🎁 Want to give something thoughtful, local and completely sustainable this Christmas? Buy them a heavily discounted gift subscription. Every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to Birmingham — a gift that keeps on giving all year round.

You can get 38% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

Dear readers — ‘The ramp’ on New Street has achieved cult status in Birmingham. A well known meeting spot for frazzled shoppers, mooching teenagers, and just about anyone in need of an easy-to-spot landmark, this unremarkable walkway has made its way into the local, collective imagination. It is affectionately printed on posters, postcards, and postmodern tea towels, a tribute to one of the everyday quirks of life in the second city.

But what about its past lives? In today’s story, regular history writer Jon Neale takes us back in time to the grand old days when an architectural jewel stood in place of the ramp we know and love today. The evolution of this iconic spot tells a story about Birmingham’s obsession with demolishing and rebuilding its past. But before that, your Brum in Brief.

Brum in Brief

❓ We’ve been doing some more digging into Councillor Akhlaq Ahmed, the Labour member for Hall Green North who has a reputation for absenteeism. To jog your memory, Councillor Ahmed has a rather poor attendance record having attended only about half the number of council meetings expected of him since he was elected three years ago. Residents also reported that he has a habit of ignoring emails and casework. It turns out, he hasn’t been much better at making it to his own, monthly advice surgeries for residents. When The Dispatch popped to Tyseley Community Centre in early December (according to the council website, Ahmed hosts his surgery there on the first Friday of every month) he was nowhere to be seen. A private event was underway and the person running it had no idea who Ahmed was. When we called Ahmed to check, he hung up on us before we could get an answer. When we rang the community centre a few days later, the manager checked their records and confirmed Councillor Ahmed hasn’t held a surgery there for five months.

But that’s not all: we aren’t sure Ahmed is even living in Birmingham permanently, despite the fact that Labour has chosen him to stand in next year’s local elections here. Our investigations show that Councillor Ahmed is linked to three properties: a commercial property each in London and Birmingham, and a house in Tysley which is owned by his wife Tehseen. It’s this address where Ahmed is listed on the electoral register. But when we paid a visit two weeks ago, it wasn’t Ahmed or a member of his family who answered the door, but a young man who didn’t recognise Ahmed’s name. This tenant told us it was a “shared house” that had been rented out for about a year. So where does Councillor Ahmed actually live? The Dispatch understands that he has confirmed to Labour West Midlands that his primary address is in Birmingham and the party has seen no evidence to suggest otherwise. However, all the evidence The Dispatch has gathered tells a different story. Do you know where Councillor Ahmed lives? Is your local councillor hard to reach? Get in touch: editor@birminghamdispatch.co.uk

🚮 A striking bin worker has become the first lorry driver to lose his job since the long-running refuse dispute with Birmingham City Council began. George Wilson says he refused to accept a £7,000 pay cut and must now scale back his family’s Christmas plans. The 60-year-old had been in the full-time role since 2015 and had expected to retire from it: “I would have carried on until I was 67,” he said. “I didn’t want to leave. It was a really good job.” The council, however, said all drivers were offered a variety of options including retraining and voluntary redundancy. ‘Three individuals refused to engage with this process and as a result were subject to compulsory redundancy,’ a spokesperson said. (ITV).

💼 A woman is calling for records of people who grew up in care to be handled more sensitively. Nine years ago, a social worker handed 50-year-old Jackie McCartney “an old battered brown box” containing all the details from her childhood. (BBC).

Today, we step back in time to discover the past lives of iconic city centre spot, 'the ramp'.

Arriving at New Street Station in the mid-1930s provided a very different experience to today. The noise of steam engines and the scent of smoke in the air was inescapable — but there was also a genuine sense of grandeur to the surroundings.

Looking up, you would see a vast expanse of glass — the largest single-span glass roof in the world at the time of opening in 1851. It was as long as two-and-a-half football pitches and 15 feet higher than the Town Hall. That much was to be expected given its maker, Fox, Henderson & Co, had been responsible for constructing London’s world famous Crystal Palace.

Exiting via the main route out onto Stephenson Street, the splendour was sustained at the front, where the six storey, Italian-style Queen’s Hotel which was designed by William Livock and built in 1854, joined up with the station.

