Dear readers — today's story is about a cult West Midlands film that has influenced everyone from famous directors like Robert Eggers and Danny Boyle to local musicians and artists. The film explores the mystical resonances of the West Midlands countryside and the legacy of the ancient Saxon kingdom of Mercia. Intrigued? So are we...

But first, The Dispatch Christmas quiz!

Christmas is nigh and we’re feeling festive at The Dispatch. It’s been a fantastic, hectic year, so what better way to celebrate than bringing our community together in a beloved local bar and getting them to duke it out for a £100 cash prize?

That’s right; on 18 December, The Dispatch is going to be hosting its very own Christmas quiz! We’ll be taking over the Jewellery Quarter’s Temper and Brown, for an evening of testing your knowledge on everything from music, history, pop culture and — of course — Birmingham.

Tickets are £3 for The Dispatch's paying supporters (use your code) and £4 for free subscribers and non-members (who are extremely welcome to come along). Minimum teams of two and maximum six; the winners will receive £100 in cash. There will also be plenty of time for mingling after the main business of the evening has wrapped up.

Join us from 7.30pm on 18 December for some classic Christmas celebrations

“I wonder about a man, a thousand years before Joan of Arc, a man, a king of Midland England, last of his kind, the last pagan king of England,” mutters the actor John Atkinson in impeccable RP cadence. He continues his soliloquy, delivered in character as the Reverend J. Franklin, an eccentric Church of England vicar. “King Penda. What mystery in this land went down with him forever? What wisdom?” Walking beside Atkinson is teenage actor, Spencer Banks, playing his adopted son Stephen. Behind them, a glowing, orange, sun sets over the Malvern Hills.

