first decriminalised.

Several groundbreaking moments in Britain’s gay history had taken place in Birmingham in the intervening years. As in Manchester and Bristol, a gay quarter began to materialise and the country’s first gay community centre opened. Within this vista stood the Sentinels: the two, sparkling white tower blocks of social housing that became home to many gay men. Then the AIDS epidemic broke, tearing through the fabric of their lives.

For this piece, we’ve spoken with gay men who lived through the AIDS crisis and we’ve drawn from the extensive Gay Birmingham Remembered archive. The article is also informed by two texts: A 2009 thesis by Jeremy Jospeph Knowles on gay activism in Birmingham and a forthcoming book, Radical Acts, by HIV historian George Severs.

This is the story of how AIDS threatened the burgeoning Birmingham gay scene and how its members fought back against a hostile society. It is also about the importance of having a place to party, in both good times and bad.

‘We created our own little world’

British gay activism flourished in the 1970s, a decade that beckoned in a newfound radicalism. The Gay Liberation Front (GLF), modelled on the US movement that emerged after the Stonewall riots, was unapologetic: coming out and living openly as a gay man was seen as a crucial step in the fight for equality. After London, Birmingham’s GLF, founded in 1972, was one of the most active groups of its kind in the country. It produced one of the first sex education pamphlets for gay boys, Growing Up Homosexual, and organised discos in pubs like the Eagle and Tun and the Shakespeare as alternatives to the commercial gay bars. The GLF’s strength culminated in the establishment of the Birmingham Gay Community Centre in 1976 — the first of its kind in Britain.

What is now Birmingham’s Gay Village was just a few bars and a nightclub in the early ’80s, but this cluster of watering holes was thrilling to men of all ages, who ventured on their first nights out on the emerging scene. Partners (formerly the Windmill) and The Jester were both cellar venues, accessed by a flight of stairs. Everyone gathered inside would look up as a new person entered — a nervewracking prospect for the inexperienced, akin to a kind of debutante presentation. You were ‘coming out’ to the community, quite literally.

“It was one of the first places where a lot of us younger people went to, very nervous,” says Garry Jones, who paced the pavement outside The Jester several times before plucking up the courage to head in. “Especially if you were new, you know, a bit of fresh meat.” Phil Oldershaw, formerly a “fully fledged heterosexual”, was taken to Partners by his first boyfriend. As he descended the stairs, a little tense about being revealed to the crowd below, the room rose into view and his nerves ebbed away. “You suddenly see all these people that are the same as you,” he says, “and they’ve had the same experiences and actually sleeping with a man wasn't such a bad thing and all the lights and the smells and the colours and the music. It was very uplifting.”

Marc Cherrington, aka Cherub, had a tough upbringing in Dudley and was still a child in the late ’70s. He first set eyes on The Jester from the bus window while on a shopping trip with his mom. He travelled back into Birmingham on his own and sat on the grass verge in front of The Sentinels, across the road from the bar, and watched as men went in. He looked down at The Jester and said to himself, “one day, I’ll go in there.” Then he looked up at the Sentinels and said, “one day, I’m gonna live in there”.

When the day came, he was just 11 years old. He was tall for his age, and told the doorman, Johnny Prophet, he was 16. He entered. “All the heads turned,” he says, “because I was a blonde hunky boy. And I never, ever bought a drink.” For Cherub, who had been neglected and was a survivor of sexual abuse, the gay scene held the promise of a family. “For my generation, a lot of us ran away from home, so the community looked after us. It embraced us and took us in,” he says. “We created our own little world.”

A dispatch from America

Unfortunately, by the tail end of the 70s, the Birmingham GLF had all but petered out. Despite the advances made, most gay men were still more comfortable meeting in private. Bars were often underground, literally, or the windows blacked out.

“In the ’80s the gay scene was very small,” says Bill Gavan, who is today Mayor of Sandwell. Back then he owned The Lord Raglan pub in Wolverhampton, and later the superclub Gavan’s and Birmingham’s Subway City. “We were backstreet; anonymity was very important.” The Lord Raglan was an old 1960s-style pub with a back room and a lounge bar. In the daytime it was a “normal” pub, where Bill and his partner David would serve food. But in the evening, a closed sign went across the door and “gay people came from far and wide”.

