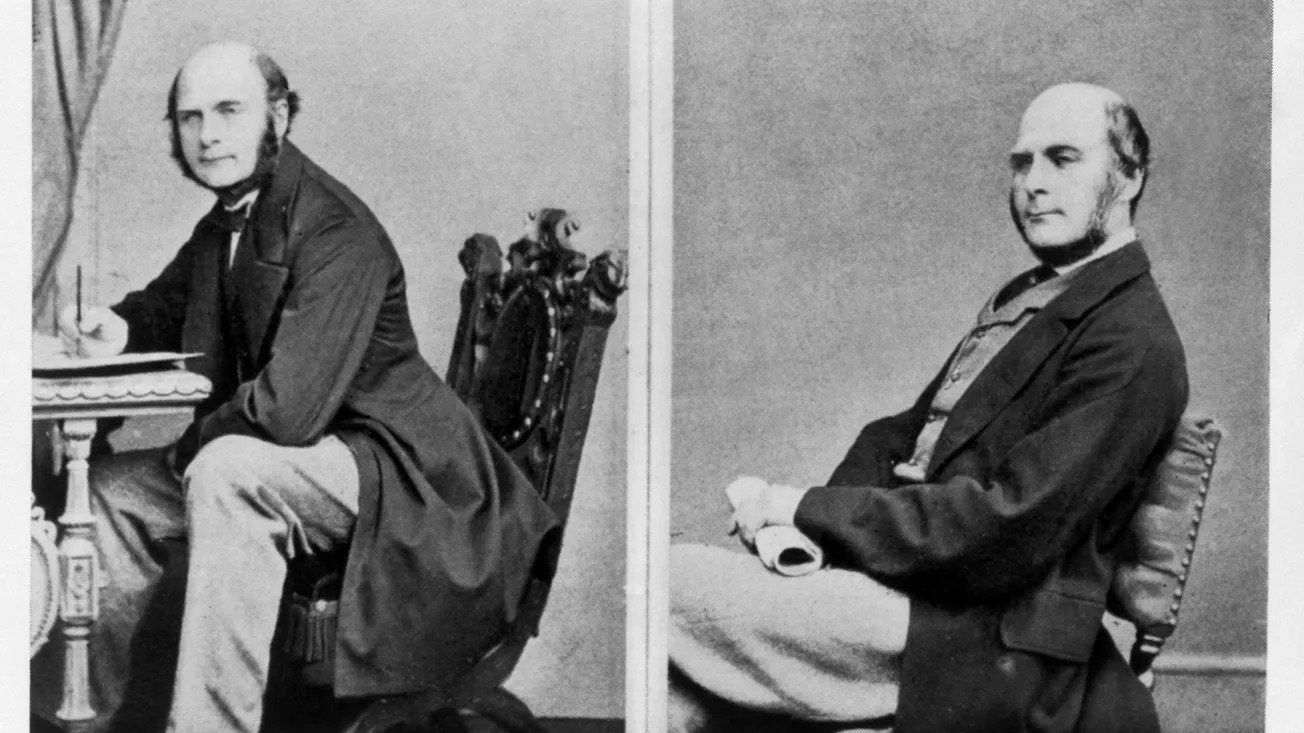

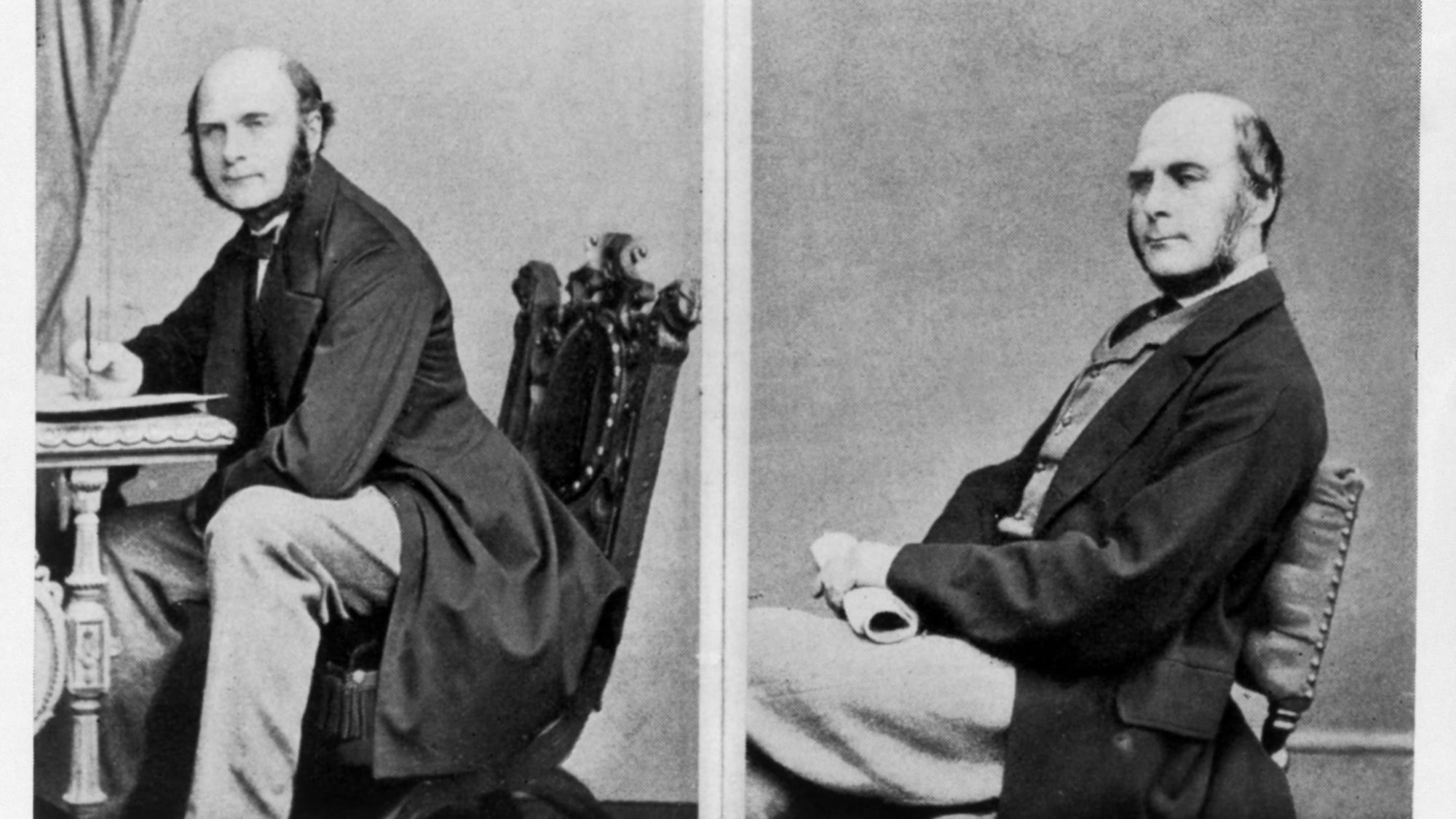

During the uncommonly cold May of 1903, a crowd of important people gathered in a room at London’s School of Economic and Political Science. They were there to hear from the aging, slightly stooped man at the front of the room. As he began to speak, the bright white and bushy mutton chops that made up for the distinct lack of hair on his head, quivered. His address was brief — he couldn’t stand for long periods of time — but what he said had consequences that would reverberate well into the century.

That man was Francis Galton and he was speaking at a meeting of the fledgling Sociological Society. Galton is one of Birmingham’s most influential sons. But unlike other illustrious figures — Joseph Priestley, the Cadburys or Joseph Chamberlain — his legacy is brushed under the carpet.

Why? Because he is the father of eugenics, a pseudoscience that underpins some of the 20th century’s darkest moments, and still dogs us today. Galton was deeply shaped by Birmingham, but he belongs to a strand the city doesn’t like to shout about as much. His family were Quakers, just like the Cadburys, but whereas they made a legacy as chocolate making social reformers (largely shirking their own links to the bloodthirsty British Empire in the process) the Galtons made their money in weapons: selling guns to British colonies.

The Galton family fortune began with Francis’s great-grandfather, Samuel. In the mid 1700s, he married into a family of arms dealers and became a partner in the firm before buying out his in-laws entirely.

