Dear Patchers — this morning we told you the general election announcement had thrown a spanner in the works for the story we had planned to publish today. Well, things move fast in the media and we are happy to say we can now share the article with you.

Below is an incredibly moving story about a young man, an asylum seeker, who took his own life in a hotel in Birmingham late last year. The details have only been uncovered thanks to investigative reporters at Liberty Investigates and the story is a joint exclusive for The Dispatch and iNews.

Investigation: A teenager took his own life in a Birmingham hotel. Now, his family want answers

By Aaron Walawalkar, Harriet Clugston and Kate Knowles

On 10th December 2023, as most teenagers were winding down from term time ready for Christmas, one 19-year-old lay unresponsive in a Birmingham hotel room. His older brother discovered his body and a staff member called the emergency services. Nothing could be done to save him.

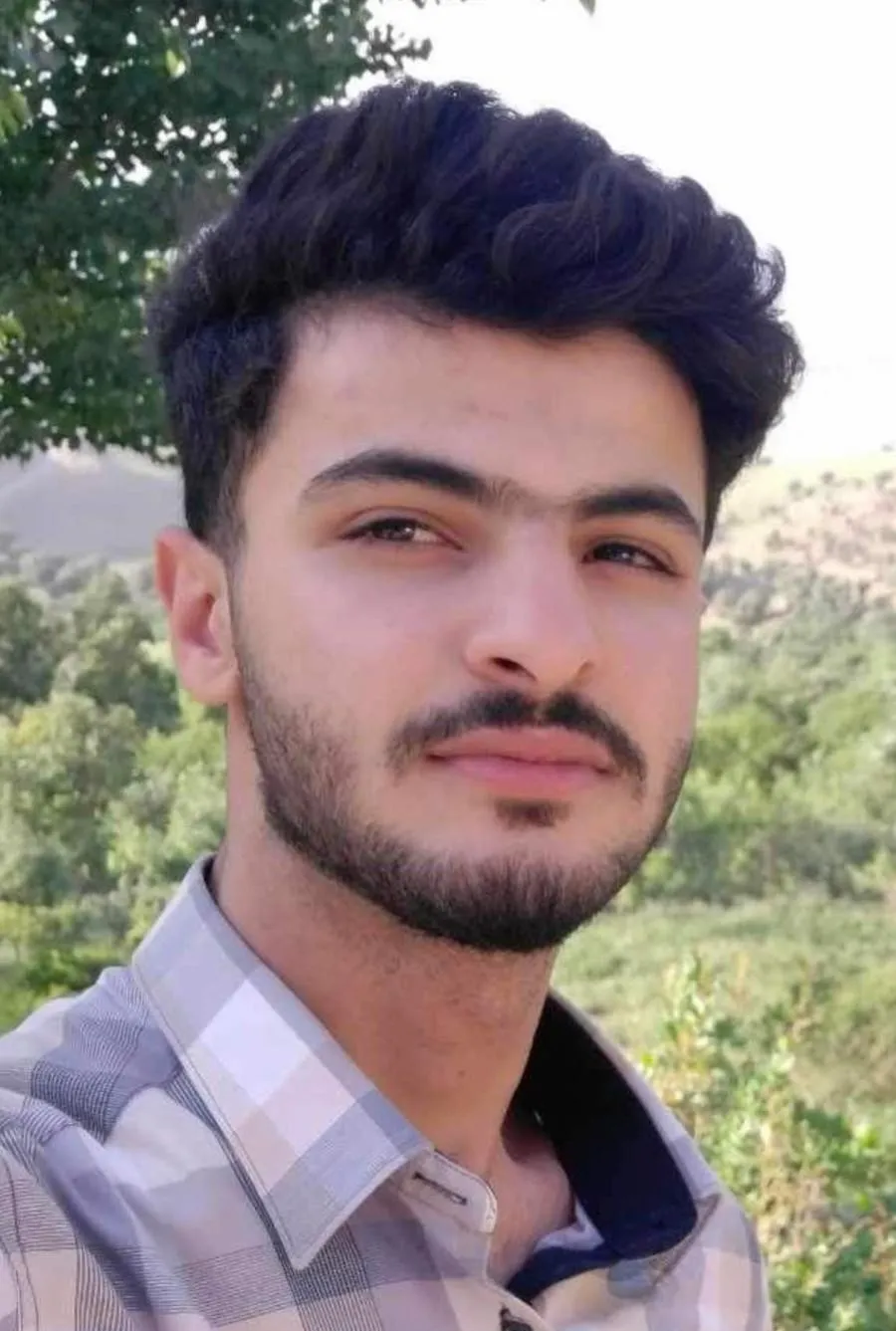

Ismael Maolanzadeh was a Kurdish-Iranian national. He was a vocal protester against the Iranian government, in particular its death penalty and discrimination of women. He had fled his home amid the risk of possible reprisals and arrived in the UK on a small boat last August. He was ordinarily a “joyful, happy boy”, according to his brother Mustafa, 23. But after living in accommodation that Mustafa describes as more like a “prison”, Ismael sank into a deep depression.

The Home Office initially refused to reveal Ismael’s name, or where he died. This information was only uncovered by Liberty Investigates, the editorially independent journalism unit of Liberty, the human rights organisation. Using anonymised data released under freedom of information laws, we traced the incident to Birmingham.

What we discovered is cause for concern. It appears that at the time of his death, Ismael’s application for asylum had effectively been paused while the Home Office explored the possibility of moving him out of the country. What’s more, Birmingham Coroner’s Court cancelled a hearing into Ismael’s death that would have been open to the public and media, and instead chose to conduct a private inquest, relying on just one witness statement (from a housing officer responsible for welfare checks at Ismael’s Serco-run hotel) and a brief police report (from officers who attended the scene) to determine how he died.

