On an unassuming brick wall in an underpass overshadowed by Snow Hill railway bridge is an historical plaque erected in 2008 by the Birmingham Civic Society. The text commemorates a grisly piece of the city’s history:

Near this site, at what was then the junction of Great Charles Street, Snow Hill and Bath Street, Philip Matsell, aged 30, was hanged at 1.25pm on Friday 22nd August 1806 in front of a crowd estimated at 40,000. He had been convicted of the murder of Robert Twyford, a "peace officer" (a parish constable or watchman - the precursor of the later Police Officer) on that very spot and was buried in St Philip's Churchyard.

Birmingham in 1806 was a remarkably different place to the million-strong city of today — its population a mere 70,000. The last bull had been baited in the Bull Ring eight years prior and the recently completed canal to Warwick had opened new trade routes to the city. Like every other major metropolis, crime was apparently rife. “Robberies and burglaries were of frequent occurrence… Predatory bands scoured the roads in every direction, and did not hesitate to attack the equipages of travellers,” wrote historian Robert K Dent in 1880. The inhabitants of Birmingham were at the mercy of the night. There were no public street lights and instead communities relied on lit braziers, lanterns and surveillance by peace officers.

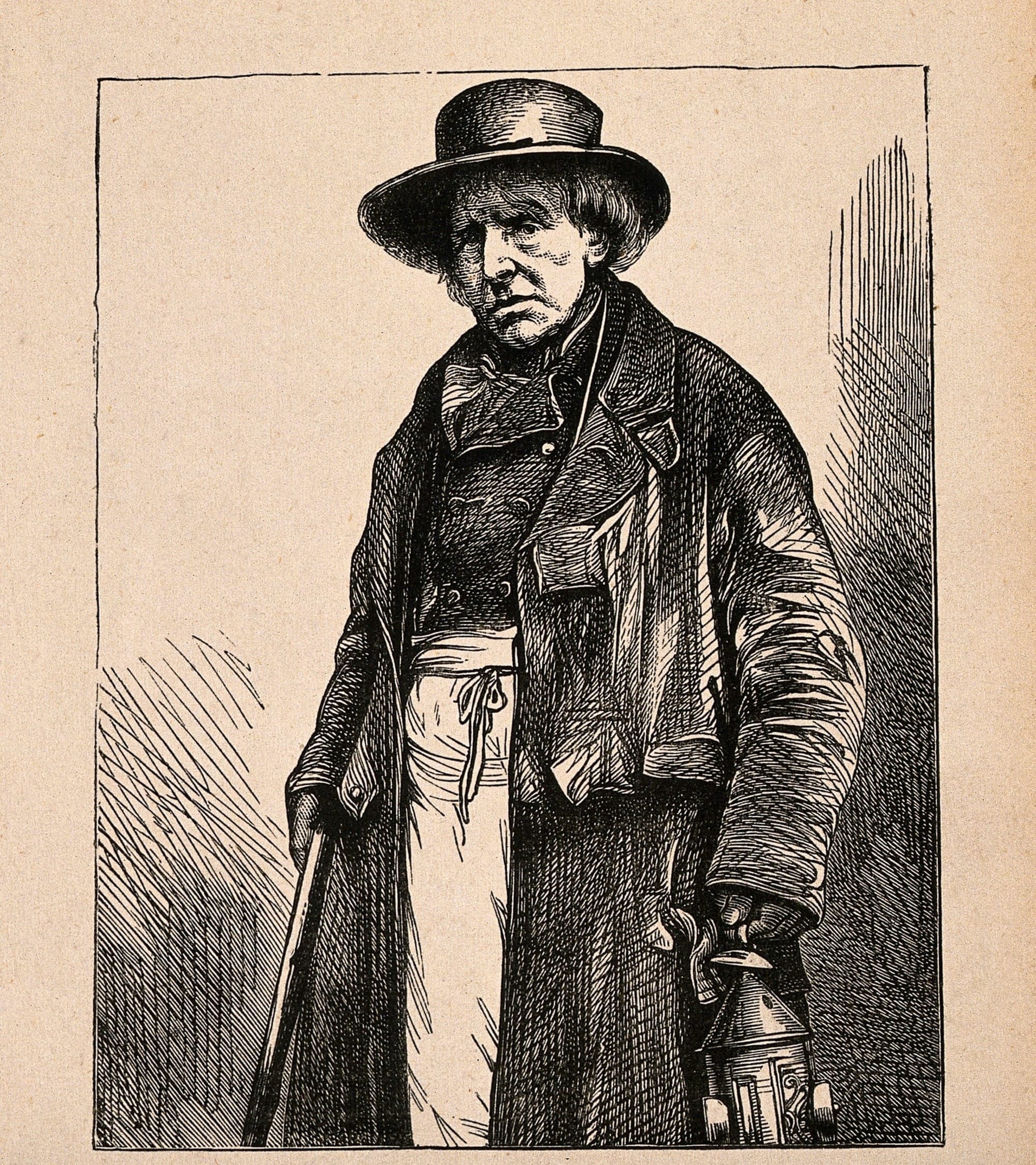

One such watchman was 46-year-old Robert Twyford, who lived with his wife and five children on Whittall Street in the city centre. The exact date is contested but, one midnight in early July 1806, Twyford was stationed in Snow Hill. In modern Birmingham, 12am echoes with the hum of stumbling students and the whine of cars on the Queensway. In 1806, the night air would have been filled with the sound of late-night carriages and the whinnies of stabled horses. Watchmen were commonly armed with a wooden staff for defence and a lantern to cut through the dark.

According to one newspaper at the time, as Twyford patrolled, he was “informed that some suspicious characters were lurking about his round”. As he rounded the corner of Bath Street and Great Charles Street he came across a gang of men. As he approached, one of them fired a shot.

The lead ball entered Twyford’s left breast, travelling through his lungs and lodging in his right shoulder. He collapsed; the group fled. Six weeks later, a man was hanged.

That man was Philip Matsell, and popular history has long cited him as the only person to be publicly put to death in Birmingham — for murdering Twyford. But neither claim is true. His was the final, but by no means the only, public hanging in Birmingham. And he was not hanged for murder. In fact, when Matsell was executed, his victim wasn’t even dead. This is the real story.

In 1806 Birmingham didn’t have its own criminal court. Local convicts were tried and sentenced in Warwick. Those sentenced to death were commonly hanged on Gibbet Hill in Stoneleigh, Warwickshire, and it’s perhaps this that has led to the erroneous claim that Birmingham felons were not publicly executed in the city. In fact, there are multiple recorded examples.