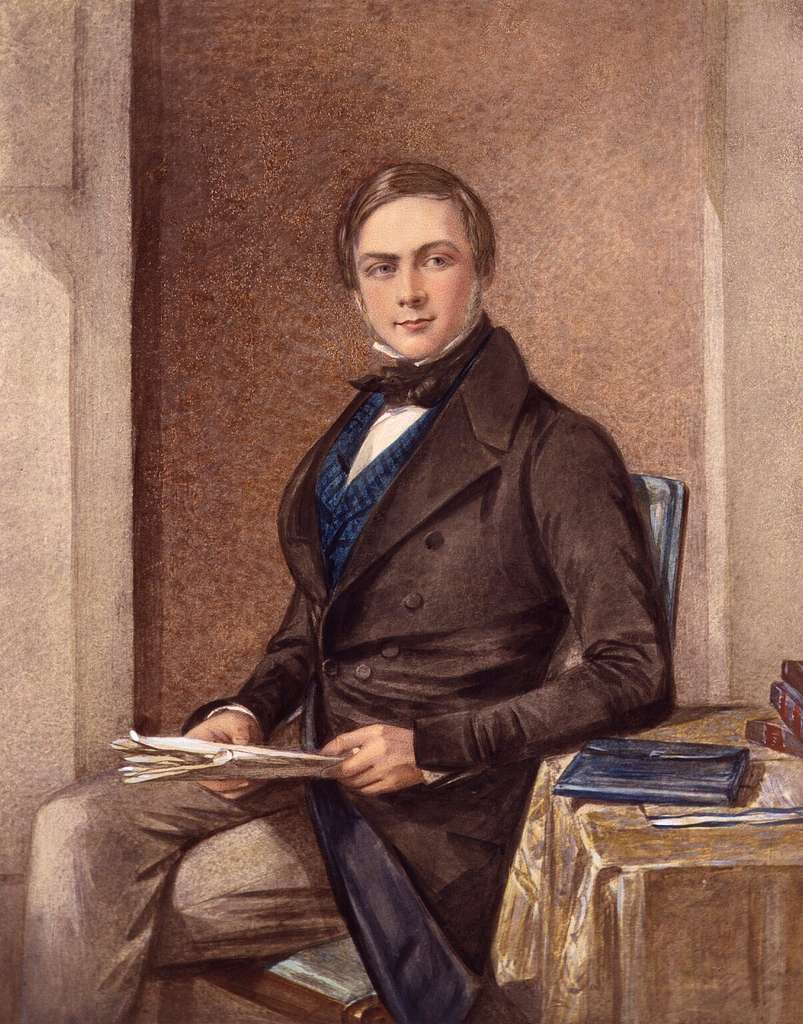

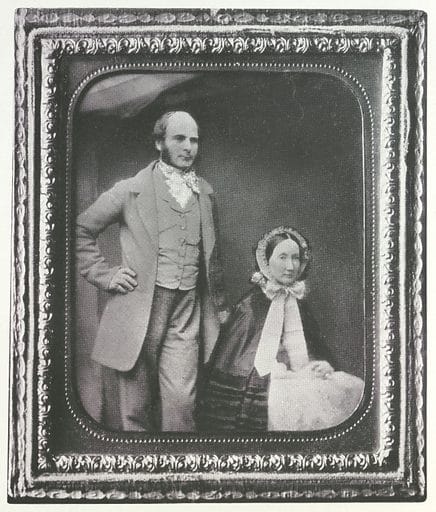

His son, Samuel Galton Jr, was deeply embedded in the Midlands Enlightenment and a founding member of the Lunar Society, the monthly discussion group attended by pioneering intellectuals and industrialists, including Boulton, Priestley and the highly regarded doctor and botanist Erasmus Darwin. This group is how a match between the Darwins and Galtons occurred — in 1807, Galton Jr’s son, Samuel Tertius married Violetta Darwin. The pair had seven children; the baby of the family, Francis Galton, was born on 16 February 1822. He was 13 years younger than his half-cousin, Charles Darwin, who Galton would come to idolise, with terrible consequences.