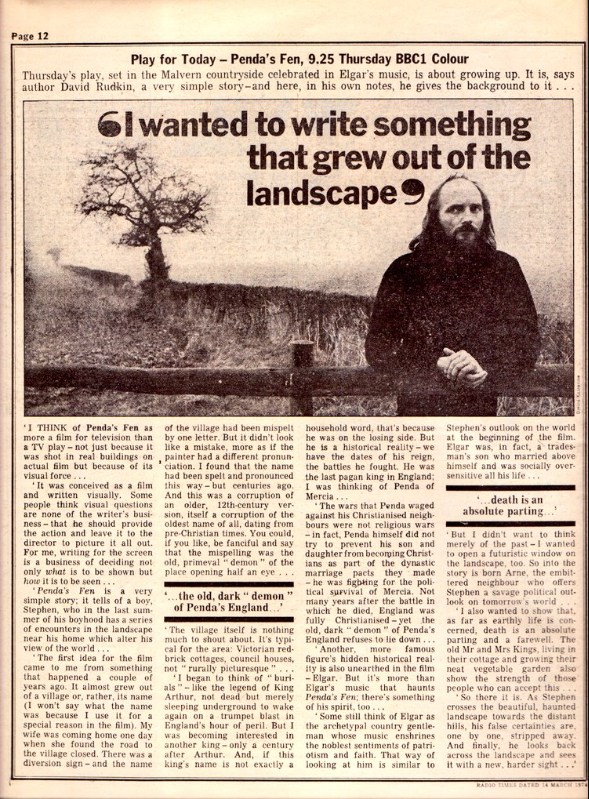

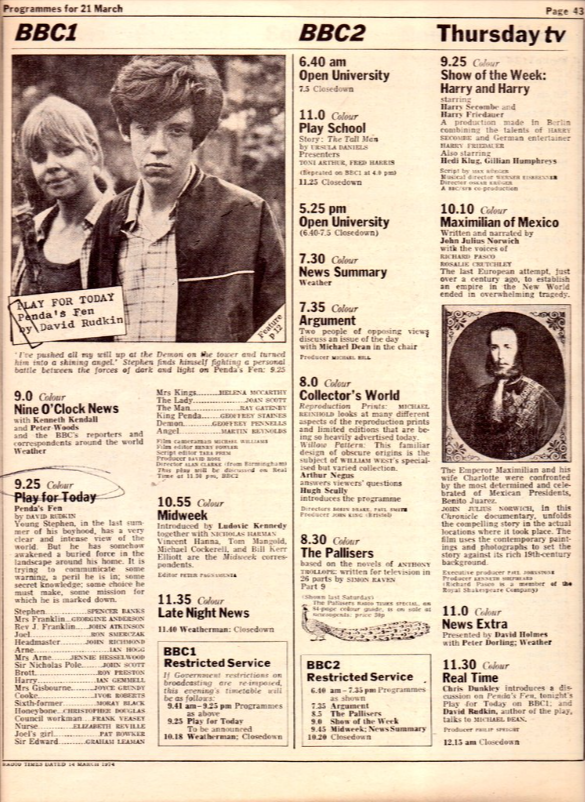

So closes a pivotal scene in director Alan Clarke and playwright David Rudkin’s Penda’s Fen (1974) an increasingly influential cult film produced by Birmingham Pebble Mill’s David Rose, for the BBC’s programming segment Play for Today (1970-1984). In the 51 years since its release, Penda’s Fen has taken on a life of its own, both in the West Midlands, influencing artists, writers and filmmakers to reconnect to their local landscape, but also nationally and internationally, plugging into a flourishing ecosystem of ‘folk horror’ and renewed interest in ‘folkways’ led by major American studios like A24.

Clarke and Rudkin’s production is intimately linked with Birmingham and the West Midlands, summoning the ancient force of King Penda of Mercia, the last pagan ruler in England, who commanded a realm stretching from South Yorkshire to the Cotswolds. Indeed, Clarke and Rudkin’s Penda’s Fen is a rare film that is both explicitly Mercian and West Midlands in identity, celebrating the landscapes of Worcestershire, loathing the suburbs of Birmingham, exploring the legacy of regional artists like Sir Edward Elgar and poet William Langland.

Clarke was an outsider to these mythical resonances, a Wallasey boy working out of London in the realist ‘kitchen-sink’ genre. Instead, it was Rudkin, and his script, that anchored the piece in the region. He grew up in suburban Birmingham, the son of a fire-and-brimstone Northern Irish pastor, attending King Edward’s School and Oxford, before becoming a teacher in the Black Country and Bromsgrove.

His first play, Afore Night Come (1962) made Rudkin’s name as a writer, and depicts an outsider from“Brummagem” travelling to Worcestershire to work as a fruit picker, before descending into madness. Seemingly never attracted by the bright lights of London, Rudkin lives in Pershore in Worcestershire to this day. When I contact him for an interview, he emails me back, writing apologetically that he’s busy and that: “[at 90] I’m racing against the shadow of the Scytheman, to complete my translations of the two Sophocles Oedipus plays from their original.”

Penda’s Fen, which up until recently only had a tiny cult following, has been cited as an influence on major Hollywood directors. For instance, Danny Boyle’s 28 Years Later (2025) is described as a successor to Penda’s Fen in The Telegraph and, indeed, Boyle worked with Alan Clarke on his 1989 Northern Irish piece Elephant, calling his earlier work set in the Midlands “extraordinary.”

In turn, Clarke and Rudkin’s movie has found new resonance with American studio-backed folk-horror pioneers like Robert Eggers (The Witch, The Lighthouse, The Northman). Recently, Eggers picked a book about Penda’s Fen as part of a Le Cinema Club recommendation article. Much of Penda’s Fen’s fascination with paganism and ‘the oldways’ can also be seen in American horror director Ari Aster’s Midsommar (2019). The film also clearly feeds into the work of well-known, arty, English-directors like Mark Jenkin (Enys Men and Bait) and Ben Wheatley (A Field in England and In the Earth).

Penda’s Fen has also connected with a contemporary current of folk-revivalism, often occurring outside London. The music magazine Quietus’s Noel Gardner and journalist John Doran call this ‘the New Weird Britain,’ and to my mind it includes everything from the nature writing of Robert MacFarlane, Helen McDonald and Nan Shepherd; Gen Z’s affection for ‘cottagecore,’ and Zakia Sewell’s radio show.

All this, of course, sits next to the ‘old weird Britain’ being rembraced by younger generations: ancient English traditions like Lewes Bonfire night, wasailling in Herefordshire, cheese rolling in Gloucestershire, and the ball game in Warwickshire’s Atherstone. In a way, Penda’s Fen sits in the middle of all of this — a symbolic centre of an unofficial movement.