Matsell was certainly the last man to be publicly executed in the city, and, before his capture, the public was clamouring for blood. The victim had been taken to the hospital, where the lead ball was extracted by surgeon Dr George Freer, but the press was not optimistic about Twyford’s hopes of recovery. Articles referred to the anonymous assailant as a “murderer”, and demanded justice. Aris’s Birmingham Gazette advertised two rewards for information leading to a conviction (one reward of 50 pounds is roughly equivalent to £4,000 today). These bounties would rise incrementally.

According to the same publication, “the villain that shot the said Robert Twyford stands five feet nine inches high, about 21 years of age, had on a light coloured thin summer coat, white stockings, [and] a coloured handkerchief round his neck.” Meanwhile, The Sun newspaper described the shooter as being 37 years old and five feet nine inches tall, with a green shade over his eyes. We don’t know what Matsell looked like for certain, but according to census data, he was born in Great Yarmouth in 1776, making him around 30 at the time.

Matsell had lived a colourful life. He had joined the British Navy in his adolescence, serving for several years before leaving to find work ashore. It's often claimed that he became an apprentice to a London surgeon; however, like many details surrounding the case, this appears to be a long-standing misinterpretation. In reality, Matsell was employed by a man named Mr Barber, leading later journalists to assume, mistakenly, that he had worked for a barber-surgeon. Actually, his employer was a maker of metal trinkets (known as a toymaker). At some point, Matsell turned to crime, and was imprisoned in London for stealing 26 pieces of silk and woollen cloth from a shop. After his release, he resurfaced in Birmingham, where he began operating with a gang of petty criminals. It was there he reportedly adopted the alias of “Drake”.

There is no record of how Matsell was identified as the perpetrator of the Twyford shooting, but thanks to the sizeable reward and an offer of the King’s pardon to any accomplices with information, he was eventually apprehended and swiftly sent to trial. On 19 August 1806, he stood in the dock at Old Shire Hall Court in Warwick to protest his innocence.

The defendant was one of five accused men to stand trial that day: his peers were two forgers, a horse thief, and a rapist. These courts, known as ‘assizes’ and dealing only with the most serious crimes, were overseen by a senior judge who travelled a circuit from London to the provinces. Presiding over the proceedings that day was the distinguished Sir Giles Rooke, who, sadly for Matsell, was not in an amiable mood that day. Rooke condemned him as a man who “possessed a wicked and malicious heart”, on account of his perceived remorselessness, and told Matsell he was to “hang by the neck, until your body be dead, dead, dead”. To make matters even more chilling, he was sentenced to be executed on the very spot where the crime had been committed.

