🎁 It's not too late to give something thoughtful, local and completely sustainable this Christmas! Buy a heavily discounted gift subscription and every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to Birmingham — a gift that keeps on giving all year round.

You can get 38% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

In The Pickwick Papers, — Charles Dickens’ first literary success — Mr Pickwick travels into Birmingham from London, via the Bristol Road and Five Ways. Here he is confronted with “the sights and sounds of earnest occupation…[the] streets were thronged with working people…the clash of hammers and rushing of steam.”

It’s a vivid portrait of the 19th century town’s chaotic thrum, the energy that drew the author back time and time again. Because Dickens was obsessed with this dirty, industrious place. To use modern parlance: he was positively Birmingham-pilled. Which is why it isn’t surprising that, 172 years ago this week, he chose this place as the location to perform his first ever readings of perhaps his most well-known work: A Christmas Carol.

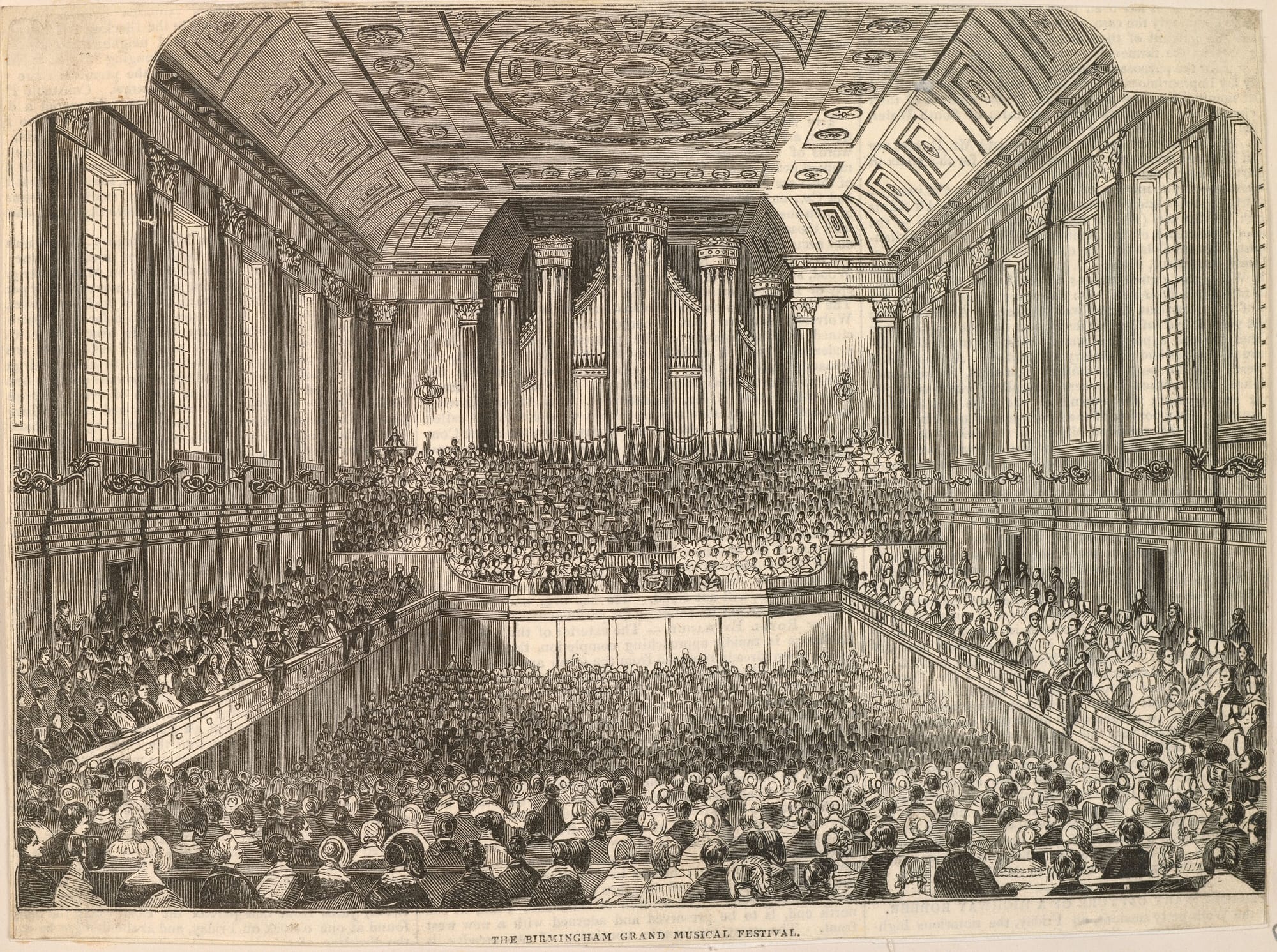

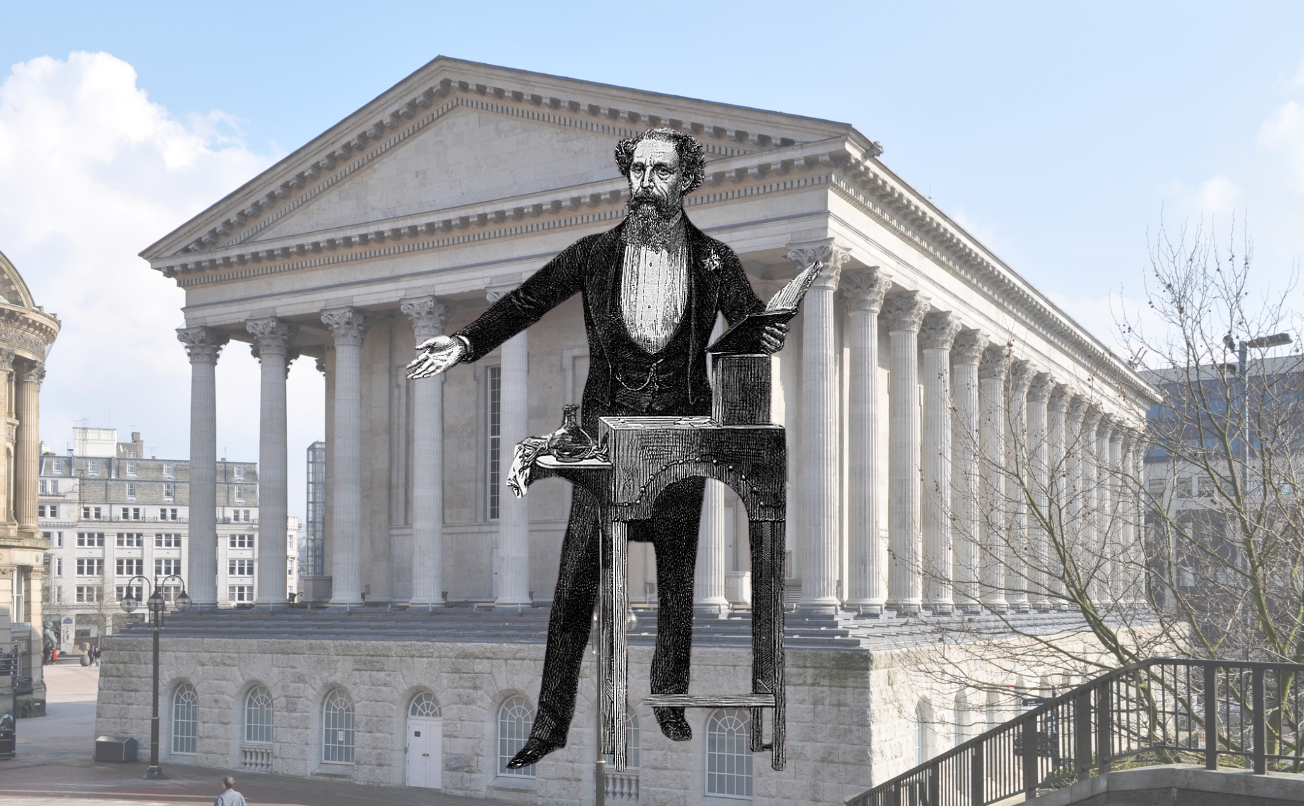

While everyone from the Muppets to the cast of EastEnders has since adapted the story, the original telling of miserly Scrooge and his timely visit by three, festive ghosts took place right here, on 27, 28 and 30 December 1853. Dickens performed the readings on the stage of Birmingham’s Town Hall — which was thrice packed out, naturally.

