It's one of the first sunny days of the year. Birmingham is in the news: the bin strike has just started and images of terraced streets filled with litter and bin bags are everywhere.

This all feels very far away, though, as I get off the 24 bus in Harborne. It looks just the same as usual – clean (ish), traffic-choked, a little bit underwhelming architecturally, given its reputation and the leafiness of the side streets. I know, of course, that the village proper is hidden away to the south of here, but I’m not headed there today. Although I’ve never lived on this side of town, I know Harborne well.

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

My Nan, who had spent most of her life up the road in Bartley Green, loved visiting to go shopping or have a coffee; she ended up moving here, to a council retirement flat, just before she died. At school, we’d had to trudge around these streets mapping out the age and architecture of buildings – something that, in hindsight, may have been career-formative.

Just off to the right, though, I’m reminded why this part of town is so popular – trees and greenery surround generous Victorian terraced houses, with a few stucco-clad survivors from even earlier. I detour a little to pass through Moor Pool (or the ‘Harborne Tenants’ Garden Suburb’), the remarkable area planned and developed by the housing reformer John Nettlefold, Joseph Chamberlain’s nephew, as a template for how Birmingham would develop outwards along new transport arteries.

It’s so Hobbit-like, I wonder if it’s been missed out of the long list of places in Birmingham that inspired Tolkien, who grew up not far from here. I then remember that, remarkably, it was built after his time in the city (and that he hated suburbs). Despite Tolkien's distaste for them, Birmingham, at least to the south, has much more pleasant inner suburbs than most other industrial cities. As the architectural critic Jonathan Meades writes, the city’s “southern suburbs are lavishly green…. picture-book anthologies of all the domestic architectural styles of its long innings as the manufactory of the world.”

But I’m not here to pontificate on the local architecture. I’m about to embark on an entirely new experience for me – one of the most unusual that Birmingham has to offer. A journey, if you will, through space and time. Yes, I’m about to trek the Harborne Walkway, the empty bed of what was once the city’s first dedicated commuter line. Now a green corridor, I think the path explains everything about why this part of the city is how it is.

The roughly two-mile Harborne Walkway route takes you from the leafy suburb into the city centre. Within minutes of beginning, it feels like I am in a different world where the sound of birdsong is louder than the traffic. Reaching the far end of the walkway, in Summerfield Park on the Edgbaston/Ladywood fringes, feels just as bucolic, despite it being a stone’s throw from the city centre.

Walking back, the city begins again; I enter sterile streets south of Edgbaston, all massive piles and SUVs behind electric gates — so different from the Calthorpe Estate thoroughfares, closest to Five Ways, with their lovely, urbane Regency and early Victorian streetscapes.

Continuing on, I’m suddenly back in the bustle of Harborne again. It’s a strange contrast with the eerie silence of Norfolk Road. Why does that happen? Why can I go further out from the centre and yet it becomes busier and denser – from detached houses to terraces?

The answer to that question lies really in the nature of the Calthorpe Estate, but also in the railway bed I’ve just walked.