The coroner’s official verdict ruled Ismael’s death a suicide. A Record of Inquest Certificate detailing the conclusions of the inquest heavily implies his depression was down to a break-up with his long-distance girlfriend. It makes no mention of his asylum status.

“He had no known mental health concerns but was understood to be upset by a recent relationship breakdown,” it reads. The verdict relies on the police report, which states that Mustafa had told them Ismael had been upset following a phone call with his girlfriend the day before he died.

The housing officer said in their statement that there was “no suggestion” Ismael was suffering from mental health problems or feeling suicidal. However, they admit they “had not had any dealings” with the teenager in the four months he had been housed at the facility.

Deborah Coles, executive director of the charity INQUEST, which provides expertise on state-related deaths, says she struggles to understand how a “very quick” written inquest could be justified for a vulnerable young person under the state’s care. She adds that the coroner’s failure to question the Home Office or look into safeguarding of asylum seekers had “left an accountability gap” that was “unlikely to be an isolated incident”.

Meanwhile Mustafa, who lodged his own asylum claim nine months ago, says he is still yet to have a substantive asylum interview himself. When we speak, he is dismayed by the coroner’s verdict. He and his brother were inseparable; he says he was unaware of any relationship issues his brother was facing. He knew the young couple would occasionally fight, but adds they would usually get back together the next day. Ismael was 19 years old — this all seemed normal to his older brother.

A tall young man with short, black hair and a wispy moustache, Mustafa is polite and friendly when he speaks to us through an interpreter. He is soft spoken and sits slightly hunched over as though nervous. As he arrives at the point in the story where he found Ismael’s body, he begins to tear up. He lets out a sigh and asks to take a break.

When we start again, he recalls being asked by police to confirm if his brother had a girlfriend. Officers then told him they’d take Ismael’s phone and check if they were exchanging messages. The phone has never been returned, Mustafa says, which is disappointing because he wants to check it himself for messages from his brother (Ismael didn’t leave a suicide note).

