In Jane Austen’s 1815 novel Emma, the character Mrs Elton is scathing about some recent acquaintances. “They came from Birmingham, which is not a place to promise much, you know, Mr Weston. One has no great hopes of Birmingham. I always say there is something direful in the sound.”

Her conversation felt like it was being repeated a few weeks ago, albeit on social media. It began with an article by Will Lloyd in The Times, which claimed Birmingham was “leading the nation in decline”. Typical of the reaction was one professional journalist, who pointed to English tourists going to Belfast and added: “can you imagine anyone having a city break in Birmingham?’ (In fact, according to VisitBritain, Birmingham is ahead of Leeds, Newcastle, Bath and Bristol in terms of visits for breaks, if you must know).

This might surprise some, and I’d argue that the reason for that surprise is also behind why Brum’s most struggling areas are taken as typical of the city in a way that they are not in other places. A ‘rough’ bit of Manchester or London is just that; an equivalent part of Birmingham is, well, just what you’d expect in that dump. Meanwhile, I was told just a few days ago that the ‘nice’ bits of Brum – Edgbaston and Harbone in this instance – were ‘not really Birmingham’.

The jump to these conclusions happens because Birmingham’s reputation has not been great for a very long time. Based on my own experiences, a lot of people, usually those who haven’t visited that much, think it’s ugly, boring, run-down and full of people with ridiculous accents. And that’s when they’re being polite.

Blame it on Brummie indifference or self-deprecation, but even the city's long list of achievements is little known. I’ve been asked on more than one occasion ‘what has Birmingham given the world except baltis, concrete and terrible cars?’ Well, maybe they have a point. Besides the first cotton mills, the first steam engines, the first plastics, the first building societies, two of Britain’s major banks, the first technical schools, the first red brick university, the first municipal art schools and concert halls, the football league, major early advances in nuclear physics, the first patient-controlled pacemaker, heavy metal, fantasy fiction and perhaps the entirety of industrial civilisation, what exactly has Birmingham done for us?

Part of the image is understandable. The city did make the worst town planning decisions in the country in the 1960s, with stiff competition. The best bits of Brum are spread out and hidden away; some other big cities have most of the stuff that’s worth visiting within a few minutes’ walk of the main station. We have New Street.

But the vitriol the city gets has always puzzled me. It’s understandable why it would be seen as lacking if your standard of city is York or Bath, Oxford or Cambridge. Even London. But why is it judged so poorly compared to the other inland industrial cities – Leeds, Manchester, Bradford, and Sheffield?

For me, it’s partly about geography, its straddling of both key transport links as well as the north/south divide that defines English life. But it's also about its history, and how its image has changed over time.

What’s more, as with Brum, all those cities have similar origins; small market towns, previously relatively obscure, that grew insanely fast in the late 18th and 19th centuries to become the largest cities outside London today. So when did things change?

Birmingham’s tendency to think of itself as being uniquely without history is odd, which I ascribe to it often comparing itself to the historic towns that surround it, rather than those obvious peers to the North. After all, Birmingham was larger earlier than the other industrial cities. By 1700, it was a town with as many as 20,000 inhabitants, compared to Manchester’s 15,000, Leeds’ 12,000, Sheffield’s 7,000 and Bradford’s 5,000.

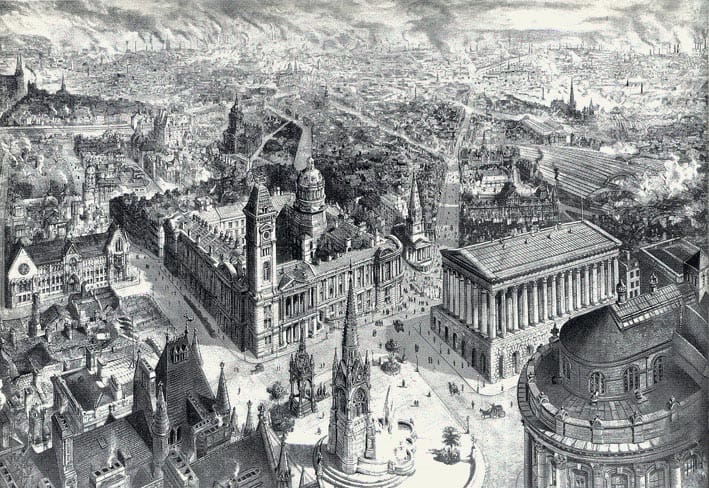

And its history as an industrial centre goes even deeper than those peers. By the 1500s it was already known for its metalworking; William Camden described it as a town “swarming with inhabitants and echoing with the noise of anvils”. A century later, Celia Fiennes noted that it was “very black and smoky, and all full of workshops, for they are a people that work very hard” – a sentiment that would be repeatedly expressed for the next few centuries.

Interestingly, though, while its later Victorian image is sometimes fairly indistinguishable from the other major industrial cities, early writers were often positive about the city – perhaps reflecting the positivity of Georgians towards industry, progress and cities generally. By the 1700s, its status as a centre of industrial innovation and intellectual life more generally was beginning to be recognised. Samuel Johnson called Birmingham “a city of philosophers” (meaning science), while the Scottish clergyman Alexander Carlyle described “a place where invention and industry go hand in hand, and where men seem to breathe nothing but trade and manufacture."

This reputation only grew over the century. Johnson’s biographer Boswell describes “everything in a state of bustling prosperity”; while the travel writer Arthur Young referred to it as “one of the most prosperous and busy places in the kingdom.” This was, of course, the heyday of the “Midlands Enlightenment”, with Birmingham propelled to the forefront of European science and invention.

While plenty of visitors continued to comment on its smokiness and dirtiness, they were sometimes also struck by its new face. While the old town around Digbeth and the Bull Ring was still an ash-encrusted chaos of forges, workshops and old buildings, there was also a new town: a classically planned Georgian one built by large landowners such as the Newhall Estate. This was focussed on the new church of St Philips’ (“a beacon of newfound elegance, rising above the manufactories in noble contrast”) and can still be felt in some of the streets nearby. William Hutton, the city’s first historian, describes the old town, “irregular and confused”, giving way to the new, “spacious and elegant, where every rising edifice seems to exceed the last in beauty”.

So far, so good. But this was all to change.

Sorry to interrupt your reading. But we're about to hit a paywall, which is how the Dispatch funds the dedicated local journalism we do. Don't panic though — right now, we're running an offer which means a Dispatch subscription is just £1 a week for your first three months. That's £4 a month for boots-on-the-ground local reporting you're just not getting anywhere else.

We'd love you to back what we do; in turn, you're getting a 50%. membership discount. Click the button below to find out more.