A new network

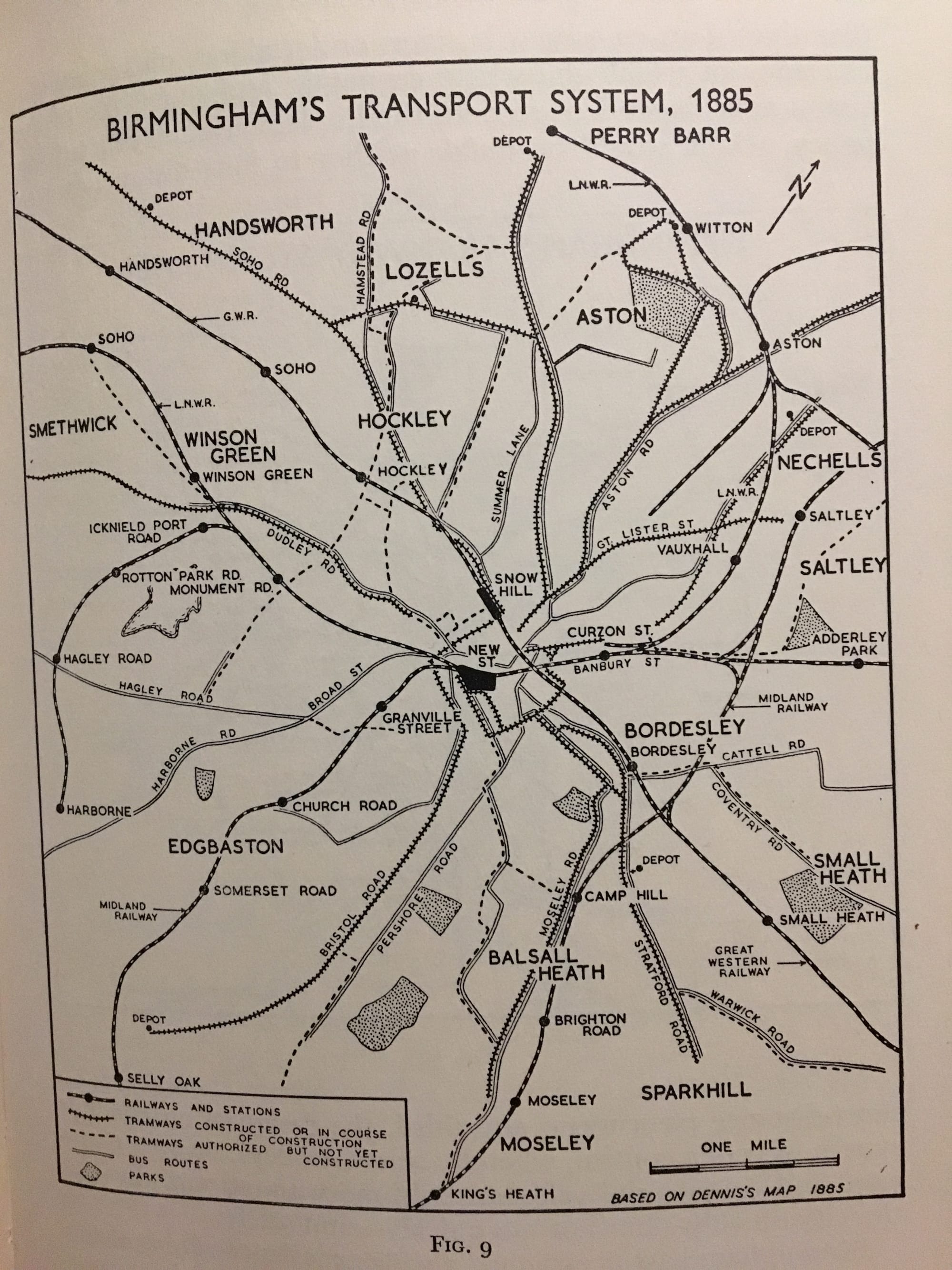

By the late Victorian era, railway routes like the one developed in Harborne were already peppering London – Birmingham, too, had some inter-city lines – but this was the first explicitly designed for commuting.

It was authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1866 and opened in 1874; a single track line running initially from New Street to Harborne via stations at Monument Lane, Rotton Park Road and Hagley Road.

Harborne had once been a rural Staffordshire village, where some of Birmingham’s elite owned country homes — famously the city’s first MP, and champion of reform, Thomas Attwood. It had remained so even as the rest of the city developed, thanks to it being separated from the core by the Calthorpe Estate.

But the railway opened Harborne up for a new form of development. Terraces of all types, and some grander homes, sprang up around the station. The area may now be seen as quite bourgeois, but originally the line and the more modest houses were popular with a type of worker that was springing up in Birmingham during the second half of the 20th century: the lower-middle class clerical worker, based in offices not in factories. They could not only use it for commuting, they apparently also used it to head home for lunch. There were, of course, richer types attracted by easy access to the larger “villas”.

Development was triggered all around the line; the houses on the north-western side of Edgbaston, on the Ladywood fringe, date from a similar era, and catered to similar classes. But development followed the railway, which had had to follow a fairly circuitous route, avoiding the land owned by the Calthorpes. The family wanted to preserve the value of their estate by maintaining it as a collection of country homes for the city’s elite, untainted by industry – or indeed shops, pubs or restaurants. This was perhaps a reflection of the abstinent tastes of that elite, who were unitarian or quaker by religion.

The most exclusive core of the estate, was to use the phrase of the time, ‘protected’ from the more ordinary suburbs cropping up around it by more lower-middle-class roads – the ones that, today, seem the most characterful.

A slightly later commuter line, The Birmingham West Suburban railway, built between 1876 and 1885, got around the Calthorpes’ restrictions by following the canal through an existing cutting. Leaving New Street, it ran through lost stations at Church Road and Somerset Road before Selly Oak and what was then called Stirchley Street (renamed Bournville after the Cadbury factory opened nearby).

This is now part of the Cross City Line (and indeed Cross Country, with trains travelling to Bristol and beyond), but in its origins it was also a commuter-only line — and Selly Oak and Stirchley are also railway suburbs of the same era as Harborne, albeit perhaps more “artisan” (upper working class in today’s terms) than clerk. Other examples — on a line that is soon to be brought back into use — include Moseley and King’s Heath.