He paints a bleak picture of life inside the hotel. “You spend your time, 24 hours, between four walls and there's nothing you can do,” he says. “You don't have money to go out. My brother was very, very active. He was always participating in the protests. He had a lot of energy. But once he got here, it's like all this thing has been taken away from him.”

Ismael got depressed. His brother was always trying to cheer him up. "It's not going to be like that forever. It's temporary’,” he would tell him.

Mustafa was not able to contribute evidence or pay tribute to his brother at the inquest, despite initially being invited to the hearing by the coroner. He only realised the hearing had been cancelled after he asked Serco to check if an interpreter would be provided for him. When we tell Mustafa that we have received documents from the coroner’s court, including the inquest certificate and a witness statement by the Serco housing officer that he is yet to see, his expression turns to one of shock and frustration. “Since what happened — no one [has] bothered to explain or to give me a clue about what's going on,” he adds.

Documents obtained under information laws suggest that, at the time of his death, Ismael’s application for asylum had effectively been paused while the Home Office explored moving him out of the country. His was recorded as a “TCU case” meaning the Third Country Unit team was responsible for deciding if his claim was inadmissible under various new legislation.

Home Office guidance suggests the team should secure an agreement with a safe third country to accept a person within six months of their claim being registered, to avoid them being placed in a “limbo” position where their claim goes unprocessed. Rwanda is so far the only country with which the UK has an agreement to remove asylum seekers en masse, but at the time Ismael’s case was lodged, removals were impossible following a Supreme Court ruling in November which found the Rwanda plan unlawful. Since then, the government has agreed a new treaty with Rwanda and brought forward new legislation – the Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Act, designed to override any legal obstacles and declare the country to be safe.

Zoe Bantleman, legal director of the Immigration Law Practitioners' Association, says the government’s inadmissibility policy has created “a large and ever-growing black hole of people left in permanent limbo”.

She says: “The vast majority are unremovable to countries with which they have no connection, but they are condemned to a life without hope of obtaining sanctuary and denied the opportunity to build a meaningful life from the fruits of their own work.”

Local politicians and law practitioners have added their voices to the call for a government investigation into Ismael’s death. Labour Birmingham City Councillor David Barker says: “The fact a young life has been lost and another young life will be scarred forever by the tragic suicide of their teenage brother should alone be enough for an inquiry into where the Home Office went wrong.”

