“I’d love to get George Galloway up on the roof,” jokes Bob. “I’d like to get him up there next to the Palestine flag, get him to smash a bottle of champagne with a sword.” I’m in Moseley talking to the owner of Cafephilia, a beloved local cafe, which sports the biggest Palestinian flag I’ve ever seen on its roof. When I tell Bob that Galloway’s newish political vehicle, the Workers Party, is headquartered five minutes down the road at the Moseley All Services Club, he jumps up in excitement: “I had no idea. I don’t know what the Workers Party is, but I like Galloway, get him to come here!”

He’s not alone in lack of acquaintance with the Workers Party. From canvassing Moseley’s residents, few seem aware that their ward is now home to a party that’s positioning itself as the left-wing version of Reform, and has become somewhat of a boogeyman to the two most dominant political factions in the UK. But as with Reform, there’s a story to be uncovered in why this new populist party has chosen to laser in on the country’s second city. What fertile ground does the Workers Party perceive there to be in Birmingham? And how are they going about pollinating it?

The inner sanctum

I’m sat among an audience of three in the Workers Party headquarters, which are based on leafy, middle-class Church Road. This is the grand total of attendees for the party’s Birmingham branch meeting today — although, those present tell me that national meetings in Moseley are often in the high twenties. It’s not exactly the numbers I expected from a party trumpeting itself as the next radical, populist challenger to the status quo — however, it is a Sunday.

Formed after an emphatic defeat in 2019 for a Labour party pledging a social democratic national agenda, the Workers Party is economically left and socially conservative, echoing the success of similar movements across the globe such as Morena in Mexico, the Danish Social Democrats and the BSW (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht) in Germany. These parties, which mix populism, socialism and cultural conservatism, have all made gains in post-industrial heartlands and deprived areas similar to Birmingham such as East Germany and southern Mexico.