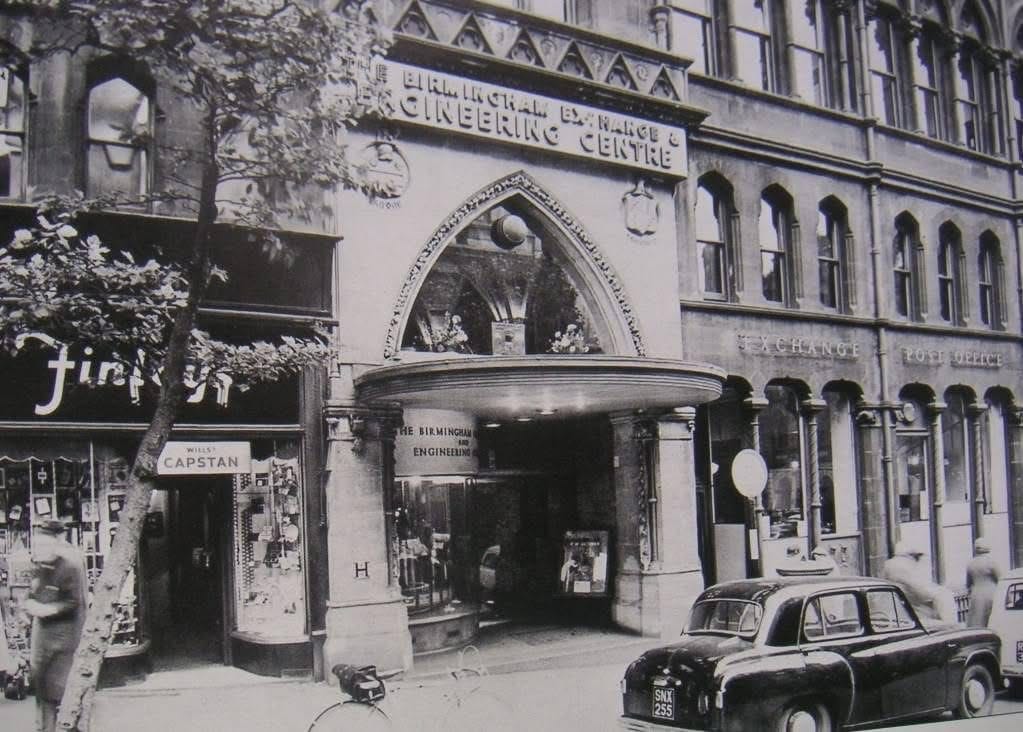

A time traveller from today would recognise the elegant Midland Bank HQ opposite – now the Apple Store – as well as Piccadilly Arcade and the buildings opposite on Corporation Street. But the most jarring difference would be just to the right. In the place of the beloved ‘ramp’, there was one of the city’s grandest gothic revival edifices – the Exchange.

Its name came from its role as the central commodity exchange for the West Midlands metal industries, although this was just one of its functions. This six-storey building had a cavernous 23-foot ground floor and measured over 180 feet from the base on Stephenson Place to the tower at its top, almost twice as high as the Council House dome. But as the ground rose steeply to New Street, the frontage there was more modest. Inside, there was a large hall and an assembly room designed for balls, concerts and the like.

It also contained the city’s first telephone exchange, the original headquarters of the Chamber of Commerce, and a Masonic Hall, alongside other offices. Restaurants and ‘lounges’ were scattered throughout.

It had originally been built in 1865 to the plans of local architect Edward Holmes. A decade later J.A. Chatwin – responsible for much of Victorian Colmore Row and what is now the Old Joint Stock pub – provided designs that doubled its size.

There was a 21ft high arched entrance to Stephenson Place and a row of shops that continued on New Street, where it adjoined another neo-gothic gem: The King Edward’s Grammar School. Built in 1838 to designs by Charles Barry and Augustus Pugin, it became a prototype for their later collaboration on the Houses of Parliament. This bordered, in turn, the seven-storey “Venetian Gothic” Arden Hotel. Further down, to the left, was the tall entrance to a complex of ornate arcades, the City and Midland.

But there were already clues as to why all these buildings would shortly vanish.

Unlike the obvious peers, Brum was booming in these inter-war years as a result of its new industries: electrical engineering, motor manufacturing. And all that employment and spending power meant that these shopping streets were far more packed almost anywhere else in the country.