At 7.30am on 22 August 1806, Matsell waited in confinement in the Warwick gaol. Through the walls he may have heard the spluttering and riotous cheer as two forgers, Robarthan and Caddick, were hanged outside. One hour later, Matsell began his final journey to Birmingham to meet the same fate, escorted by high sheriffs, Mr Laugharne (a clergyman), and Mr Tattenhall (the chief jailor of Warwick and most likely the executioner). As the convoy arrived in Knowle for a brief respite, Matsell was given several cups of wine. The grim parade then continued to Sparkbrook where the condemned man (understandably) drank even more. From there he was joined by mounted soldiers, loaded onto an open cart (draped in black cloth), and introduced to a fellow passenger: his own coffin.

By 1pm, the crowd swelled as the procession wound its way from Camp Hill, threading the narrow streets of Deritend, before pressing on to Snow Hill and Great Charles Street. Matsell was returned to the scene of the crime, where a temporary gallows had been constructed, wooden beams reaching towards the sky.

Church bells knelled, shops closed their doors, and a reported crowd of 40,000 gathered — more than half of Birmingham’s population at the time. Accounts of hangings are often sensationalised; the condemned join the pantheon of beguiling villains that had swung before. Nearly 80 years later, Robert K Dent described the scene: “Some [of the crowd were] sobbing hysterically at the unusual sight, some jeering and shouting, and some curs-ing; and, as it seemed, only one man in the vast crowd calm and collected, and that one the culprit himself.”

He recounts how Matsell rejected a clergyman’s offer to pray and refused all aid in mounting the ladder. “Clenching his hands together, bound as they were, with a ‘Here goes!’ he leaped in the air.” Dent wasn’t there, but despite the potentially apocryphal reports we can be sure of one thing: Matsell was successfully — and publicly — hanged for the shooting of Robert Twyford.

The victim survived the shot – but he was unable to work and his family risked destitution. About a week after the hanging, Aris’ Birmingham Gazette announced a contributable fund “as a reward for [Twyford]’s honesty, diligence, and courage … and to relieve a large family deprived”. Eight years later, in 1814, Twyford underwent further surgery for a strangulated hernia, but developed complications. He died on 22 November, aged 54.

A medical report by Dr George Freer, the same surgeon who had removed the lead ball, concluded that Twyford’s lung damage — suffered in the shooting almost a decade prior — was responsible for his death. Despite the Year and a Day Rule — a legal principle which stated that a death resulting from an attack could be classified as murder only if the victim died within a year and a day of the incident, Freer named Matsell as being responsible for Twyford’s death. From then on, history books declared Matsell a murderer until the story sank into relative obscurity.

Twyford and Matsell’s tale may have never resurfaced had it not been for the work of amateur historian Kay Hunter, from Aston, who prides herself on being an expert on all things hanging. In 1998, she was exiting The Actress and Bishop pub on Ludgate Hill and spotted something on its exterior: a plaque claiming the site was the location of the last public execution in Birmingham. Curious, she approached the Birmingham Civic Society who denied all responsibility, and Hunter deduced that the plaque had belonged to Ansell’s brewery, with their squirrel logo and the phrasing “this was for them indeed the last drop”.

She conducted some research. “I proved it was erroneous,” she says gleefully when we meet for coffee. This kickstarted the process of getting a new plaque installed at the correct location. Over the next 10 years, Hunter brought renewed public interest to the case. Partly thanks to her efforts, in 2018 Robert Twyford was commemorated on the West Midlands Police's roll of honour, displayed at the Lloyd House headquarters. Even now, more than 20 years after beginning her investigation, Hunter continues to write about and give talks on the subject. “I’ve been doing seven to eight talks a year to as many as 150 people,” she says. Evidently, Brummies remain fascinated by public executions.

Every day, thousands of people pass by the site of Twyford’s shooting. The now-dirty plate hangs, barely noticeable against the crumbling white brick and curtained by foliage. It mis-tells Matsell's legend: the tale of the murder that never was.

Did you enjoy this story? You can get two totally free issues of The Dispatch — including our Monday news briefings and the weekend read you're perusing right now — every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can contact us or visit our advertising page below for more information

Comments