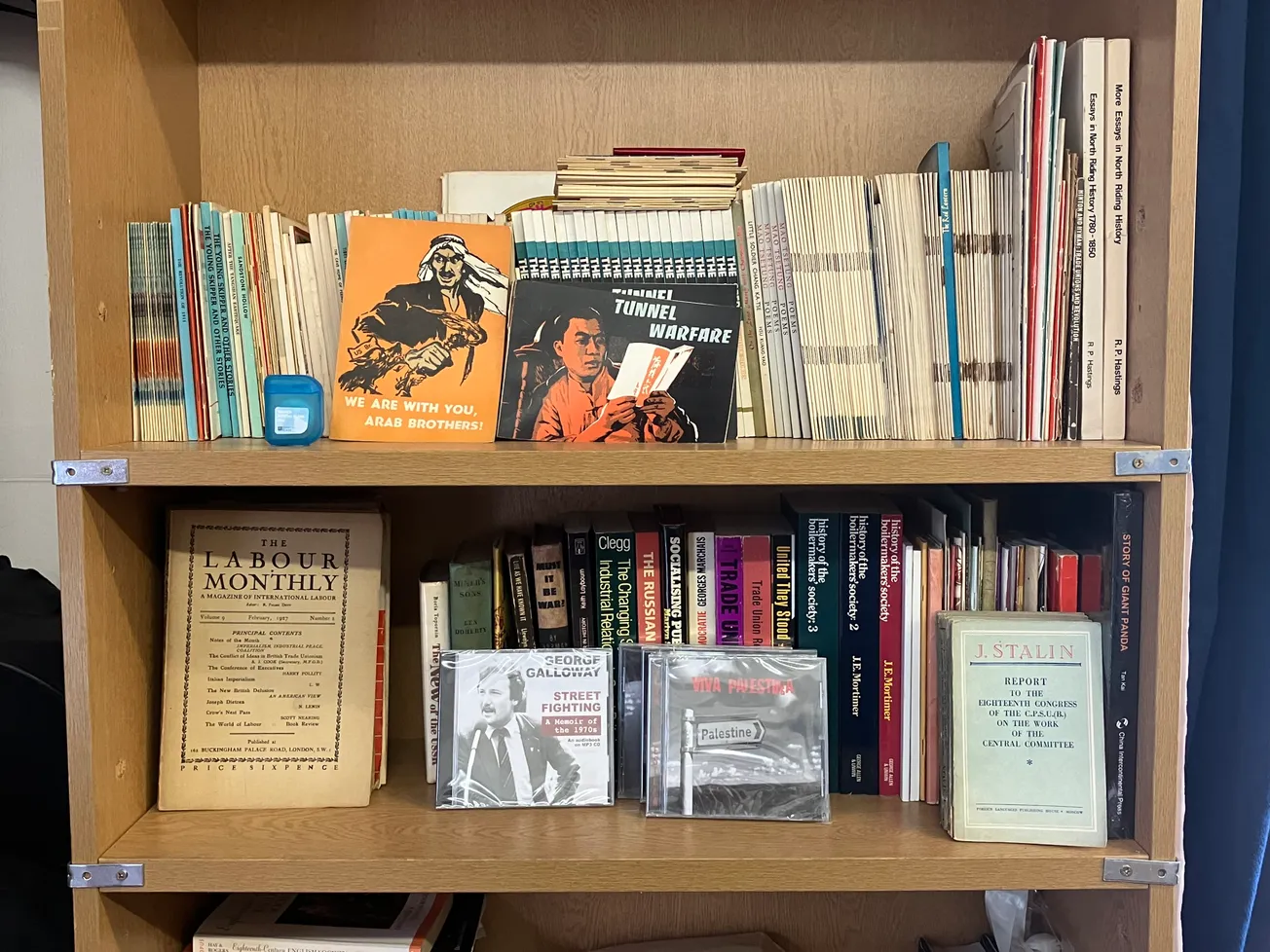

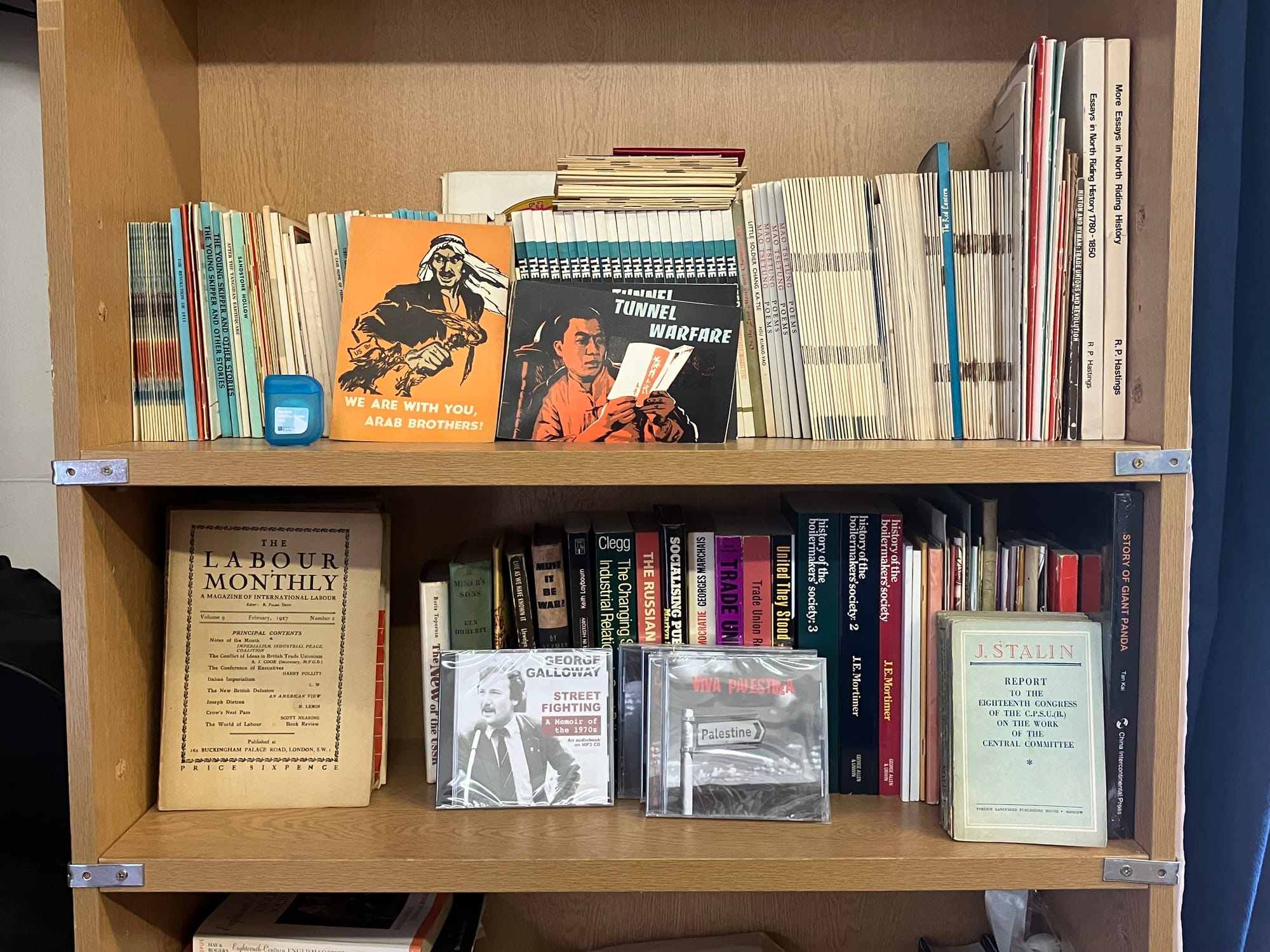

The interiors of the Workers Party HQ, communicate their position: both salt of the earth and airily intellectual. The first set of rooms features thick carpets, low ceilings and dark wallpaper — a classic working man’s club. Upstairs, their meeting room is defined by clashing iconography, reflecting their jumbled politics; paintings of WWII bomber planes, next to bookshelves stacked with revolutionary texts by Lenin and Michael Collins. In the corner I spot a photo of King Charles. “That’s just there to annoy people,” Peter Higgins, the contact I’m meeting, tells me. “We like to confuse.”

Higgins, who now serves as a member of the executive committee of the Workers Party and head of its administration, grew up in Protestant East Belfast, deeply enmeshed in trade unionism and the Progressive Unionist Party, which described itself as being both Democratic Socialist and Loyalist in orientation. He left Northern Ireland for university and eventually found himself in China, working as an independent translator for the communist government. Higgins describes the Moseley headquarters of the Workers Party as “the rhythm section” of the movement to me.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free issues of The Dispatch — including our Monday news briefings and the weekend read you're perusing right now — every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

The reason the Workers Party has its headquarters in Moseley is simple, says Higgins; senior members, like party general secretary Paul Cannon and Higgins, live here, alongside a smattering of activists and branch members. Higgins tells me he ended up moving to Birmingham and joining the party because he realised: “there’s no space for me politically [in China], the pull factor brought me back in 2019”.

Birmingham, he says, is of vital importance to the Workers Party.