But the centre was simply too concentrated for what had rapidly become the country’s most important and affluent big city outside London. The crowds were so dense that police-controlled, one-way walking routes were set up to prevent ‘pedestrian jams’.

Mass car ownership had already become a reality here when it was still a luxury in most of the country. The resulting traffic jams were already notorious, despite the introduction of Britain’s first large-scale one-way system, which completely baffled outsiders.

Officials had been hard at work since the 1920s to find solutions. Their vision was one of expansion: a new Art Deco civic quarter around Broad Street, and the country’s first ring road, albeit based on shop-lined boulevards not motorways. But only Baskerville House and the Hall of Memory emerged before war broke out in 1939.

After the war, say in 1960, the scene at New Street was dramatically different. The roof had vanished, destroyed in the blitz. Platforms and footbridges had also been damaged, and it had all been temporarily patched up. Outside, though, the Exchange still stood, albeit grimy and tired-looking.

But the crowds outside were bigger and more cashed-up than ever. Alongside manufacturing, Birmingham’s services sector – banking, insurance and the like – was now expanding just as rapidly. The main streets had a higher retail spend per square foot than the West End.

Developers had taken notice of the demand for modern retail and office space. Birmingham had become, by some margin, the main provincial centre of the mid-century commercial property boom. Even before the council began large-scale demolition, old buildings all over the city were being replaced by new office blocks and shops at a pace unrivalled outside London.

The grammar school had been first to go, in 1937. In its place were two buildings – the Paramount Theatre, later an Odeon, and the Portland Stone King Edward’s House office block, built by local entrepreneur Jack Cotton, who had been to school on the site. The Arden Hotel next door was awaiting demolition.

Cotton would later make his mark internationally, but at this time he was still busying himself in Birmingham. Further down New Street, where the arcades had been flattened by the Luftwaffe (except for the tiny remnant off Union Street), he was building Birmingham’s first purpose-built shopping centre. It was named ‘the big top’ as the site had been used for a circus after the war.

Unsurprisingly, the traffic jams were worse than ever. Something needed to be done, particularly as it might continue to get much, much worse – central government’s plans for motorways had many of them converging on the city.

Every city had a plan for comprehensive redevelopment, and few had qualms demolishing Victorian buildings, the vestiges of an exploitative, squalid era best consigned to history. But few had Birmingham’s head start, its affluence, its attraction for developers, or the confidence produced by its then recent history of leading the country in civic reform.

Nor did they have a figure as implacable and all-powerful as Herbert John Baptista Manzoni. Installed as city engineer in 1935, Manzoni saw himself in the tradition of Chamberlain, reshaping the city for the future for the benefit of its citizens. Unfortunately, he translated that as making Birmingham fit for the modern motor age; everything else was a sentimental distraction.

He had already formalised the pre-war plans for shop-lined boulevards in the 1946 Birmingham Development Plan, which would see New Street’s roof rebuilt and the entrance reorientated to the new road. But by 1960 he was frustrated; only a small section had opened, today’s Smallbrook Queensway, onto an area where wartime destruction had been severe.

While Birmingham had been the second most bombed city outside London, damage was diffuse. As a result, it had not received the government attention given to levelled centres such as Coventry.

But the government was introducing a new form of subsidies: for full-on high speed urban motorways. These were the core of the new development plan, published in 1960; pedestrian routes would run above or below via subways, not alongside the traffic as in the earlier boulevard vision.

The remaining gap in the funding could be fuelled by a radical idea – selling off cleared land around the ring road. The plans were indicative; Manzoni disliked the idea of more detailed prescriptions, as it might slow progress. Giving developers relatively free rein would be far faster.

The most obvious candidate for this process was the vast and bomb-damaged Bull Ring. This would be replaced by a monolithic shopping centre which also formed part of the ring road structure. Work began on it in 1961; the damaged Victorian market hall, which the 1946 plan had also depicted as rebuilt, was swept away.

The new plan also envisaged New Street Station, a key site in the heart of the city, being completely redeveloped. British Rail, which owned the site, wanted to modernise the West Coast Main Line, but lacked funds. These could be provided by a similar process to the Bull Ring. The old station and hotel could be demolished and a concrete deck built over the platform.