This wasn’t accidental. The author was “a great friend” of Birmingham, says local historian and Dickens expert Professor Carl Chinn. The A Christmas Carol readings were planned to raise funds for an accessible education centre — the Birmingham & Midland Institute — of which Dickens would go on to be president in 1869. He was taken with the then-town’s lively industry, political radicalism and the determination of its working classes. “[A] town of dirt, ironworks, radicals and hardware,” he wrote after his first visit in November 1834, when he pitched up here as a political reporter for London’s Morning Chronicle.

This arrival would be the beginning of a decades-long mutually beneficial relationship. As well as The Pickwick Papers, Dickens’s experiences in Birmingham would go on to inform The Old Curiosity Shop, in which the protagonists escape from London to Birmingham, along its famous canals. Elsewhere, Dickens called Brum “that great ingenious town” and said it could count on him as a friend. The city could do with such a friend now, as outsiders jostle to malign it.

Take Conservative MP Robert Jenrick: earlier this year, he declared Handsworth a slum with no white faces, a claim disproven by The Dispatch. The Telegraph has also pitched up in Erdington, claiming it has no community: again, The Dispatch found something different. And a phalanx of small-time YouTube content creators have long swarmed the Soho Rd, mostly taking aim at those in poverty.

Birmingham has undeniable problems: drastic council funding cuts and the long-running bins dispute to name a couple. There’s also a worklessness crisis, and today’s regional economy is sluggish. But if Dickens were alive today, it’s hard to imagine he would take the same, cynical view as Jenrick and co.

Admittedly, contemporary Birmingham is not the town Dickens once visited, which was “at the forefront of the democratic movement,” explains Chinn. 1830s Birmingham was growing, abuzz with industry and boisterous political ambition. Halesowen-born banker Thomas Atwood garnered cross-class support via his Birmingham Political Union for the 1832 Great Reform Act, giving the town political representation and its middle classes the vote. Later on, Birmingham would be central to the working-class Chartist movement.

Such energy captured Dickens: his first article about Birmingham was a dispatch from a Liberal meeting at the Town Hall. Birmingham, says Chinn, in particular its working classes and industry, “engrossed him”. “He’d go into pubs in poorer areas to get ideas for his characters,” he says. Dickens spent time in Digbeth, Deritend and “The Gullet”, a down-and-out-street in the centre of town, roughly near where the Birmingham law courts are today. Here lived some of the city’s most destitute people — there’s a rumour that Dickens himself dressed up as a poor man to fit in.

“He had empathy with the poor,” says Chinn. And the poor loved his work. It was serialised, for one thing, which meant groups could chip in to buy a copy and read it together, or listen as one person read aloud. In fact, Brummies loved it so much that they fundraised to pay for a small silver salver and a diamond ring, which they presented to Dickens at the Society of Artists in New Street on 6 January 1853, as a sign of their appreciation. He supposedly wore it for the rest of his life as a symbol of his affection for the town.