Galton was born in what was then the fashionable country suburb, Sparkbrook, at ‘The Larches’, a three-storey manor house, named after two huge trees which stood at its entrance. Joseph Priestley had once lived in the same plot, but his home was destroyed in the Birmingham riots of 1791. It was an idyllic place to raise children, with a stable full of ponies for the young Galtons to ride and a brewhouse that had been Priestley’s laboratory.

Young Francis Galton was said to be a child prodigy — his sister, Adele, taught him to read by two and recite The Iliad by six. Despite this, he didn’t enjoy school, especially the years he spent at King Edward’s School where he was often caned. But the institution left a lasting mark on him: it was where Galton had his first encounter with phrenology, the pseudoscientific measuring of skull shapes to ‘determine’ intelligence. An examiner fondled heads of pupils to see if he could predict who would perform well in an upcoming test. He said Galton had “the largest organ of causality” (ability to see the connection between cause and effect) he had ever seen, other than Erasmus Darwin’s.

After leaving school at 16, Galton travelled, then spent a couple of years training to be a doctor at Birmingham General Hospital and King’s College London, but changed course, switching to study maths at Cambridge. Despite his wealthy upbringing, these academically prestigious surroundings were a shock. In his memoirs, Galton would recall becoming “conscious of the power and thoroughness of the work about me, as of a far superior order to anything I had previously witnessed.” In the end, the rigorous study required for the highest degree of honours proved too much for him and Galton suffered a nervous breakdown, writing to his father that reading was making him dizzy. He had heart palpitations and “could not banish obsessing ideas”. In an effort to keep himself focused, he invented a bizarre device called the gumption-reviver, a funnel that dripped water on him whenever he slumped.

However, it wasn’t quite effective enough and his low moods persisted. Deciding to opt for a less challenging degree, he spent much of his final year at balls and dinner parties with his large circle of friends, many of whom were from similarly well established families. Shortly after his graduation, his father died and Francis spent the next six years mooching in West Africa and the Middle East, then returned to Britain to hunt, shoot and live off his inheritance.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

By the mid 1850s he was married and living in London, turning more determinedly to the sciences, writing on meteorology and biometrics. He was obsessed with data collection and measuring the world around him, regularly applying his mathematical mind to eccentric puzzles. He spent three months trying to answer the question: what makes a cup of tea taste the way it does? Twice a day he brewed up using a jerry-rigged pot with a thermometer attached. He recorded the temperature of both the water and the pot, its volume and weight, all the while making notes such as, “very excellent tea (it is true it had cream).”

Galton was an idiosyncratic man with a taste for life’s oddities. He had the time and means to pursue them. The money and connections secured for him by his father, grandfather and great-grandfather meant he was set for life — no need to take on a gruelling job in a factory like many other men of his age or even a more middle class profession, like teaching. He had been born at the heart of the British Empire, at the height of its powers, and raised by the torchbearers of the Enlightenment. Anything was possible.

Yet it wasn't until he was 37 that he found his purpose, after the 1859 publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. The book “made a marked epoch in my own mental development,” Galton gushed. Not just his; Darwin’s work made huge waves, arguing as it did that evolution, not godly creation, was responsible for the natural world. In highly religious Victorian society, many struggled with such a concept. But not Galton. “I felt little difficulty in connection with the Origin of Species but devoured its contents and assimilated them as fast as they were devoured,” he boasted, adding: “a fact which perhaps may be ascribed to an hereditary bent of mind that both its illustrious author and myself have inherited from our common grandfather”.

What Galton felt a particular connection to — evidenced by that nod to Erasmus — was his cousin’s theory of natural selection. Darwin posited that all species share a common ancestor and that each individual animal has differences which distinguish them from their parents. Some of these differences are more advantageous — better camouflage to evade predators, for example — allowing the animal a better chance to survive, to breed and to pass these traits on to their offspring. Over time, they spread through the species, aka evolution.

Galton immediately wanted to apply such a theory to humans, reasoning that the more talented a person was, the more likely they were to have talented relatives. The fact that many of Galton’s own family and friends, who were all from a similar social milieu and were accomplished people reinforced his belief that this was something bred into them. It doesn’t appear to have occurred to him that he was a Victorian nepo-baby, able to take advantage of the best education and opportunities on offer to someone of his class.

