Bartley Green Library is a tiny little thing; a compact, unassuming Edwardian red-brick structure, that looks more like an outbuilding than a beloved community asset. And yet, it’s become one of several key fronts local groups across Birmingham are fighting a mostly unreported battle on.

"People think libraries are just the books,” says John Lines, who represented the area as a councillor for 40 years and is now leading the fight to keep the library open. “But it's not. We've got community organisations, schools and the church who all use it… It has become the hub for people.”

The library — one of thousands funded by steel philanthropist Andrew Carnegie — celebrates its 120th birthday this year, and yet, its future is in great jeopardy, thanks to the knock on effects of Birmingham's bankruptcy.

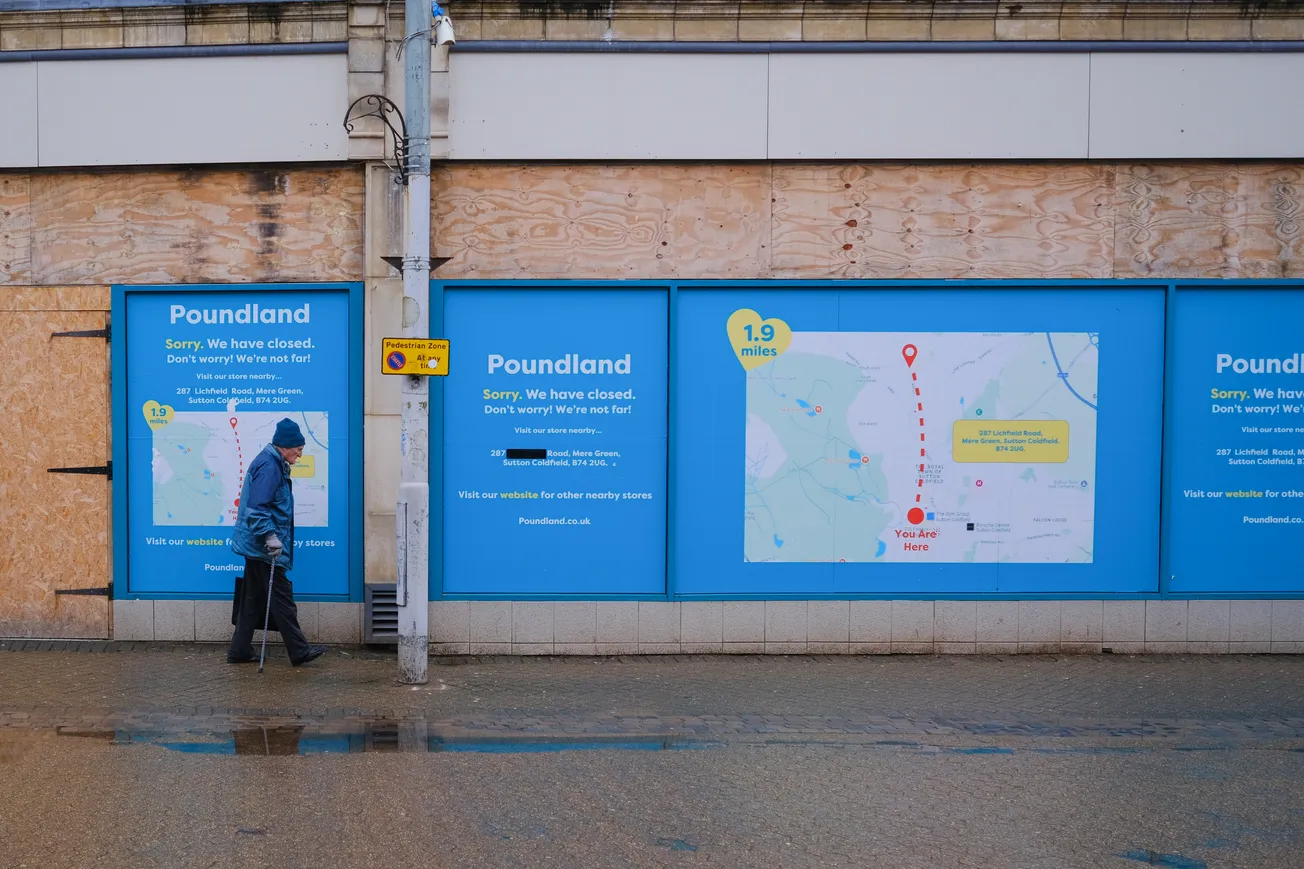

As The Dispatch has previously reported, millions of pounds worth of Birmingham’s public assets are currently being sold off at a fast lick, on the orders of commissioners brought in to try and ‘balance’ the books, after the city effectively declared itself bust in 2023.

And on the chopping block are the likes of community centres in Sutton Coldfield, education hubs in Moseley — and Bartley Green library.

But some locals are not accepting such a fate.

In Bartley Green, Lines says he’s long seen the writing on the wall, even before Birmingham filed a Section 114 notice. “It became obvious in 2017 that the council were going to get rid of our prized asset,” he tells The Dispatch. That year, as library services faced cuts, Lines set up the Bartley Green Community Partnership. He currently chairs the body.

Since then, the partnership have assumed partial management of the library, organising volunteers to support the council-employed librarian on the two days a week it’s open, and paying for maintenance of the ageing building. But last week, they got the news that council funding would be pulled altogether in 2026.

"The building is still alive,” Lines says. We’re speaking as he’s doorknocking in the suburb, collecting signatures in support of turning the partnership into a trust, making it easier to fundraise and apply for grants. "It’s been tough but the commitment from the local community and many volunteers has been nothing short of magnificent.”

This story is for paying subscribers of The Dispatch. If you want to be more informed about your city, and entertained by good old-fashioned storytelling in the process, sign up for a full membership now. You get four editions a week and right now, it's just £2 a week.

In return, you'll get access to our entire back catalogue of members-only journalism, receive all our editions and exclusive news briefings, and be able to come along to our fantastic members' events. Just click that green button below. Sign up below to support local journalism.

Lines says there’s no specific fundraising target, but the main priorities are securing the librarian’s salary, alongside money for maintaining and upgrading the building, which can be a costly business — a recent quote for installing disabled access alone came to around £40,000.

But Lines remains positive due to the strong support from the local community. "It's the people's library, it was given to the people of Bartley Green, and it was the responsibility of the council to maintain it. Well, we can do that as well.”

Last ditch attempts

"At times, it's been plain sailing, at times it's been hearing nothing for three months then suddenly having to do something within a week”.

Over the other side of the city, in Kings Heath, Matthew Powell is diplomatically recounting months of tense negotiations he’s been locked in, as part of a bid to take over the Kings Heath Community Centre from Birmingham City Council. It’s been a long slog of attending interviews, presenting business plans and waiting for answers.

Powell, is a person who quietly gets things done (“Lisa describes me as ‘boring’,” he chuckles). He works for Enjoy Kings Heath, the area’s business improvement district, kickstarted the process back in 2023, along with the aforementioned ‘Lisa’ — local Labour councillor, Lisa Trickett. The idea of a community takeover first emerged as far back as 2018. There was zero movement for years — until Birmingham’s bankruptcy. Then, the administration came knocking.

“The council came back to us as if it was their idea, and said 'we're going to do this now',” Powell smiles, wryly.

Birmingham deserves great journalism. You can help make it happen.

You're halfway there, the rest of the story is behind this paywall. Join the Dispatch for full access to local news that matters, just £8/month.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign In