On a rainy June morning, a gaggle of Birmingham luminaries gathered under the masses of grey Brutalist concrete that makes up the intersection between Smallbrook Queensway and Bristol Street. The date was 1998, a year into New Labour’s bright-eyed new vision for Britain. It was a time when the country generally felt confident about its multicultural and postcolonial future. The previous summer, the former British colony of Hong Kong had been transferred back to China, marking improved relations between the two powers after decades of Cold War mistrust.

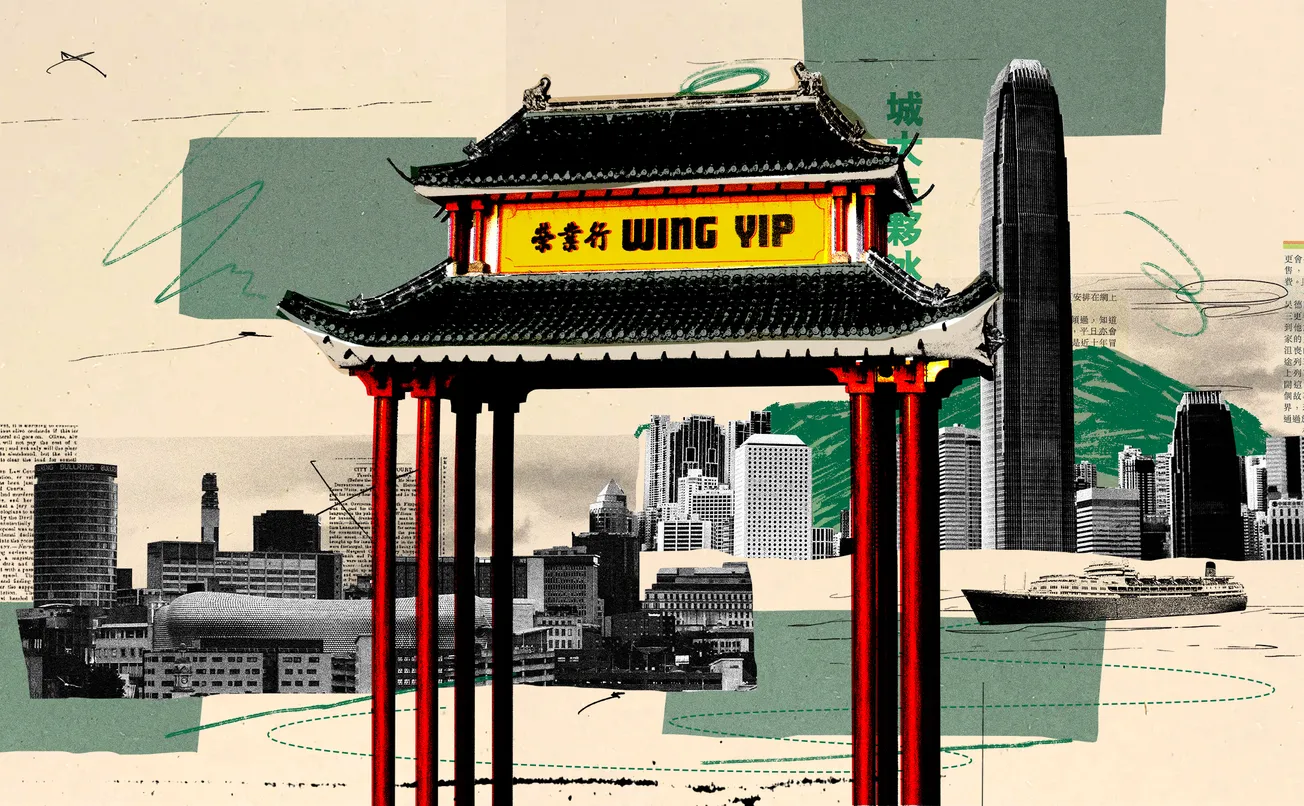

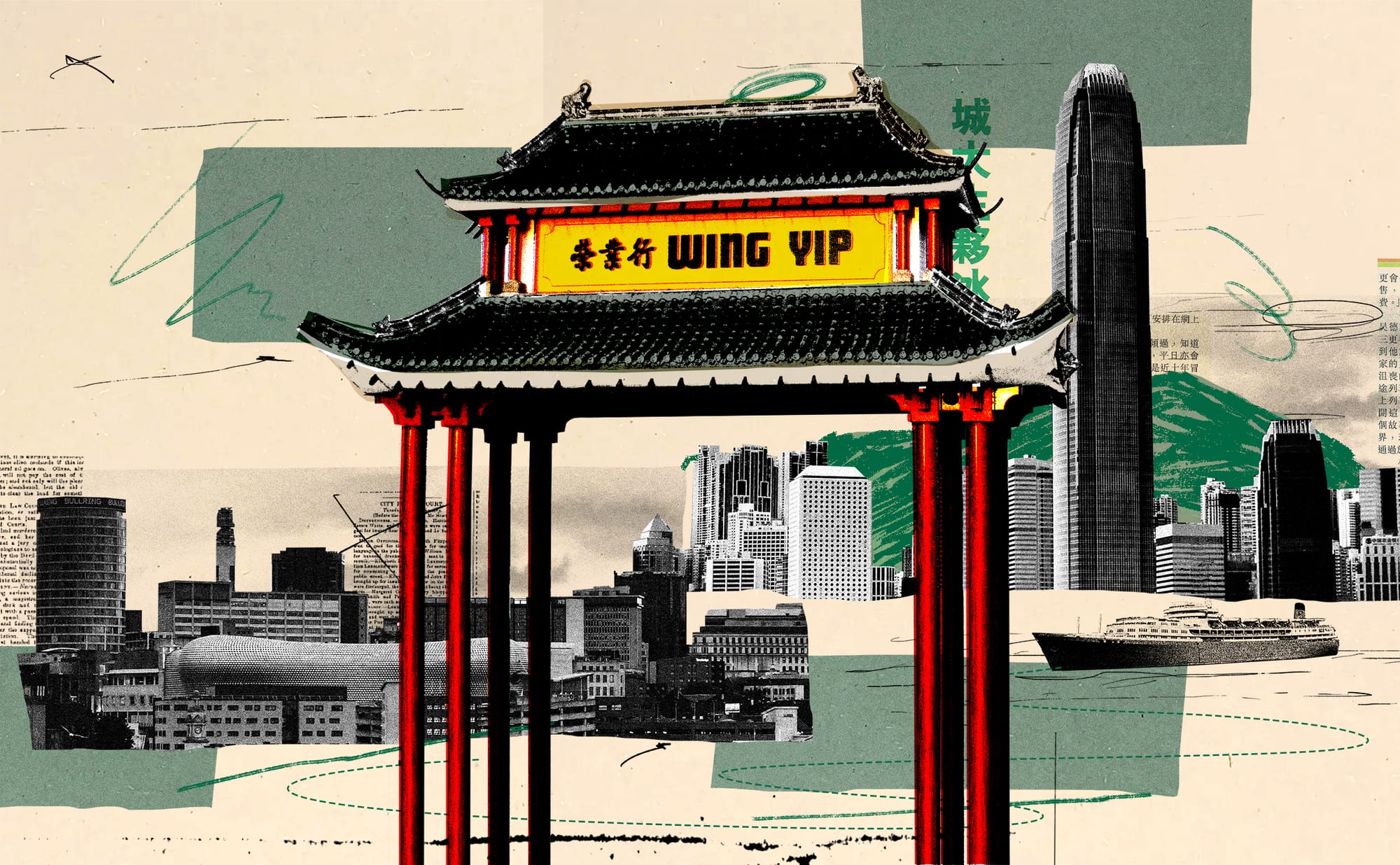

This thawing was also being felt at a local level. Birmingham’s great and good, including its Lord Mayor, had gathered that drizzly summer morning alongside a huddle of Chinese press to inaugurate a gift from one of the city’s most successful businessmen: Woon Wing Yip, a tycoon who earned his fortune via superstores selling Asian food wholesale to British takeaways. The gift was a 40ft, pagoda forged and sculpted in the marble quarries of Fujian, a south eastern Chinese province.

The pagoda’s dedication plaque “mark[ed] the establishment of improving Sino-Anglo relations in Birmingham.” The Lord Mayor gave a speech saying that the pagoda: “truly reflects and represents the Chinese community… now we can show our welcome to the Chinese.”

Four years earlier, Wing Yip told the Birmingham Evening Mail that he hoped his largesse — sporting a £90,000 price tag — would: “start a trend.” He wanted entrepreneurs from other ethnic communities to “follow his example by donating works of their own particular style of art to the city they have made their home.” Clearly, Wing Yip was the kind of businessman, concerned not just with profit margins and the accrual of assets, but civic vocation — giving back. It was the culmination of nearly two decades of positioning the company as one that returned more to its local community than it extracted.

Wing Yip is a Birmingham success story, a philanthropic family business in the vein of Cadbury’s, representing a new, global Britain. Nearly thirty years on, the company markets itself as the UK’s ‘leading Oriental grocer.’ But relations with the city have fractured. Wing Yip’s Nechells headquarters have ballooned into a huge campus and its expansion — including a gigantic cold storage unit — has angered locals. Meanwhile, intimate connections with British Chinese families have diminished with the closure of popular restaurants based at the superstore.