Galton devoted himself to this new line of supposedly scientific inquiry. He wrote a book, Hereditary Genius, published in 1869, concluding that his theory was right: genius breeds genius. Darwin was impressed. Writing to “Dear Galton” even before he had made it through the first 50 pages, his cousin exclaimed “I do not think I ever in all my life read anything more interesting and original--and how Well and clearly you put every point!”

Galton built on this work in his 1883 book, Inquiries into Human Faculty. There he argued that instead of letting nature run its course, man should intervene to ensure survival of the fittest, arguing the people with more desirable traits ought to make more desirable babies. Here, he first introduced the term eugenics from the Greek eugene, meaning ‘good breeding.’ Eugenics in one form or another long predated Galton but he made it seem scientific, at a time when science was exciting and was beckoning in the modern age.

Yet Galton’s approach wasn’t exactly rigorous. He was trying to assess vague qualities like ‘genius’ and ‘feeble mindedness’ which are difficult to quantify. “Galton’s particular contribution,” the historian Professor Philippa Levine has told the BBC, “is this principle of bringing together the quantification on the one hand and the dream of improving the human race on the other. When you put those two together you get the explosion of eugenics.”

In the course of his work he made significant developments, particularly in the fields of statistics, where he developed the concepts of standard deviation and correlation. He also took substantial credit for advances in fingerprinting as a means to identify people, which had huge implications for the burgeoning field of criminology and resulted in Scotland Yard adopting the practice. That said, it did upset one of the pioneers of the field, Henry Fauld, whose ideas Galton had enthusiastically used without proper citation in his 1892 book Finger Prints. Faulds became so frustrated that he even challenged Galton to a bare-knuckle fight — the eugenicist declined.

Between 1901 and 1908, eugenics was rapidly legitimised by academia and the political classes. The historian Dr Nathaniel Adam Tobias Coleman (they strike through their last name because it was given to their ancestors when they were purchased from Jamaica) has argued that it was helped along by three key factors. The first was Galton’s vast Brummie wealth which he used to found the Galton Laboratory for National Eugenics and professorship at University College London (UCL) and a new scientific journal. The second was the fact that British society was already organised around a rigid system of social rank — white Europeans considered themselves superior to the peoples they colonised and Galton was no different. As he wrote of the Nama tribesmen he encountered in his 1853 travel book Tropical South Africa: “Some had trousers, some had coats of skin, and they clicked, and howled, and chattered, and behaved like baboons…I looked on these fellows as a sort of link to civilisation.”

The third and final component was a sense of crisis, triggered by Britain’s flailing performance in the Boer War in 1899-1902. British troops were losing to native Africans — an unthinkable notion for imperialists — and in 1901, three out of five military volunteers were rejected because they were too unfit. What’s more, the birth rate was declining. As the upper classes wrung their hands over the potential decline of the British Empire, Galton’s ideas about how to “improve the race” looked appealing.

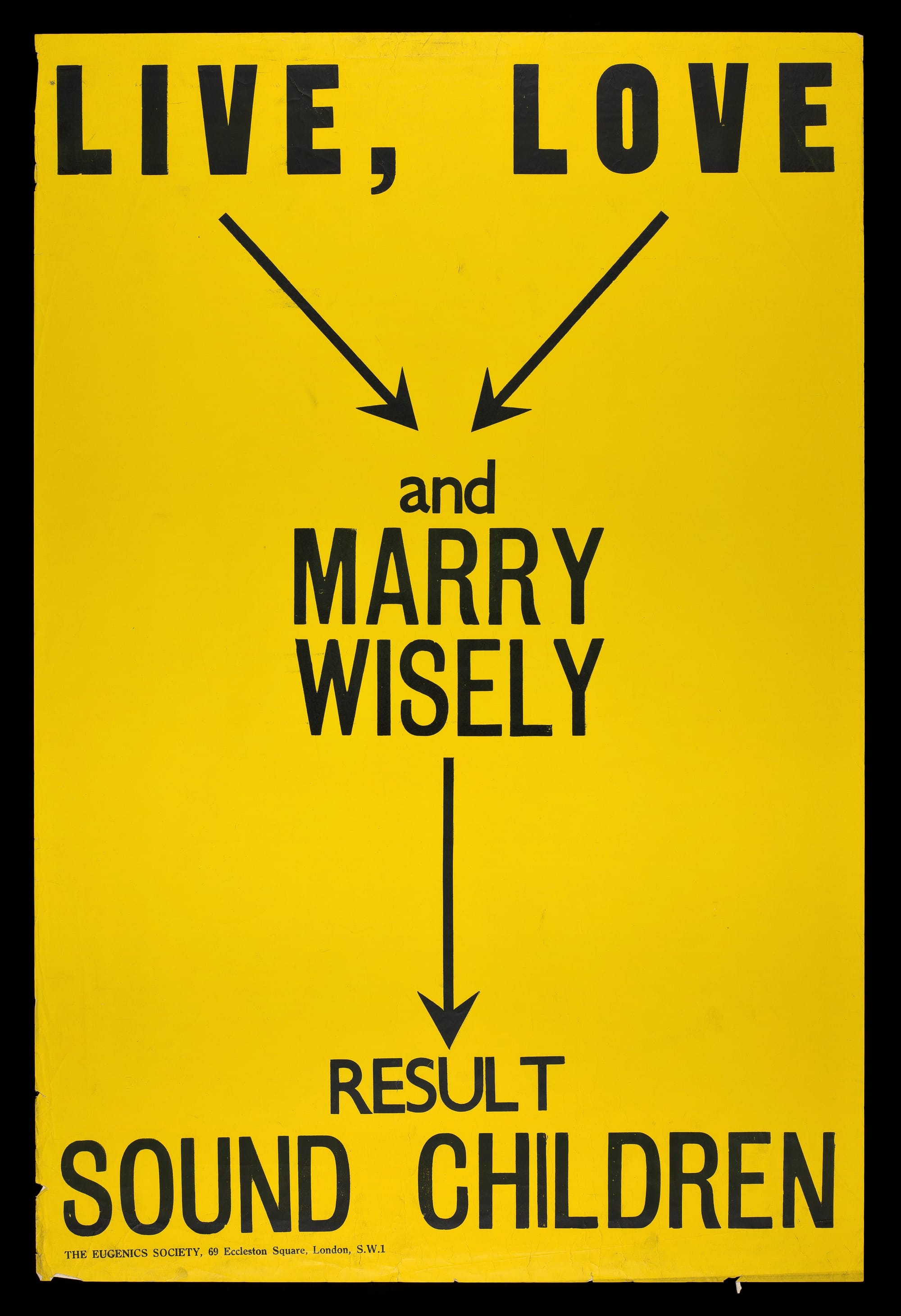

The British urban population had grown significantly during a century of industrialisation, many of whom were desperately poor and living in cramped and unsanitary conditions, which concerned the middle classes who set up various charities to address social issues related to poverty. In 1907, Sybil Gotto founded the Eugenics Education Society in this tradition, based on the belief that poverty was a result of inherited defects, and used it as a vehicle to try to stop poor people from having babies.

Galton died in 1911 — he’s buried in the village of Claverdon in Warwickshire. After his death, interest in eugenics became widespread and it was soon embraced by countries around the world, with sinister results. In many countries, states seized upon the opportunity to control people and reproductive rights as a way of purging those deemed undesirable, enthusiastically legislating for the enforced sterilisation of tens of thousands of citizens. According to Dr Adam Rutherford at UCL, more than 30 countries had eugenics policies for most of the 20th century. In 1912, Britain narrowly avoided passing a bill to sterilise the “feeble minded”. The ultimate enactment of eugenics ideology, of course, occurred in Germany under the Third Reich.

After the horrors of the Holocaust were revealed, eugenics fell from favour almost overnight. Eugenicists of this era had claimed science, especially genetics, as “its backbone,” says Rutherford in a video for UCL. But their “grasp of the complexities of genetics was slight and superficial and in many cases just plain wrong.”

Many of the more progressive changes that came from early 20th century reform remain in Britain: access to birth control and public health services to name a couple. But while its tempting to think that the sinister lure of eugenics has been banished, the paranoia associated with it lingers on in conspiracies like the Great Replacement Theory.

Galton wasn’t solely responsible for the horrors that came about in the wake of his death. But the rich boy from Birmingham had unleashed something on the world that could not be put back in its box — and still haunts us to this day.

Comments