Also in Wolves was the legendary Silver Web, run by an eccentric sister and brother called Bettie and Norman. Norman would frequently wear white trousers through which his heart-patterned briefs were visible, and Betty donned a memorable wig. The police raided the place several times, at which point underage regular Cherub, abandoning his martini, would hasten through a back door and down a fire escape to hide in an outside bin. He was never caught.

Although hidden away, the nights were electric. The Lord Raglan hosted drag queens up from London and produced two pantos every year: one for the outside world with a chaste title (Sleeping Beauty), another for the raucous gays and lesbians (A Prick in the Hand). “It was outrageously wonderful,” says Gavan. “It was a room full of poofs and dykes having a wonderful night out.”

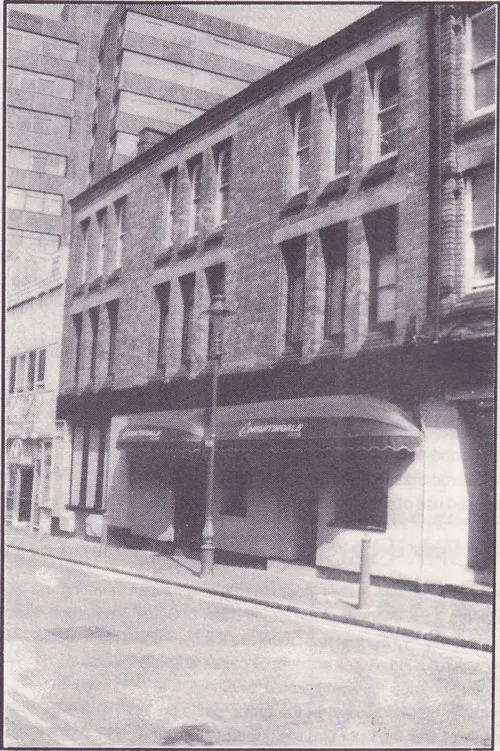

However, of all the West Midlands spots, it’s The Nightingale that stands out. Founded in 1967, it was a first for the city at the time: a venue run by gay people, for gay people. In the early 1980s, the nightclub was on Thorp Street, where the Hippodrome’s Patrick Studio is today. To get in, you’d have to knock the door and a host on the other side would look out at you through an eyepiece, then open up and ask you a series of questions. “Whether you read the Gay Times, things like that,” says artist Garry Jones who regularly travelled to the club from his home in Coventry. Once inside, it was a cornucopia of male gay life: skinheads, leather men, clones, twinks, older guys, transgender people. “It seemed like everybody was friendly towards each other and looked after each other,” says Jones. “You sort of felt that you were coming home.”

But this idyllic period wouldn’t last forever. One weekend in the summer of 1982, not long after he moved to the West Midlands from Kettering, Jones was reading the Sunday papers. In amongst the news about Charles and Diana’s new son and IRA bombers in London, he noticed a small article — a dispatch from America. It was a report about gay men in San Francisco who were getting sick.

‘We’d start noticing people disappear’

A man from Birmingham was among the earliest people in the UK to become HIV-positive. Jonathan Blake, who lived in London by July 1982, was suffering from swollen lymph nodes when he checked into an STI clinic. He was told a few months later that there was nothing the doctors could do (in the film Pride, which dramatised the 1980s coalition between London gay and lesbian activists and Welsh miners, Dominic West plays a character based on Blake). Blake is alive and well to this day.

The virus, which had first been seen as an American thing, was now seen as a London thing by many gay men in Birmingham. But over the next two years, it found its way to the West Midlands. The first cases of AIDS emerged here in late 1984. “It sort of slowly happened,” says Jones. “We’d start noticing people disappear.” He’d be out and about and remark to friends that someone they knew hadn’t been around for a while. Then he’d hear that they’d “gone home” or in the worst cases, passed away. “But then it got so that people were dropping like flies and it was really, really scary,” he says. Gaunt faces would appear on the dancefloor at The Nightingale, or in The Jester and the other men would know, without having to be told, that they had succumbed to the virus.