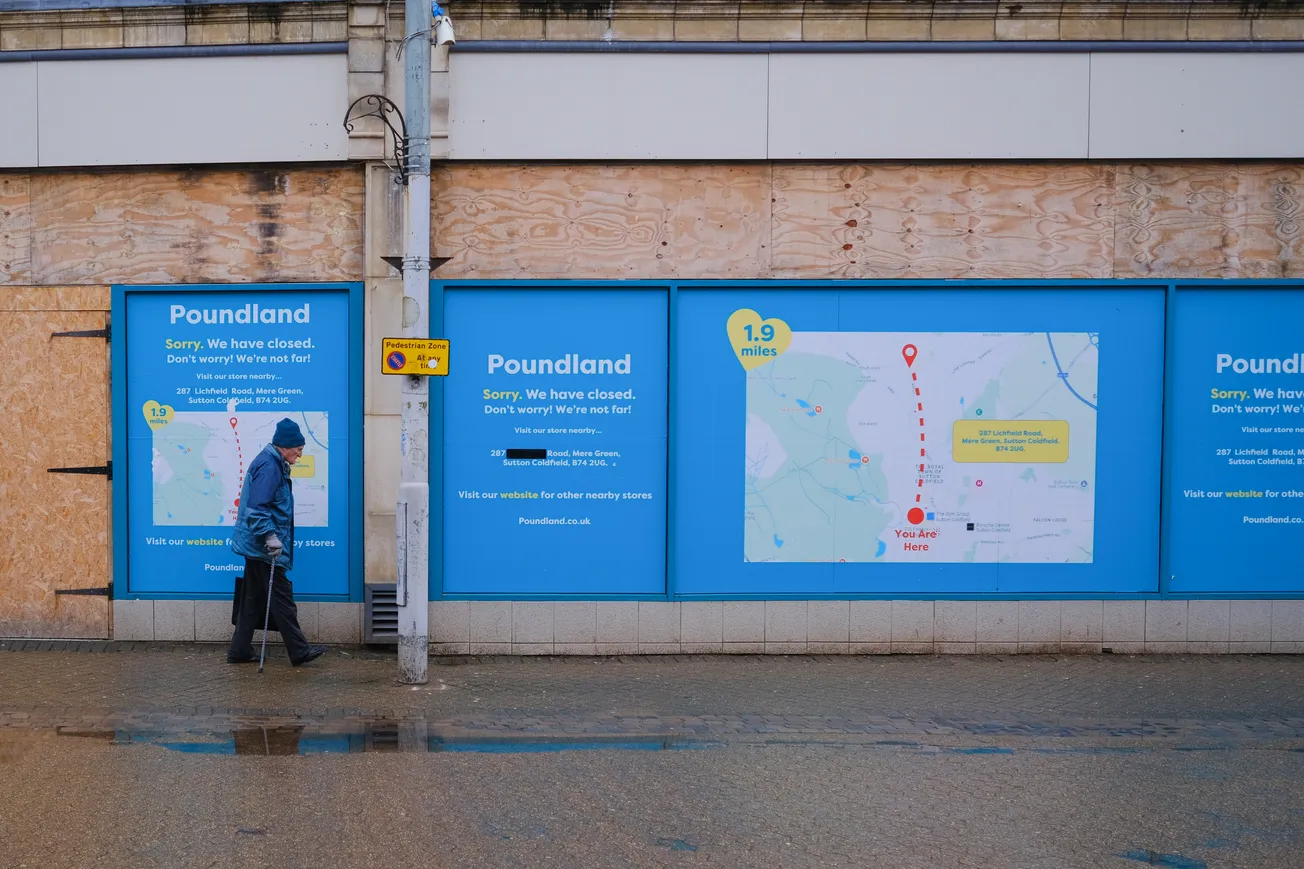

He says he has seen many hotels like these in Birmingham up close, which are now being used as temporary accommodation for months, if not years, as the housing shortage means we have nowhere else to place asylum seekers.

The Labour MP for Hall Green Tahir Ali and three Birmingham Lib Dem councillors — Ayoub Khan, Roger Harmer and Izzy Knowles, the latter two standing at the general election — are also calling for an investigation. Martin Hoare, a Birmingham-based Solicitor Advocate with Higher Rights of Audience said:

“By keeping asylum seekers in positions of uncertainty and housing them in temporary accommodation for long stretches of time, the Home Office is creating incredibly stressful conditions for people who are already vulnerable. Add to this the risk of being sent to Rwanda and it is plausible that the circumstances could have contributed to this young man's death."

A Home Office spokesperson says: “This was a tragic incident, and our thoughts are with everyone affected. We take the welfare of asylum seekers extremely seriously.” They add that their approach “at every stage” is to ensure that “all needs and vulnerabilities are identified and considered, including those related to mental health and trauma”.

A spokesperson for Serco tells us the company was not responsible for healthcare, and that its housing officers are not welfare support staff. They call the death “a tragedy” and say that their thoughts are with family and friends.

Today, Mustafa lives at a different asylum hotel. He says it constantly reminds him of his brother’s fate. He has only been registered with a counsellor this month, as mental health outreach services to the hotel were cut in January this year due to lack of funding.

“Every time I open the door, the picture of what happened — it's in front of my eyes. I can't get it out of my head,” he says. “So that's why I don't like hotels. I'm kind of traumatised.”

Comments