This was the era of the “by-law terrace”. For many – not all – workers' wages were increasing, and the government had introduced new rules to banish the back-to-backs, provide better sanitation and minimum dimensions for rooms and the space around houses.

The result was these new terraced suburbs. They had to be within walking distance of the station so are fairly densely packed in, a feature that gives them vibrancy today. They stand in contrast to parts of the inner city where the back-to-backs and terraces were swept away with slum clearance and replaced with something rather more spread out, catering to the motor age.

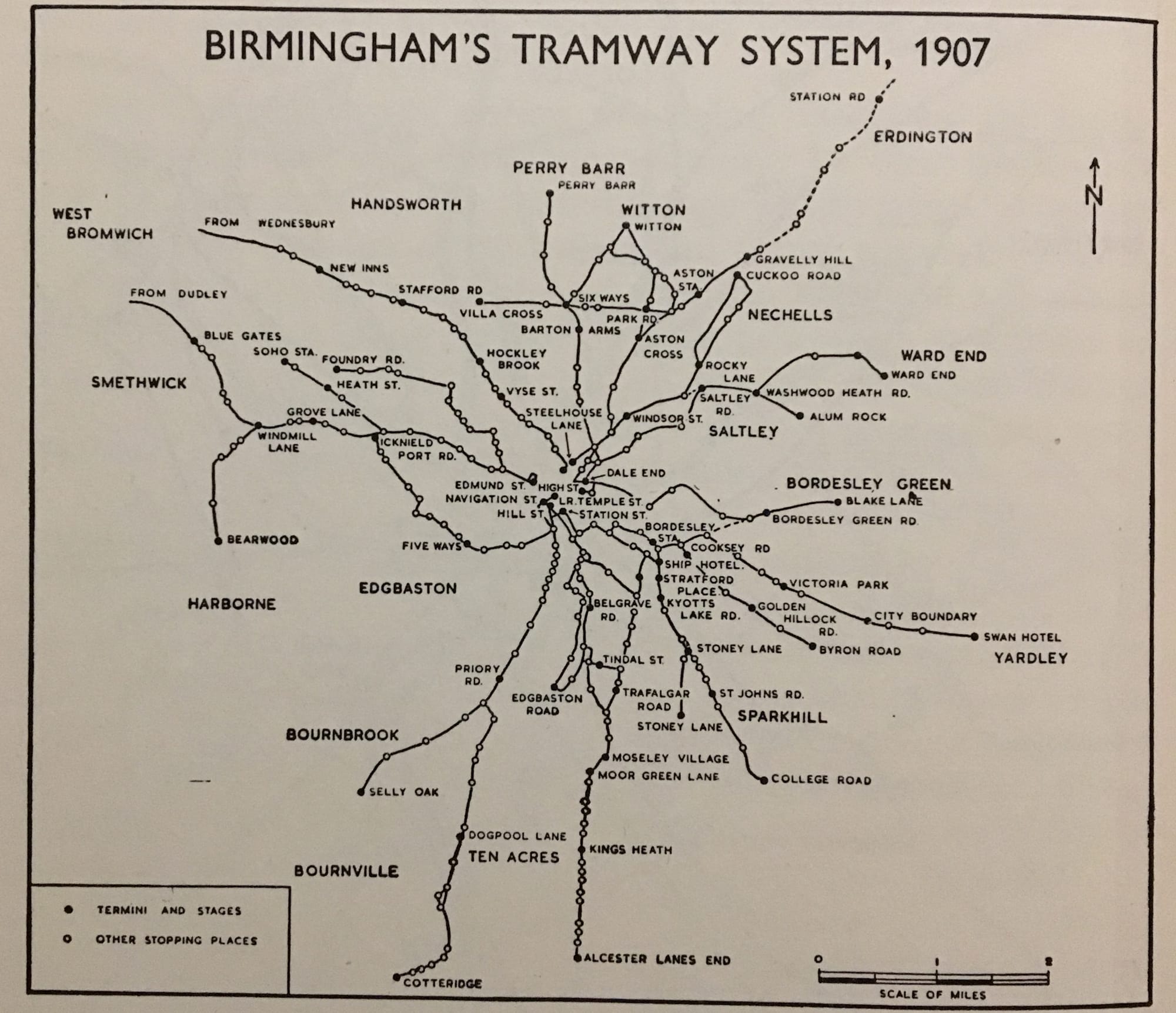

While suburban railways did drive growth in whole swathes of the ‘middle ring’ — Acocks Green, Tyseley, Stechford, Erdington — it was the tram network that really changed things, ‘filling in the gaps’ as it were. After municipalisation and the beginnings of electrification in the late 1980s, the network expanded rapidly. Trams took over from trains as the main commuter form, and as they were cheaper and more accessible, they meant that more ordinary workers could move further out of the core.