Over in Wolverhampton, Bill Gavan would see once strapping regulars at The Lord Raglan become emaciated. “I think the most devastating thing about when HIV hit in those days,” remembers Gavan, “was people would be tested for HIV, diagnosed, then it'd be full blown AIDS within about six weeks. And they’d be dead within three months.”

In the absence of substantial public health guidance, misinformation began to swirl. The stigma attached to AIDS patients was brutal, and came from lesbian and gay people as well as the heterosexual world. “You could even see amongst our own communities that people were frightened to go near them,” says Gavan. People would smash glasses that had been used by the ill customers, mistakenly thinking HIV could be contracted via saliva. At The Nightingale, healthy customers would refuse to drink from glasses even when they had been washed. In a scene that was predominantly made up of white men, “vicious rumours” developed that you’d get the virus “if you slept with a black guy”, says Cherub.

The response by the medical establishment and the press was hostile. The Birmingham Evening Mail quoted a doctor saying “homosexuals are homosexuals and that’s all there is to it,” concluding that nothing could be done to treat them. “You can’t make them better, you only frighten them to death,” he continued, insisting there was no point in tracing their sexual partners. “You may just as well leave them to present themselves if they actually end up having AIDS. I can assure you the homosexual population knows more about AIDS than you or I.” Meanwhile, national tabloids put out scaremongering headlines about a “gay plague” and “gay cancer”.

The Pearly Gates

In a hostile world, these men needed a refuge and, for many sufferers, that was Clydesdale and Cleveland Towers, known collectively as The Sentinels. Built in 1971, the towers sit opposite the present day Birmingham LGBT Centre and next to the Holloway Circus (Pagoda) Roundabout. They were erected as part of a major project to modernise the city centre, and a scheme to provide council homes in the post war years. The flats were less popular with families, who often wanted to live in the suburbs, but a huge hit with gay men, thanks to their proximity to the gay quarter. The buildings quickly became known as Dorothy Towers, a reference to the “he’s a friend of Dorothy” euphemism that was used to suggest a man was homosexual.

“Why wouldn’t you want to live on the doorstep of the bars and the shops and the clubs?” asks future resident David Coffin in Sean Burns’ documentary, Dorothy Towers, about the blocks. By the time he moved in, they had:

“A reputation for being a safe space for gay men to live in, a reputation for being somewhere you could go and get laid, somewhere you could go and chill out after a heavy night if you couldn’t get home, a reputation where someone would look after you.”

This impression of the towers as somewhere gay men cared for one another was likely cemented during the long, heartbreaking years of the AIDs crisis. Future resident Twiggy, the legendary drag artist, has said they were seen as a “bit of a dumping ground for those diagnosed with HIV”. The buildings became known by a new, more morbid nickname: “The Pearly Gates”. In the early 1990s a newspaper article also appeared, explains resident William Gibson in Burns’s film. The story implied HIV positive, gay men were being given preferential access to council flats in the towers and had turned them into a “gay ghetto”. This added fuel to the fire of stigma, and an extreme far right group graffitied “Combat 18 AIDS fuckers get out” on the side of Cleveland Tower.

Cherub, who fulfilled his childhood dream of living in The Sentinels, has been there for 30 years. He has fond memories of those who lived there and died, many of whom also worked at The Nightingale. Dada Pops, Lulu, Alan, Mother Goose, Nana Rubes, a coterie of bright characters gone. “They deserve to be remembered,” he says.

‘No funeral, no nothing’

Thatcher’s government was famously slow to respond to the crisis, leaving communities across the country to develop their own support networks. The Nightingale hosted a conference on AIDS on 9 December 1984 that was attended by about 70 people, including several doctors and Tony Whitehead of the Terrence Higgins Trust. As a result, the volunteer-led AIDS counselling group AIDSline West Midlands was formed.

Other informal initiatives and forms of support grew. As a local pub landlord, Bill Gavan became a go-to person for sufferers who needed help. The Lord Raglan set up a support group and a slush fund for basic necessities: soap, food, and a case of their favourite drink. These men were “young, handsome, healthy, professional people” and within months were wasting away, “housebound, more or less neglected, living on dole money,” says Gavan. “[They were] dying, no cure. Hopeless, absolutely hopeless”. Later, in Birmingham, where he owned Subway City nightclub, he purchased a large Edwardian house in Soho. He converted it into six furnished and serviced flats; anyone with HIV or AIDS could live there for free.