A strange coming of age

In short, Penda’s Fen is a coming of age story about the son of an Anglican clergyman, called Stephen who lives between the Malverns and Birmingham in the small village of Pinvin. At the outset of the film, Stephen is an all-too-conventional English public-school boy, straight out of Goodbye, Mr Chips (1969): monarchical, priggish, moralising, and patriotic with an aggressively simplistic understanding of Christianity.

Slowly, over the course of a year, Stephen’s identity unravels. His ethnicity, sexuality, religion, and parentage come apart through a series of supernatural visions influenced by Piers Plowman (1370-86) a medieval poem set in the Malverns. At his public school, based on King Edward's in Birmingham, Stephen is bullied for his earnestness, femininity, and refusal to serve in the cadets. At the same time, his fascination with a childless, married bohemian couple, Mr and Mrs Arne, leads to the revelation that he is adopted.

In the background, two other stories emerge. First, the presence of secret, possibly nuclear, experimentations being undertaken by the military in the area, and, second, the revelation that Stephen’s father, an Anglican vicar, is something of a heretical polytheist deeply engaged with England’s pagan past and ideas from ‘magical’ texts like The White Goddess (1948) and The Golden Bough (1890).

I first watched the film this year, on moving to the West Midlands, but I’ve been haunted by screenshots of the production circulating on social media for a decade: a burnt severed hand looming over the Worcestershire countryside, a terrifying claymation-style succubus sitting on a bed, an androgynous William Blake-inspired golden angel reflected in a lake. Penda’s Fen, despite being incredibly particular to the West Midlands, connected with me deeply as an outsider to the region.

I too was once an awkward, slightly over intellectual, public-school boy, living in a rural landscape dominated by ancient hills (the South Downs not the Malverns) within a family defined by an eccentric dissident clergyman (my grandfather rather than my father). For me, at first viewing, Penda’s Fen was a story about opposing forces: progress and conservatism, the rural and the city, paganism and Christianity, technology and nature, chaos and order.

The richness of Rudkin and Clarke’s movie allows for these kinds of interpretations. Many have read narratives into Penda’s Fen about ecological extinction, queerness, nuclear war and declining birthrates. “Each time I watch Penda’s Fen, it does seem to reveal something new,” says Clive Judd, the owner of Birmingham’s Voce Books and a West Midlands author deeply influenced by Rudkin. “I saw it at the MAC last year and it read very much like a trans text, all the stuff denouncing binary gender constructs.” He adds that: “It can mean differing things depending on your reference point…if I watched it today, I would [have a] heightened sense of its conversation about nationalism…what with the raising of flags.”

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Birmingham vs Mercia

Penda’s Fen is not a particularly sympathetic film when it comes to Birmingham. Rudkin’s script uses the city as a foil, a looming industrial bethmouth, that represents everything wrong with England.

At one point in the story, Stephen’s mother drives him into the south-western suburbs of the city near Longbridge and gives him a stern lecture on his performance at school. The camera zooms in on the mass of Birmingham commuters walking along grey, lifeless motorways, as his mother snaps at him that: “you’ll never get into university, you’ll end up on a conveyor belt…Man is chained to the machine - it's called productivity Stephen, I’ve seen it.”

“Stephen is driven into the dark heart of Birmingham by his mother as a stark warning,” James Machin, editor of Mud and Flame: The Penda’s Fen Source Book tells me. “It’s Tolkien, isn’t it? The Shire vs Mordor. Birmingham, rightly or wrongly, is a big bad over there.” Ian Francis, who organises the city’s Flatpack film festival and has screened the film, concurs: “Birmingham would have been a bit like Mordor for Rudkin, as it was for Tolkien,” he tells me. “A big dirty metropolis on the horizon.”

For Rudkin, it seems, Birmingham represents the mechanical world that he rages against through his character Arne. But the Worcestershire countryside as constituted in 1974 is not much better — in Penda’s Fen it is a relatively new appendage, covering up a hidden pagan past, while distracting itself with class, organised religion, military virtue, and supposed purity. But the conservative idyll of the Worcestershire countryside can’t stop contemporary life creeping in — stagflation, strikes, the tailend of the hippy movement, political unrest, the prospect of nuclear war and uncontainable scientific experimentations.

Importantly, the year in Penda’s Fen is roughly 1973-4, a time when the post-war consensus was breaking up. Just like today, the world of Penda’s Fen is in transition. The historian Dominic Sandbrook has called this period, between 1970 and 1974, a “state of emergency” dominated by “strikes and blackouts, unemployment and inflation” — much like today.