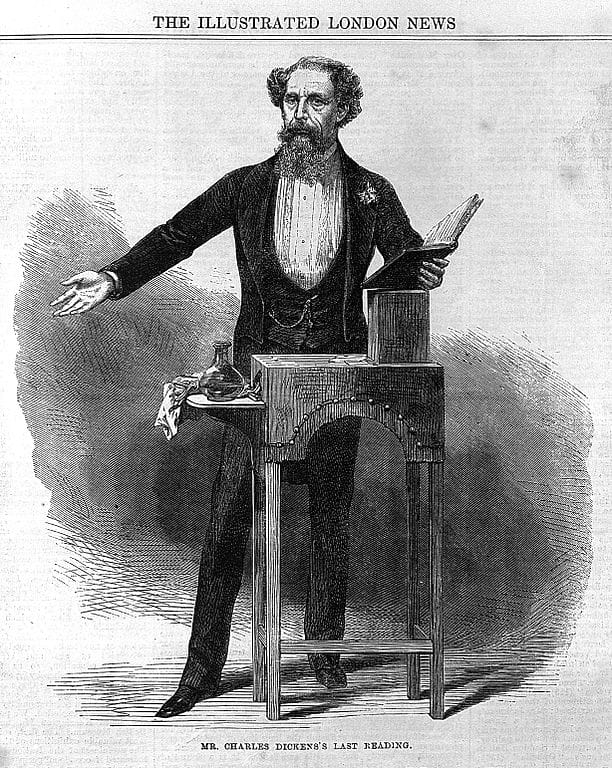

Touched, Dickens gave a present in return: he agreed to help raise funds for the Birmingham & Midland Institute (an accessible education centre) by reading A Christmas Carol, only if the working classes could afford to attend. He got his wish — the poorest were let in on the final night for just 6p. Dickens didn’t scrimp himself, however. Taking to the Town Hall stage, he wore his finest evening wear to showcase for the first time Ebeneezer Scrooge and the ghosts of Christmas past, present, and future. He read for more than three hours.

“Such were his mimetic abilities,” says Chinn, “that [on the last night] the working classes almost rent the roof as they cheered” — ie, they nearly took it off. Years later, when Dickens died in June 1870, the Birmingham Gazette wrote that the town had “special reason to mourn him”.