The ‘air rights’ (permission to add stories on top of the existing building) could be sold off for development. In due course, an office block and the Birmingham Shopping Centre (later the Pallasades) emerged on top of the old platforms, in a joint venture that included Jack Cotton. This all immediately doomed the old frontage and the Queen’s Hotel, which came down in 1964.

But people had to be encouraged directly through the new shopping centre, which was on a level with New Street itself, and on to the connected Bull Ring. It certainly wouldn’t do to have them exiting at platform and street level onto Stephenson Street – two floors below – avoiding spending opportunities. Meanwhile, keen shoppers on New Street might baulk at walking down Stephenson Place and then up stairs or escalators to the new centre.

There needed to be level pedestrian access from New Street, and the idea of the ramp was born. But Stephenson Place was not wide enough for that – something would have to give: the Exchange.

Manzoni had retired in the early 1960s, but his disdain for old buildings had pervaded the council. The vast structure came down a year after the station itself and was partly replaced by the ramp.

During demolition, a glass bottle ‘time capsule’ was found beneath the foundation stone. It contained newspapers, coins and plans of the building; wine and oil had apparently been poured over it in what may have been a masonic ritual carried out at the time of construction in 1865.

On what was left of the site, a new office building arose, again built by the omnipresent Jack Cotton but this time in classic 60s slab-and-podium style. Its name: the Exchange Buildings.

During the same year, central government extended its ban on new office development in London to Birmingham. While this might have undermined the city’s economy, it did have the side effect of saving the set of Victorian buildings opposite, at the junction with Corporation Street, where another redevelopment had been proposed.

The ring road was finally completed in 1971, with swathes of the city’s 19th century fabric razed as a result. This destruction did finally produce a reaction, with a campaign succeeding in preventing the demolition of Victoria Square and Colmore Row outlined in the 1970 plan.

British Rail did manage to carry out one more demolition. With New Street now the main terminus following electrification, Snow Hill was closed in 1972 and demolished in 1977.

If the Exchange had been in another city, it might have remained half-empty and crumbling, until being reinvented in the late eighties or nineties when Victorian architecture became more fashionable.

It was not as if other cities did not have similar intentions. In Liverpool, the infamous Shankland plan envisaged much of today’s centre being almost entirely replaced by new buildings surrounded by a motorway-like ring road on stilts.

Manchester had plans that envisaged a dual carriageway ring road and the demolition of much of what makes that city distinctive today.

But the affluence and confidence in Birmingham meant that of all English cities, only it had the conditions to realise such plans. Even Leeds, which shared some post-war prosperity and was a distant second in the commercial property boom stakes, could only half-rebuild itself as the ‘Motorway City of the Seventies’.

As the late architectural critic Gavin Stamp says in Britain’s Lost Cities, “Birmingham’s transformation was not born so much of the self-hatred and disgust with the past that afflicted most of the great Victorian cities of Britain, rather from optimism and vigour. As it had been in the past, Birmingham was to be the city of the future. In easy retrospect, it is sad that that optimism was so misguided.”

The ramp, one of the myopic by-products of the rush towards that vision, has since gained totemic status, partly because it’s such a convenient meeting place. It adorns tongue-in-cheek postcards and was recently designated as one of the city’s icons by Joe Lycett. It’s ironic, Brummie self-deprecation distilled.

But ultimately it’s a commercial manoeuvre aimed at maximising funding for infrastructure elsewhere, a patching up in the absence of better ideas. It creates a jarring contrast with New Street itself, which up to Victoria Square does a rare thing for an English city by having the scale and elegance of the main street of a regional capital.

It’s easy to mourn lost buildings, especially grand ones like the Exchange, and forget the grime and draughtiness old pictures don’t capture. They also replaced an older, Georgian Birmingham.

The question for me is why, in this later rebuilding, it was replaced with something so dramatically underwhelming, why the entrance to the city became so cheap-and-cheerful in comparison to its earlier incarnation.

The deeper issue is whether Manzoni’s obsession with iconic engineering – and his blindness towards detail and ground-level experiences – still persists in the city today.

🎁 Want to give something thoughtful, local and completely sustainable this Christmas? Buy them a heavily discounted gift subscription. Every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to Birmingham — a gift that keeps on giving all year round.

You can get 38% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

17/12/2025 correction: an earlier version of this article referred to Piccadilly Circus instead of Piccadilly Arcade. This has been corrected.

Comments