Ian Greaves, the author of Penda’s Fen: Scene by Scene agrees, telling me that: “Rudkin was asked about the term [folk horror] and dismissed it, saying 'it's a bloody political play.' Which I think it is.” Greaves elaborates that Penda’s Fen: “deals with unions, moral pressure groups, pollution, education...all sorts of things that resonated with viewers in 1974 and can still do so today.”

During this time of strife, millions of Brits turned back to the land and heritage. “There was a lot of it about in the early 1970s,” says Francis. “A turn to the rural, a turn to the weirdness in England. This all might be connected to the souring of the 1960s dream.” Indeed, many would start exploring self-sufficiency and communes, while others visited grand country houses and retreated to the conservative shires. “Sometimes folk horror reaffirms conservative things, and sometimes it tears them up,” William Fowler, a curator at the BFI (British Film Institute) national archive says. “Penda’s Fen is doing both.”

In the end, what will save Rudkin’s characters, at least in the world of Penda’s Fen, is Mercia — an older identity hidden beneath more modern notions of Worcestershire, the Midlands and England. For Fowler, Mercia is deeply buried, and part of Rudkin’s mission is to bring it out through the layers of inherited Englishness and Britishness present in Stephen.

One reason Mercia is so buried is that another Saxon kingdom, the southern Wessex, ultimately became predominant. “Wessex has a mythic element to it — but it's familiar, it's been mapped by Thomas Hardy, it's codified and understood,” says Fowler. “But Mercia, if you didn’t know the word already — it could be in the Middle East. It’s less familiar to the English consciousness.” In Francis’s mind, the Saxon kingdom is contrary to official Britishness in Penda’s Fen: “he’s using Merica as a form of resistance.”

A new revival

Penda’s Fen originally aired once in March 1974 on the BBC, then again that same year before disappearing for 17 years until 1991, when it was broadcast on Channel 4. Many young adults in the 1990s remembered it from their childhoods and intentionally taped it — trading video cassette tapes of the film like relics.

“Dedicated enthusiasts then started screening it in art cinemas about 15 years ago,” says Machin, “the first one I heard of was at the Horse Hospital — an arts venue in Bloomsbury.” These arthouse screenings led an unknown person to upload a crackly 1990s video recording of Rudkin’s work to YouTube, spreading the film’s popularity outside of metropolitan circles.

“Its mystique somewhat comes from its scarcity,” says Francis, who has screened the film in Birmingham “It was being exchanged as bootlegs and then a dodgy YouTube upload. It was taking on new dimensions in people’s heads in the absence of not actually being able to watch the thing.”

In 2016 this all changed. The British Film Institute reissued the film on blu-ray — making Rudkin’s work available to the general public for the first time. Since then, Penda’s Fen has influenced a whole host of artists, filmmakers, and musicians. In 2018, researcher Bethany Whalley and musician Ben Walker created a soundscape influenced by the film on BBC Radio 3. There have also been three books published on Penda’s Fen, two of whose authors are interviewed in this piece. Someone has even taken it upon themselves to start making Penda’s Fen figurines. “There’s always a folk revival when things get rough,” Justin Hooper, author of Old Weird Albion, tells me. “Penda’s Fen probably fits into this. It’s about doing. That’s what this current folk revival is about, if anything — getting into the same room with people and doing things together.”

“In terms of contemporary influences you might even need to look to gallery artists to see the biggest impact,” adds William Fowler. My mind immediately jumps to the paintings of Ben Edge and Birmingham-based installation artist Tereza Buskova. Both are full of folklore and folkways — but neither provide the viewer with comfort, or god forbid, tweeness. Both artists also sit uncomfortably at the hinge point between tradition and innovation, reaction and progress.

Whatever reason you watch Penda’s Fen for — the West Midlands connection, its lush evocations of the Malverns, commentary on paganism and Christianity, exploration of sexuality, its portrait of the British middle-classes and private education, its deep concern with technological innovation and runaway scientific-experimentation — there is something to be found in Rudkin’s intense and layered work. As King Penda says, in the last minute of the film: “the flame still flickers in the fen.”

Correction (24/11/2025): the nature writer mentioned above is Robert MacFarlane not "Rupert MacFarlane" as previously stated.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can contact us or visit our advertising page below for more information

Comments