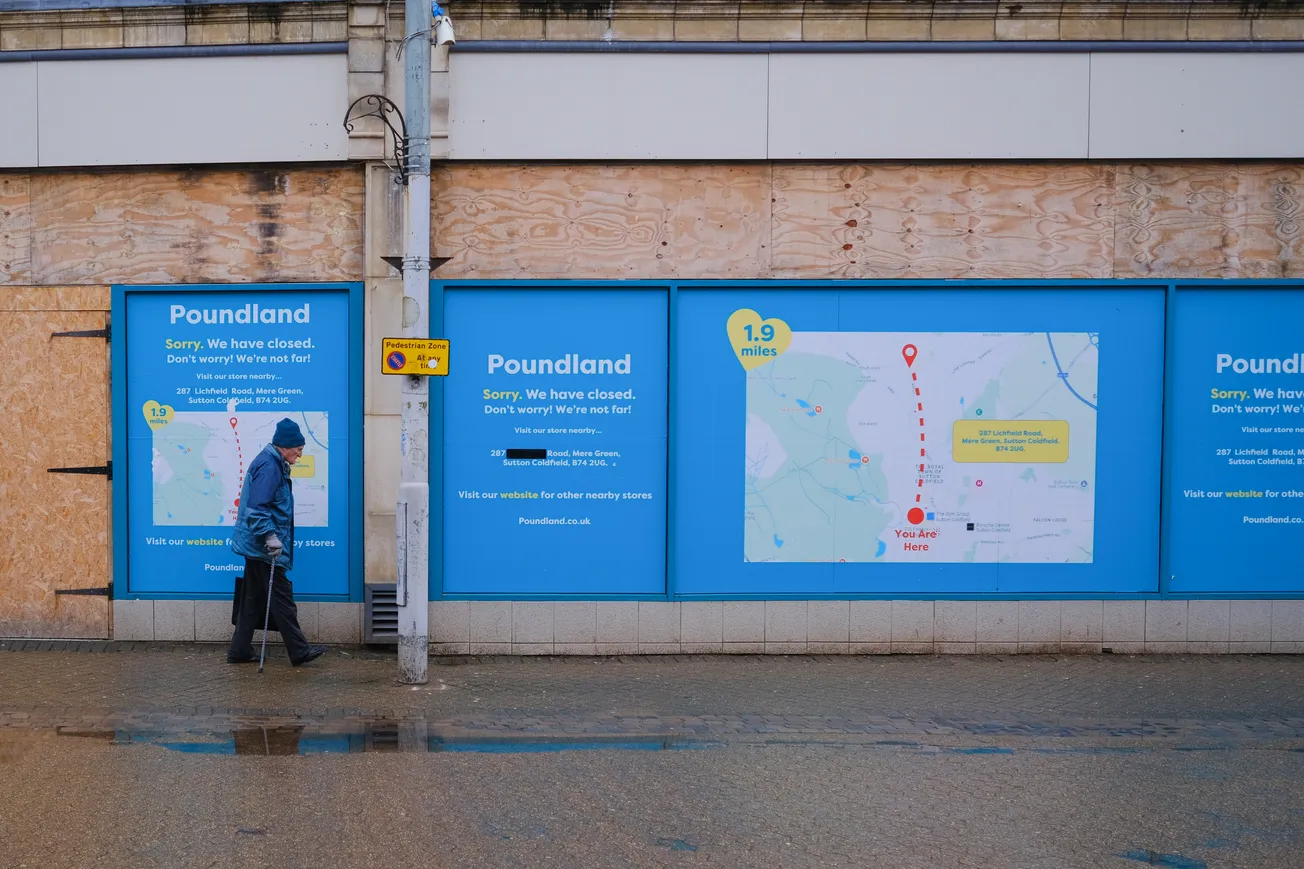

While deprivation in Birmingham might not be at Dickensian levels today — “in the Dickens era it was a dire, absolute poverty,” Chinn tells me — they are on the rise. No less than 46% of the city’s children are living in poverty, up from 27% in 2015. That’s twice the national average. It is these conditions that many people from outside the city turn up to ogle at and broadcast, clamouring to get the most extreme content for clicks. Why?

Chinn thinks it’s because “we do not fit into their version of England… Birmingham is a diverse city.” He believes there’s a narrative gap that’s being exploited to critique migration and promote nationalism. He thinks we haven’t been successful or loud enough at celebrating who we are as a city. “Our council acts in an isolationist way… it won’t champion things outside of their version of Birmingham,” he adds.

In Chinn’s view, our leaders need to boost Birmingham so there isn’t space for such negative stories to take hold. “When outsiders come to places like Soho Road, there are so many positive things they could say,” says Chinn. For one, “It’s got the most independent shops in the country.” Birmingham might not have the vigorous economy of the 1830s, but there is still world-class manufacturing: the storied precision stampers Brandauer, and JLR suppliers Sertec, too.

Then there’s the culture: heavy metal and bhangra emerged here, of course, but Birmingham also saw the rise of tennis and the football league. As for literature, who could forget Tolkien? But you might not know, as Chinn tells me, that “Washington Irving, the godfather of American Literature, even started writing Sleepy Hollow and Rip Van Winkle here.”

It isn’t all forgotten. Earlier this month, Birmingham Civic Society unveiled a blue plaque at the Town Hall to commemorate Dickens’ performances of A Christmas Carol. It was partly funded by B:Music (the charity which runs Symphony Hall and Town Hall) itself a recipient of council funding. But this kind of resource doesn’t exist for all venues in Brum. To add to the pressure, council funding for the arts will be entirely withdrawn next year. The Crown, where Black Sabbath first gigged, was at one time also earmarked for council funding to be put back into use. That didn’t come to be.

But hoping for another figure like Dickens to fight on behalf of the city, its citizens and its culture would be a fool's errand, says Chinn. “The context and time and place changes, even Dickens himself wouldn’t be the same [were he around now]”.

Chinn would know; at his pre-Christmas lecture, at Nortons pub in Digbeth, he gave a reading from A Christmas Carol, complete with theatrical “Bah! Humbug!”s that amateur thespian Dickens would surely have loved. But there was as much talk of the fight by lesser-known Brummies to save libraries and other public buildings, as there was about the past.

“What Dickens liked is the way people in Birmingham got on with things,” says Chinn. Perhaps today, the city will need to be saved by Brummies ourselves — not a single benefactor or friends in high places. And certainly not rogue vloggers.

24/12 correction: Dickens first visited Birmingham is 1834, not 1832 as originally stated. This has been corrected.

🎁 It's not too late to give something thoughtful, local and completely sustainable this Christmas! Buy a heavily discounted gift subscription and every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to Birmingham — a gift that keeps on giving all year round.

You can get 38% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

Comments