“People really looked after each other,” says Garry Jones. In the face of extreme institutional ignorance, they had no other choice. In Coventry in 1985, Jones and ten others had to rally around to help the partner of a friend of a friend. His partner had died in the hospital within two or three weeks of getting AIDS, but terrified staff refused to touch his body, and neither would an undertaker. It fell upon one of the friends to locate a bodybag, another to get hold of a van and the group to tenderly move his body themselves. They had to bribe a crematorium, and the friends were responsible for removing his ashes. “We just scattered his ashes. He had no funeral, no nothing,” says Jones.

‘The best of times and the worst of times’

As Jeremy Knowles writes in his thesis about AIDS and Birmingham’s gay community, in the late-1980s, the UK’s gay population and their supporters mobilised at an “unprecedented” level. More than 300 activists from around the UK convened in the village of Wombourne near Wolverhampton in early 1986. They had gathered to support a group of protestors being tried at the local magistrates court. The Wombourne 12 had been arrested on trumped up charges of abusive and threatening behaviour, and in one case, assaulting two police officers (despite the accused lesbian having been assaulted by police herself).

The demonstration had occurred outside the home of the Conservative leader of South Staffordshire Council William Brownhill, who the previous December had called for the extermination of 90% of lesbians and gay men. “I should shoot them all,” Brownhill was quoted as saying in the Express and Star. “As a cure I would put 90 percent of queers in the ruddy gas chamber.” South Staffs Labour leader, Jack Greenway, publicly supported his comments.

By 1987, the government had finally been forced into action. The infamous “Don’t die of ignorance” campaign launched. If any of the men weren’t afraid before, they were now, as huge tombstones with AIDS carved into them shot through their letterboxes on leaflets and loomed from TV adverts. “It’s spreading,” boomed the actor John Hurt in the voiceover. One upside to the campaign was that it clarified anybody could become HIV-positive — the authorities were finally making it clear that the disease didn’t only affect gay men. Still, it was unfortunate timing for Dolly, who was 20 and had come out to his family just a month earlier. “I thought: ‘Well, there’s my welcome to the gay scene!’” he laughs.

A shy young man who lived with his mom and three brothers, Dolly tentatively started going out alone. Birmingham’s gay nightlife hadn’t stopped during the crisis, but as Dolly would discover, there was a discernible sense of caution in the air. He tried The Nightingale a few times, but was always surprised by how empty it was. One evening, at about 10:45pm, he made his way to leave when the host, bewildered, asked him where he was going. “They’ll all be here in a minute, no one comes until the pubs shut,” he said. Dolly stuck around for long enough to see a “tsunami of homosexuality” pour in through the doors. Wanting to be safe, Dolly asked the barman if there would be any sexual activity inside the club and was told: “Nah, they’re all being careful at the moment. They’re terrified.”

Eventually, Dolly would start working at The Nightingale, where he became friends with Cherub. He became a DJ, preferring the relative calm of the booth where he wouldn’t be bothered by too many people. Despite the often sad and scary circumstances of the epidemic, he looks back on those years with affection. The Gay Village was a places to let go, laugh and dance your heart out. “That’s what The Nightingale was, it was: leave your troubles at the door,” says Phil Oldershaw who went on to manage the club and co-founded gay pride in 1997. “There will always be a need for gay spaces,” says Andy King who owns The Fox Bar.

From Dolly’s position in The Nightingale’s DJ box, he could see everyone in the room and knew their faces, if not their names. He would notice when a regular came in looking thinner, more tired around the eyes. He would notice when they didn’t return.

“The music carried us through the bad times. I hear some songs now from the late ’80s, and it chills me to the bone, as it takes me back to that point of memory in the club,” he says. “It really was the best of times and the worst of times.”

An earlier version of this article suggested Phil Oldershaw owned The Nightingale at one point. He was the manager, and the copy has been corrected to reflect this.

Comments