From teashop to mammoth cold storage unit

Step off the bus in Nechells and the first thing you'll see is a huge barracks of a building, decked out in green tiling and traditional Chinese ornamentation, rising out of Birmingham’s concrete 1960s suburbia. This is Wing Yip HQ. It's not the original site. That honour goes to Digbeth, where in May 1970, a young Hakka Chinese migrant from Guangdong set up a store named after himself.

Woon Wing Yip first arrived in Britain 1959. Depending on the source, he either had £2 (£40 today) or £10 (£201) in his pocket. But everyone agrees that he alighted in Hull and then made his way south, to the seaside town of Clacton, where he worked as a waiter. By 1962, the entrepreneurial youth had saved enough to set up a Chinese restaurant in a former tea shop. From there, he was joined by brother Sammy and they grew the company further, eventually opening three more restaurants and two takeaways in East Anglia.

Welcome to The Dispatch. We're Birmingham's new quality newspaper, delivered via email. Join our free mailing list to get two full editions a week: a Monday briefing, full of things to do and bitesize news, straight from Brum's streets, and a weekend feature, taking you deep inside your city and the West Midlands.

To get total access to all four of our weekly editions, you can join up as a paying member. We'd love that. But we understand you might want to try before you buy, so click below to sign up for totally free and start getting our special brand of local journalism straight to your inbox today.

In 1970, Wing Yip and his family moved to Digbeth and into the grocery business, where his shop became the “centre of the Chinese community,” says Paul Tilsley, former Lord Mayor of Birmingham, and deputy council leader. Tilsley worked alongside Wing Yip in the city’s wholesale markets in the early years. He remembers Wing Yip as a younger man: “[being] always very busy and always very astute.”

Wing Yip became the premier supplier of ingredients from East Asia, like preserved duck eggs and dehydrated fish, for the burgeoning Chinese restaurant scene in the city. Customers soon came from further afield; in his first year of business, Wing Yip told the Birmingham Daily Post that he sold to clients as far away as Derbyshire and North Wales. By 2017, Wing Yip was the UK’s biggest ‘Oriental’ wholesaler, supplying supermarkets like Tesco as well as their traditional base. By 2020, Woon Wing Yip — who snagged an OBE in 2010 — personally ranked 48th on the West Midlands rich list; last year turnover of the company he built was £90.3m with a pre-tax profit of £3.53m.

Since 1992, Wing Yip’s Birmingham home has been in Nechells. Since then, it’s grown into an entire complex of commerce, featuring a huge gatehouse, pagodas, Chinese guardian lions and housing an array of Chinese-run community businesses such as a lawyer, travel agent and massage parlour.

The glitz stands out in Nechells; the ward is one of the poorest in Birmingham. According to 2021 census data, 45.1% of the working age population has never been employed — 27% have no formal qualifications. Child poverty rates are over 50%. Austerity has hit community assets hard; Nechells lost its 19th century library in 2013 and its community centre in 2024. But while Wing Yip and his heirs have made a name for themselves in corporate philanthropy — a great Birmingham tradition — Nechells locals say they see little benefit. “They don’t care about the community at all,” says Danielle, a long-term resident.

Resentment has heightened in recent weeks, over a new cold storage warehouse being constructed by the superstore. At 21 meters high, 87 meters long, with a width of 35 meters, the building — which abuts several Nechells houses — has caused a furore. Residents complain that they haven’t been properly consulted, that the council hasn't listened to their objections, and that the unit will block out sunlight and cause noise pollution.

Danielle claims Wing Yip have used nefarious means to get the planning permission for the structure — they own a lot of local properties, buying up the vacant shells of shuttered stores. She shows me a planning document of nearby properties surveyed about the cold storage plans. A large minority of the properties on the sheet are Wing Yip owned addresses. They own “20 out of the 50 properties surveyed” she tells me. Danielle also informs me that a road leading to a local primary school is also being closed to make room for the warehouse. After the site is finished, residents expect that large lorries will be coming down the street next to the school.

For its part, Wing Yip told The Dispatch that their two-week public consultation on plans, conducted in March 2022, was comprehensive. In a statement, the company said: “the consultation was supported by both a project website and leaflets delivered to around 100 neighbouring properties” and that Birmingham City Council carried out a subsequent statutory consultation in May of that year.

As a direct result of the process, “the proposed height of the new building was reduced by 20%, while other resident concerns regarding noise and highways access were also addressed.” The public, added the statement, “were able to respond to the plans all the way up to its determination by Birmingham City Council’s planning committee in December 2022.”