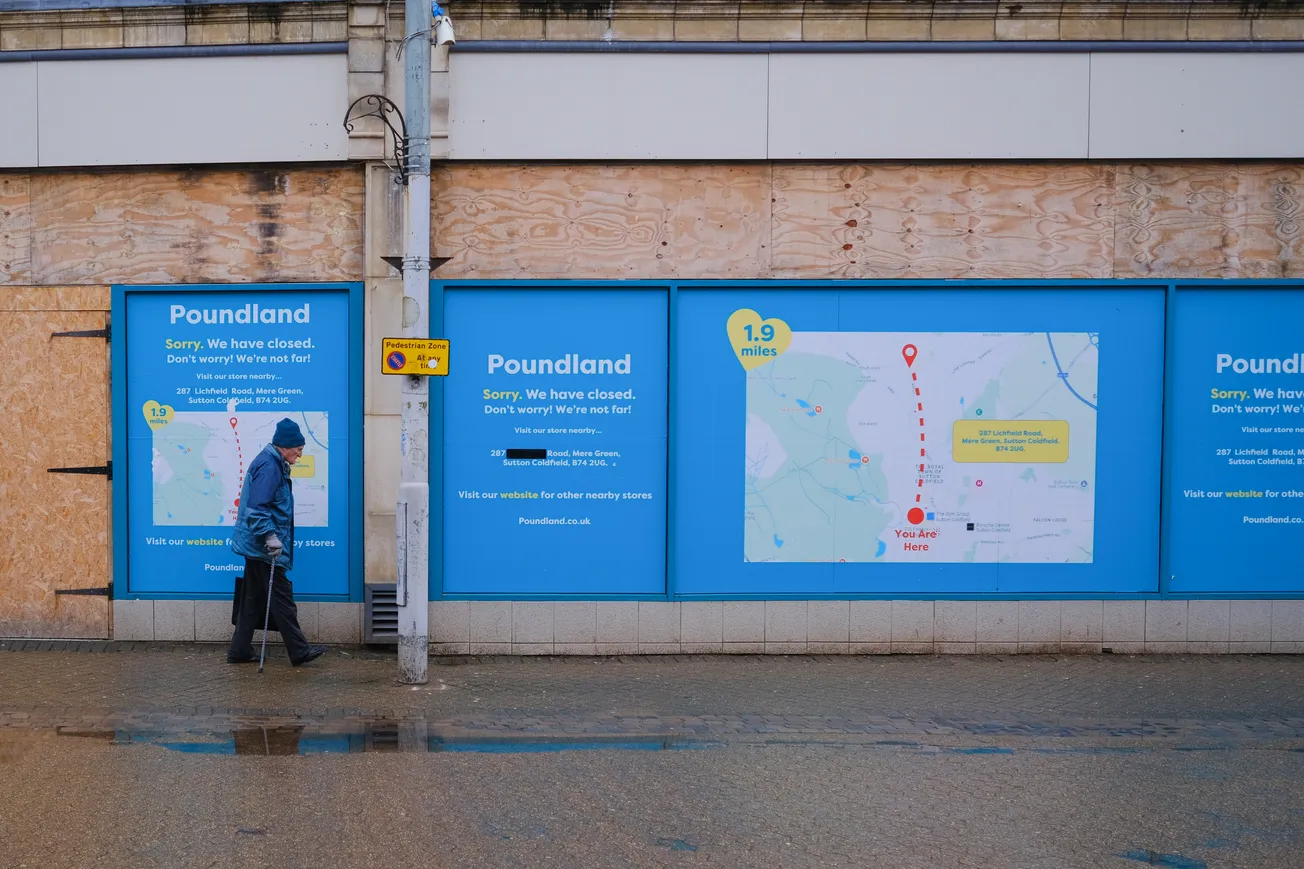

“The issues that we face in Birmingham, as a former centre of industry, the death of industry in this area of Britain in the West Midlands and the Black Country — this was a civil war fought against the working class. Now our working class has been outsourced to Bangladesh, India. The UK is reaping the consequences of that in terms of an ageing population, an economy that has to be run on immigration. This all began with a political war against the working class.” Indeed, the party is particularly focused on recruiting Birmingham’s multi-ethnic working class population to their cause.

The Birmingham connection?

Outside of the Workers Party HQ, members of Moseley’s working class don’t seem too aware of the movement in their midst attempting to fight such a conflict on their behalf. I chat to a young South Asian bloke behind the counter at Boo, a local smash burger joint. “I ain’t heard of them, no” he tells me. “But maybe they can sort out the alley behind the Prince of Wales [pub] people keep drinking and smashing glass there.”

Birmingham deserves great journalism. You can help make it happen.

You're halfway there, the rest of the story is behind this paywall. Join the Dispatch for full access to local news that matters, just £8/month.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign In