My school bus used to go past the Pebble Mill TV studios in Edgbaston every morning. The vast glass front meant that the main foyer could be seen from the road. If it was being used for filming – which was often the case – we would shout and wave, hoping to be caught on camera. We never were.

The fact it was a major television studio – home to dramas and national news shows such as Pebble Mill at One, Telly Addicts, Howard’s Way, Good Morning with Anne and Nick and Juliet Bravo – gave us the impression, however vague, that we were living in a city that had some importance in the world.

The building, designed by the great post-war Brummie architect John Madin, will live on as one of the city’s icons, despite being demolished in 2005, taking with it the BBC’s once-significant presence in Birmingham.

But there was an earlier incarnation of Pebble Mill. In the 1970s, this corner of the city had been home to the most radical, barrier-breaking and inventive television drama department in Britain; an almost autonomous unit within the BBC: English Regions Drama.

This department of Pebble Mill would produce the first TV dramas directed, written by and starring black, Asian and gay characters, often way before anything made in the capital, helping to define the liberal and multicultural – and sometimes conflicted – country that was emerging in that decade.

In the process, its output would lead to many of the country’s most beloved actors, writers and directors – Alison Steadman, Norman Beaton, Saeed Jaffrey, Stephen Frears, Mike Leigh, and Ian McEwan – making their TV debuts (or at least their first major productions).

The BBC had introduced a new regions policy in the late 1960s, aimed at distributing more programming outside London. This led to new centres in Bristol and Manchester as well as Birmingham, although it was the latter which would prove the largest and most productive, at least for the first decade or two.

When Pebble Mill opened in 1971, on land leased from the Calthorpe Estate for peppercorn rent, it was the most sophisticated in the country, the largest outside London, and the first to combine TV and radio operations under one roof. It was conceived as the regional counterpart to the Television Centre in Shepherd’s Bush.

It wasn’t the first modern studios in the city though; ATV had opened its studio complex on Broad Street – now the Arena Central development – in 1968, claiming it to be the first purpose-built colour studios in Britain. This prolific output may also have been a reason for the investment at Pebble Mill.

It brought together BBC Midlands operations that had previously been split between various locations – Broad Street, Carpenter Road in Edgbaston, and the former Delicia cinema in Gosta Green (which survives as part of Aston University’s Energy and Bioproducts Research Institute).

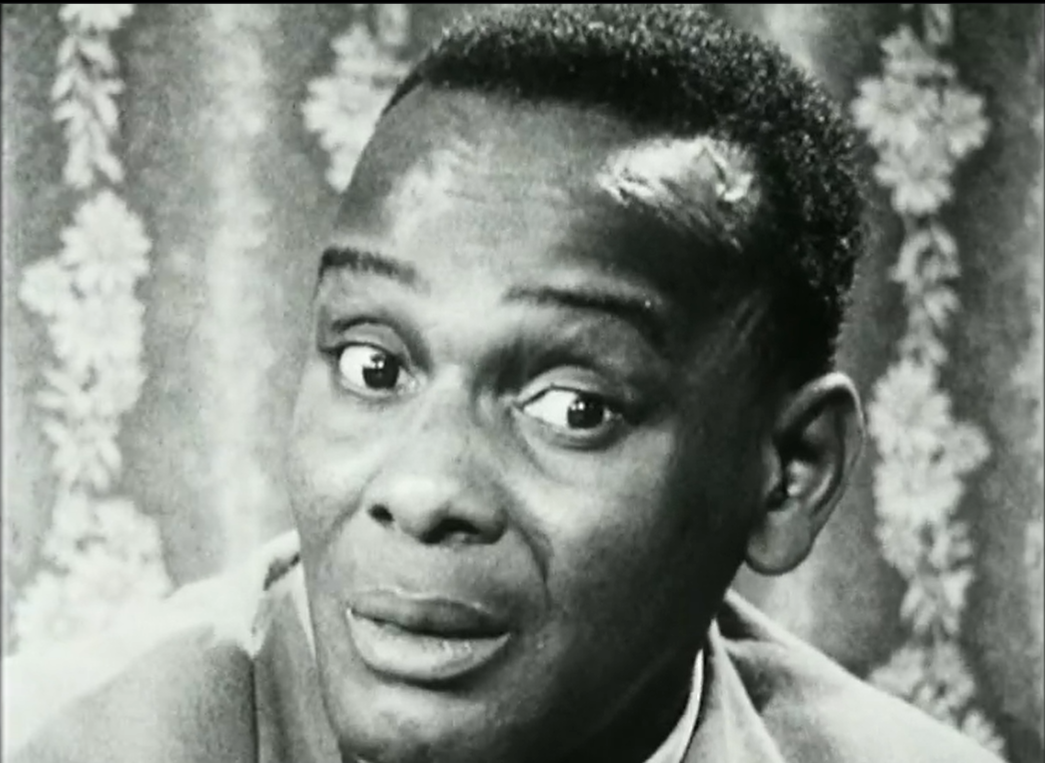

The latter had already become famous for innovative drama. Its output included The Dark Man (1960), in which Earl Cameron played an immigrant taxi driver and Rainbow City (1967), a six-part series starring Errol John as a solicitor living and working in Birmingham and married to a white woman (played by Gemma Jones, later Madam Pomfrey of Harry Potter fame). These were the first British TV dramas and series, respectively, to feature black lead roles; both actors would go on to become television mainstays.

This legacy may be why the producer David Rose – who had already made his name as a director of documentaries and then the groundbreaking Merseyside-set police series Z-Cars – was asked to set up the new drama department at Pebble Mill.

English Regions Drama was given the remit of producing innovative drama based on hard-hitting, socially aware and distinctly non-metropolitan themes – and using young and relatively inexperienced directors and writers. There was a determination to create a ‘sense of place’ deeply embedded outside the capital.

Dr Vanessa Jackson, a former producer who is now an Associate Professor at Birmingham City University, explains: “There was a lot of excitement about Pebble Mill at the time, it was the place to be. There was a team of young producers and editors, who literally had permission to be experimental, permission to fail. That just wouldn’t happen today.”

The fact the unit was free of the restrictions, bureaucracy and hierarchies of the BBC in London also gave it an extra edge. It was also assisted by the burst of creativity that occurred in Birmingham from the late 60s to the late 70s.

The Midlands Arts Centre was already well-known, notorious even, for its experimental theatre, while the Birmingham Art Laboratory – which had taken over the former BBC studios in Aston – had become nationally famous for its artistic ‘happenings’. Moseley, with many of its large Victorian houses converted into bedsits, was becoming a byword for bohemianism and alternative lifestyles.

In 1972 the Studio opened at the Rep and quickly gained a reputation for cutting-edge drama. David Edgar, the product of a Birmingham family which had connections with the theatre and indeed the early days of the BBC in the city, would become resident playwright in the mid-70s, before gaining national fame.

This creative context, and the ethos and ambition of Rose and the wider English Regions Drama team, are evident in many Plays for Today. These were one-off films broadcast on Thursday night – often featuring themes that proved controversial.

Among Pebble Mill’s contributions were Mike Leigh’s 1975 TV debut Nuts in May, a comic piece set in a Dorset campsite which set the tone for the director’s career; it also features two exaggerated Brummie characters, perhaps not a coincidence.

Gangsters (1975) was also typical of the experimental approach at the unit. The director, Philip Martin, was given a grant to live in Birmingham for three months and come up with a script at the end of it. In the end, he opted for a hard-hitting crime series set in the city’s multicultural underground, centring on a former SAS operative sent to work undercover.

Later turned into two series, it depicted racism and violence with an honesty that is perhaps shocking by today’s standards, but was also groundbreaking in its multiracial cast (including a breakthrough role for Saeed Jaffrey). The characters come from all moral compass points regardless of racial background. Stephen Knight’s recent This Town, with its decommissioned army officer going undercover, seems to echo some of its themes.

But the most celebrated of the Pebble Mill Plays for Today is undoubtedly Penda’s Fen (1974), written by Bromsgrove-born David Rudkin and directed by Alan Clark, who was later responsible for the extraordinarily raw Scum and The Firm.

In recent years it has become a cult classic, the subject of cinema screenings, talks and new books; indeed, it is hard to think of another vintage TV film which has received anything like this level of attention in recent years.

According to the Guardian, it is “an unforgettable hybrid of horror-story, rite-of-passage spiritual quest and vision of an alternative England that has been hailed as one of the most original and vauntingly ambitious British films of the last half century.”

A deeply odd, almost psychedelic film, it is set in the Worcestershire village of Pinvin – a corruption of Penda’s Fen. It follows the conflicted figure of Stephen Franklin, who is torn between his conservative mindset and his emerging homosexuality; in a series of visions, he meets angels and demons, as well as historic figures from the Midlands, including the composer Edward Elgar and Penda himself, the last pagan Anglo-Saxon king of Mercia.

The play also betrays how much Rudkin had detested King Edward’s School; a deeply authoritarian, bullying teacher lectures the class from a model of the Pugin-designed chair-and-desk set used by the school’s chief master.

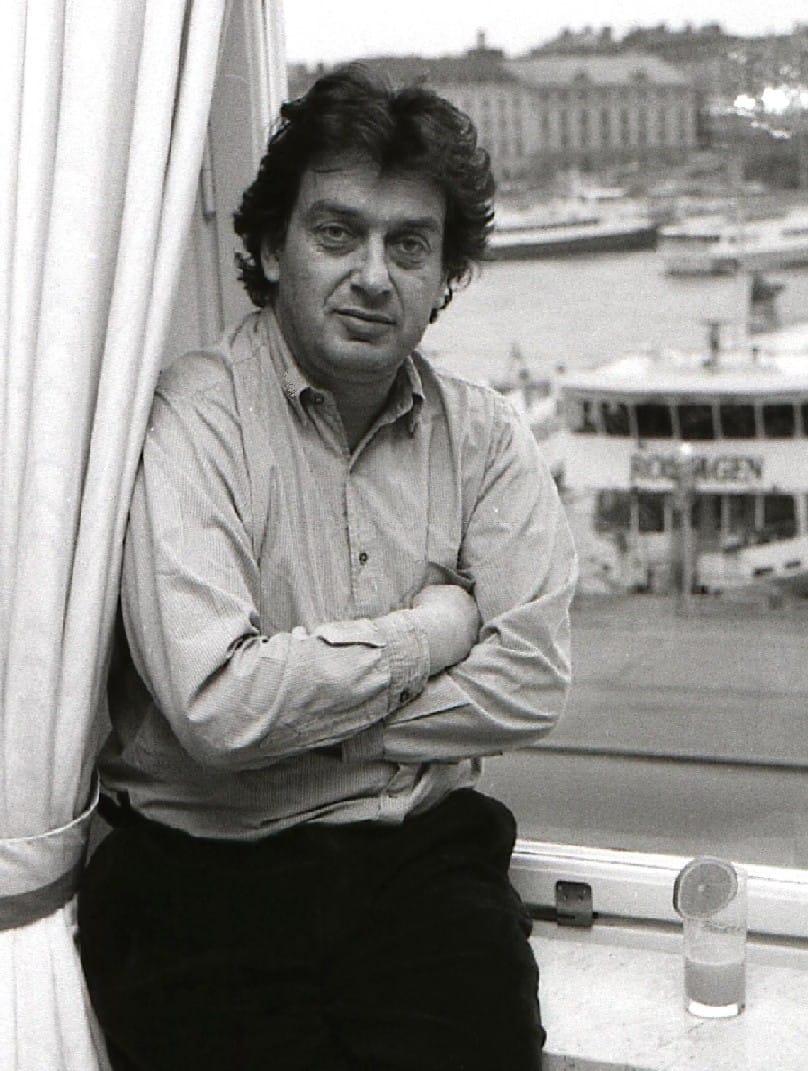

Interviewed in the 2000s, the playwright David Hare felt the film summed up the freedom and experimentation of Pebble Mill drama at the time: “When I saw Penda’s Fen I just couldn’t believe it. And that is the whole BBC Birmingham culture right there, which was David Rose letting people do what they wanted and nobody in London knowing what was going on.”

Hare would go on to make his TV-directorial debut at the studios with 1978’s Licking Hitler, a Play for Today set in a wartime propaganda unit based in a Warwickshire country house. It won a BAFTA for best single play.

Slightly less famous, but perhaps even more radical, was the anthology series Second City Firsts – a number of one-off dramas featuring new writers and/or new directors. The list of debuts provided by the series is breathtaking: Alan Bleasdale as director of Early to Bed (1975), Willy Russell’s King of the Castle (1973), Ian McEwan as writer of Jack Flea’s Birthday Celebration (1976), Pete Postlethwaite in the science fiction short Thwum (1975), and Julie Walters in Club Havana (1975).

In Girl (1974), two army officers – Alison Steadman and Myra Frances – take part in the first same-sex kiss on British television, almost two decades before the more famous Brookside encounter.

Predating Second City Firsts but sharing its team, was A Touch of Eastern Promise (1973), written by half-Indian script editor Tara Prem. Set in Balsall Heath, it is the tale of a young Indian Brummie who dreams of meeting his favourite Bollywood star – and the first drama in Britain to have an entirely South Asian cast.

Prem had noticed, on her daily walk from Moseley to Pebble Mill, how the ethnic mix of the city was changing, while television was not, and had become determined to rectify that. The lack of appropriate actors proved a challenge, and led to the team walking around Balsall Heath asking random people if they would like to act in a drama.

Indeed, following on from the Gosta Green tradition, the breaking of racial boundaries became something of a speciality of the drama unit. Stephen Frears, who would later become one of Britain’s most famous directors with the likes of My Beautiful Launderette and Dangerous Liaisons, made his TV debut with Black Christmas in 1977.

Written by the British-Guyanan Michael Abbensetts – one of the most celebrated black playwrights of post-war Britain – it was unusual in presenting a black family in an everyday domestic setting. It focuses on the tensions around a Christmas family gathering and the immigrant experience and features Norman Beaton, later famous for his lead role in Desmond’s.

Abbensetts got to know Handsworth while working on the play and proposed a new concept to Rose: a drama series based around the area’s multicultural inhabitants. What followed was Empire Road, the first British TV drama series to be directed and acted by a predominantly Black and Asian cast – and the first time a black playwright had been given a series commission.

Run as two series in 1978 and 1979, it was effectively a soap, with the lead character – patriarchal local shopkeeper Everton Bennett – played again by Norman Beaton. The cast also included Joseph Marcell, who would later star in The Fresh Prince of Bel Air, and Rudolph Walter, perhaps most famous for later playing Patrick Trueman in Eastenders.

It is hard to exaggerate how radical Empire Road was. At a time of racial and political tension, showing ordinary Black and Asian people dealing with everyday problems, and depicting them as parents, teachers or business owners, was something that most British viewers had simply not been used to.

According to Jackson, there were huge amounts of letters received from across the country, praising the fact that they had seen their communities on TV for the first time.

Pebble Mill continued making drama in the 1980s and 1990s, but it never matched the output of its first decade. Nevertheless, productions such as Malcolm Bradbury’s The History Man, Alan Bleasdale’s Boys from the Blackstuff, and a number of plays from feminist playwright Michelene Wandor continued to be produced in Edgbaston – despite the first of these famously being set in the North East.

By the 2000s, though, Pebble Mill’s facilities were becoming outdated and the building was struggling with some structural issues. Programming was drifting back to London – with some old Birmingham hands arguing that the capital had become jealous of the facilities and freedom in the Midlands.

In 2004, as part of Greg Dyke’s cost-cutting measures, the decision was taken to close Pebble Mill. This hit the city’s broadcasting industry hard, particularly as Central had made the decision to close its Broad Street studios in 1997.

Birmingham was promised major new investment, but ended up with a much smaller studio in the Mailbox and a Drama Village in Selly Oak, which proved marginal in the corporation’s overall setup. The decision was clearly made – implicit or otherwise – to radically scale down operations in Birmingham and concentrate a new regional drive on Manchester (or rather Salford).

According to a Hansard debate in 2015, between 2009 and 2015, BBC spending in the Midlands fell by 35%, despite rising by 35% outside London in general. In the North of England, spending rose by 217%.

Ian Francis, director of the Flatpack Festival – which has screened many of the films produced by English Regions Drama over the years – says: “The loss of Pebble Mill also meant the loss of a massive pool of skilled freelancers, and the number of films and TV shows coming out of the West Midlands plummeted.”

The BBC’s decisions in the 2000s have left Birmingham with a smaller media sector than many other big cities, making it more difficult to make the case for investment by the likes of Channel 4. It has also amplified the impression in some circles that it has always been a cultural backwater, something not helped by the fact that Pebble Mill’s role in forging modern Britain is not well known or publicised.

The situation has recovered a little since the 2010s. But still, in 2023/24, just £128m was spent by the BBC in the Midlands, the lowest of any region, despite it providing the largest slice of TV licence revenue (£934m).

The whole legacy of Birmingham’s TV dramas, all that inventiveness, rule-breaking and taboo-busting, is nothing but a memory. The days when mainstream drama and daytime TV could be seen by schoolkids from the top deck of the buses on the Pershore Road – when the studios provided 15% of all BBC output - have long gone; hospitals now stand on its site.

Birmingham is in many ways a more pleasant and liveable city than in the 80s, but it feels diminished by this loss, a less nationally significant place.

There is hope in the form of a new BBC presence in Digbeth as well as Stephen Knight’s Digbeth Loc. But as Francis says: “If we are looking to build a new golden age for production in the region, we could learn a hell of a lot from the approach that Rose and his team took – particularly in reaching beyond the usual suspects to support new writers, and trusting in their talent.”

Correction: an earlier version of this article suggested the West Midlands provided £934bn in TV licence revenue. This has been corrected to £934m.

Comments