“[Wing Yip] do sod all for the community” says Nechells homeowner, Mohammed. I meet him outside his property, where he’s chatting to neighbour Raj. Behind their chimneys, the vast Wing Yip complex looms. Raj takes me into his upstairs backroom, pointing out the frame of the huge new warehouse that towers over his garden and children's trampoline. “Now, do you reckon that’s 21 metres?” he asks me. Danielle tells me there is a nearby commercial unit owned by Wing Yip at 10 Nechells Park Road, currently being used as a staff car park, that could be adapted for cold storage instead. I ask her why they don’t build there. “Behind our houses is cheaper,” she replies.

“We don’t benefit at all from having Wing Yip here,” says Rakia, a mum I bump into on the school run, as I’m leaving Raj’s. “I don’t know anyone from Nechells employed by them.”

Charity, but for whom?

Woon Wing Yip prides himself on the philanthropic side of the empire he’s built. In a revealing, rare 2003 interview, he sat down with Wun Fung Chan, an academic from the University of Strathclyde. Chan was writing an essay about Wing Yip’s donation of the pagoda to Birmingham. Unlike more conservative profiles of Wing Yip, produced by outlets like the Financial Times, Chan’s essay offers a glimpse of the entrepreneur at his most unfiltered.

“We are self-reliant,” Wing Yip tells Chan, referring to himself and the wider Chinese community. “We always leave some change behind. We Chinese contribute to society, taking out, we always the bottom line still in black. There are a lot of communities and a lot of races that probably take more than they contribute. Am I right?”

Wing Yip the business does give back to Birmingham — just perhaps not in its own backyard. In 1986, the W Wing Yip and Brothers Trust — which became the W Wing Yip and Brothers Foundation in 2022 — was established, with a focus on funding education and medical initiatives. In 2000, the organisation began providing bursaries to students of Chinese heritage experiencing financial difficulties. By 2008, the foundation had reportedly already given out over 300 educational awards, although, according to Wing Yip’s website, the scheme seems to have closed at the time of writing.

The foundation is still handing out “local community grants.” However, the charity’s accounts show a 48% reduction in contributions last year, from £97,500 down to £50,000. The biggest block of money in 2024 went to educational causes — reportedly Woon Wing Yip “sees [education] as the secret of his own success” — with £28,000 in donations split between the Overseas Chinese Association School, Birmingham Chinese School and Loughborough University.

A further £9,000 was spent on ‘community welfare’, including £2,800 to Birmingham Chinese Festival and £700 to St Matthew's Community Hall in Walsall. Thirteen thousand went to various medical causes.

Notably, there are no donations in either 2024 or 2023 received by local Nechells groups or organisations such as Free at Last, or the Nechells POD which aim to address poverty and community cohesion in the increasingly deprived neighbourhood.

Losing community roots?

It’s not just Nechells locals who feel a loss of connection with Wing Yip. The superstore’s status as a touchstone for the Chinese diaspora is changing too.

“We’d always made a trip to Birmingham for a big shop and make a day out of it,” says Lisa Wong. Her parents ran a Chinese takeaway in Coventry. “They used to have [dim sum restaurant] Wing Wah on the premises, where we’d have lunch before shopping. It was an event.”

In the 1990s, Wing Yip “had more food, more options,” she remembers. Now, Wing Wah is gone and “it feels hollow — Birmingham and Coventry have so many Chinese mini-marts now, and bustling Chinese quarters, fewer people are going to Wing Yip.”

Angela Hui, the author of Takeaway, a memoir about British-Chinese takeaways, grew up in Wales. She and her family used to drive from their home in rural south Wales to Birmingham, just to visit Wing Yip. “[It’s] mad looking back,” she marvels. “At that time in the 1990s, there was nothing. Birmingham was the nearest Chinatown.”

But times have changed. Along with other East Asian food and retail businesses, Chinese restaurants and grocers have exploded in popularity. Hui hasn’t been to Wing Yip for a long time — “since I was a kid” —, but she says the superstores have taken on a more sentimental role than a practical one. “It’s a pilgrimage going there.”

Woon Wing Yip is now in his late eighties; the company is managed by sons Brian and Albert. It seems to be at a crossroads; many people I talked to describe the superstore as ‘legendary.’ But the active role it played for British Asians — both individuals and businesses — in the 1990s and 2000s has faded somewhat and profits reflect that, declining by over £5m between 2023 and 2024.

The Chinese community’s emotional ties to Wing Yip are fraying and wider affection won from Birmingham’s general public for its corporate philanthropy is on the wane. Such a reputation was hard-won under Woon’s tenure. Whether it’s able to be maintained it is an open question.

Have you been to Wing Yip recently? Have memories of it in days gone by? Thoughts about where it fits in Birmingham today? Let us know in the comments.

Comments