So associated were the trams with the new affluent working class, that Harborne (thanks partly to the Calthorpes) managed to prevent tramways ever reaching the area. Housing away from the old station remained relatively sparse and spread out.

This kept much of Harborne leafy, and kept parts of it undeveloped, primed for a new type of housing, the more lavish 1930s detached, that would crop up a few decades later around, say, Lordswood Road.

The railway itself closed in that decade; with its single line, slow trains and meandering route, it could not compete with the more direct buses, or the cars increasingly owned by the more affluent workers. It remained a freight line — partly because it served the M&B brewery at Cape Hill — for a few more decades.

Meeting modernity

Nevertheless, Harborne’s combination of dense terraces surrounded by larger homes meant that it always retained a certain cachet, one that made it ready for the urban gentrification that began in the 1980s, when people began viewing Victorian terraces as desirable rather than ripe for demolition. Proximity to the universities and the hospitals helped too, of course.

Modern Birmingham is often thought of as a city dominated by the car. And while there is some truth to that, it’s also a massive generalisation. It’s impossible to understand why the place is the way it is without appreciating the role of the railway and the tram; the suburbs they served are still generally the most popular.

Indeed, much of the 1930s development that created the endless semis that form the city’s outer belt was also oriented around the tram system; at the time, car ownership was rising, but it was still not mainstream, even for better off workers. The inner city and the overspill estates are the real products of the motor age, where the warrens of terraces and back-to-backs were replaced by housing built with the road, car and bus in mind.

It’s a generalisation in other ways too. The infamous Beeching report of 1963 is blamed for devastating Britain’s railway system. (The report’s a bit of a misnomer; Beeching was just a civil servant, it was really led by the Conservative Transport Minister Ernest Marples, who owned a road construction company and ended up fleeing to Monaco to avoid tax.)

The Beeching axe, as it was called, did not swing especially heavily in then-booming Birmingham – although his decision to shutter Snow Hill did lead to the destruction of one of the city’s great Victorian buildings. The closure of the misleadingly named North Warwickshire line — which runs into Moor Street from Stratford via Henley, Shirley, Yardley Wood and Hall Green — was avoided after a local campaign. The low-level line to Wolverhampton was not so lucky, although it has now re-opened as part of the Midland Metro.

Similarly sized Manchester, then struggling economically, lost multiple lines and over 100 stations. But the resulting lack of intra-city transport links made it easier to justify trams to the Treasury during the north western city's nineties revival. They were also cheaper to build as the corridors were all there, ready to be reused.

What’s most surprising is that, as a result of all this and the creation of the Cross City Line in the 1980s, Birmingham has the most used suburban network — and more peak-time commuters into its centre — than anywhere else in England outside London.

The latest figures show that an average day in the autumn of 2024 saw around 42,000 commuters arrive at the morning peak, compared to 29,000 in Manchester, 24,000 in Leeds and 16,000 in Liverpool. What’s more, while still below the pre-pandemic peak of 54,000, it was up 13% on 2023 — the biggest increase of any English city outside London. (During the decade before the pandemic, it had also outpaced other regional cities in the increase in rail commuting).

These figures feel very much at odds with Brum's self-image as a city uniquely dependent on the car, uniquely deprived of public transport. This may be because the inner city isn’t well served, or because — as the network is still not that extensive given Birmingham’s size — there are quite large parts of it not served at all. Frequency and train capacity are issues too.

Discussion of how to improve the city’s transport tends to focus on the tram, but perhaps, given the city’s geography, thinking more creatively about the train could reap rewards. Freight lines, such as the ‘Lifford Curve’ or the Stechford-Aston link, might offer orbital systems or Elizabeth Line-like options. Tram-trains on existing routes could offer a quick way to increase frequency. Certainly, the city should think more carefully about how to plan development around train lines, new and old.

After all, away from the city centre, the bits of Birmingham that are valued the most, that have the sort of housing that people aspire to, are those that, like Harborne, are products of the railway age. And while the Harborne Walkway might, today, offer an escape from the city, it’s actually a route that explains much about why Brum is the way it is. Perhaps it also offers some hope for a more humane and pleasant city in the future, too.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can get in touch at grace@millmediaco.uk or visit our advertising page below for more information

Comments