Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Is fascism making a comeback? This question reverberated throughout 2025, with politicians and commentators across the west warning against the rise of the far-right. In January, Sadiq Khan wrote in the Observer that there were “echoes of the 1920s and 30s” today, and in June, Nobel Laureates and academics from around the world signed an open letter warning of “a renewed wave of far-right movements, often bearing unmistakably fascist traits”. In September, record-breaking numbers of people marched on London for Tommy Robinson’s Unite the Kingdom rally.

While fascism has mostly been kept from the political mainstream in Britain, it has had a significant number of supporters at times. Birmingham, and the wider West Midlands, have been pivotal to that story. To kick off 2026, we are publishing a series of three essays about key moments in the West Midlands during the history of British fascism. Following on from last week's essay on Oswald Mosley by Paul Jackson, academic Kevin Harris delves into the lesser-known far-right figure, Colin Jordan.

Outside far-right circles, historians or those with long memories, few people today will recognise the name Colin Jordan. But those who forget history are doomed to repeat it. And Jordan is a significant figure, for unsavoury reasons: the Black Country-born politician was the man responsible for the revival of neo-Nazism in Britain after World War Two.

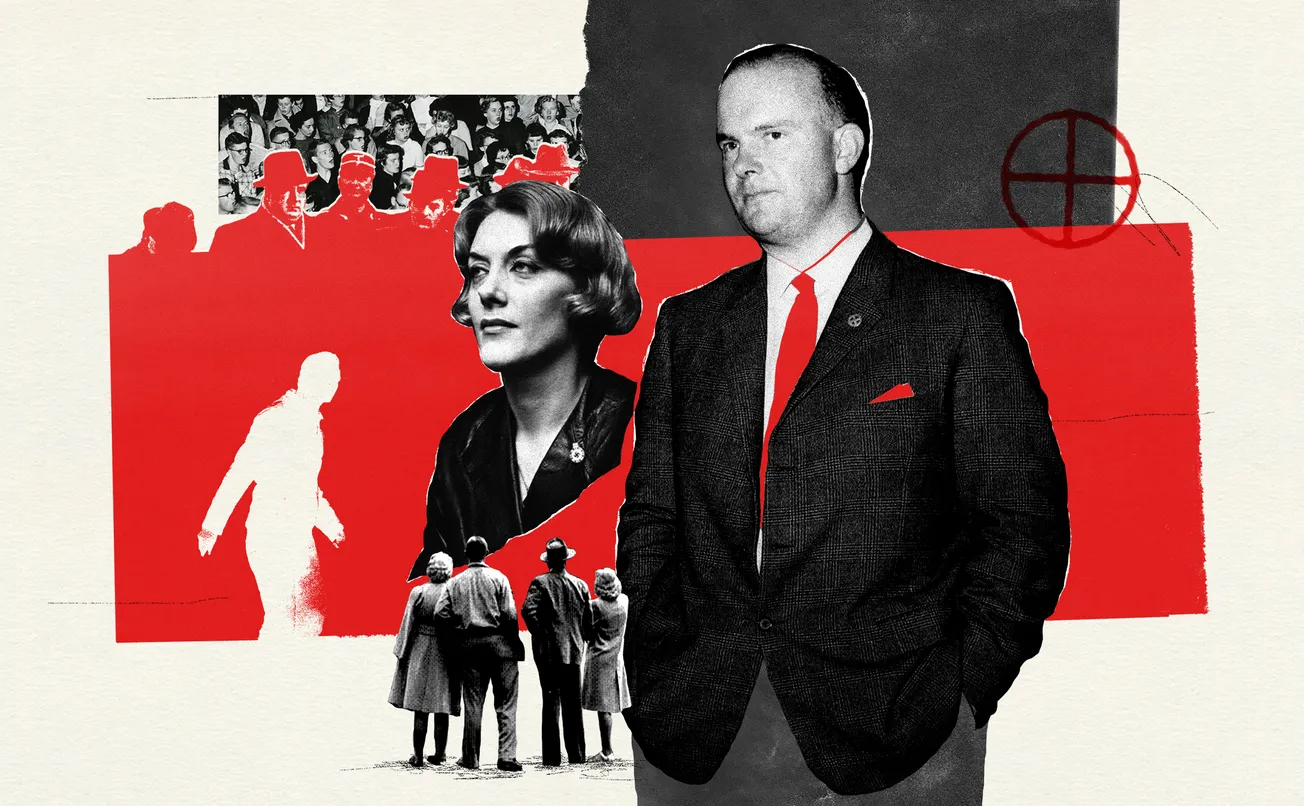

BBC viewers might recognise Jordan’s name: five years ago, he and his neo-Nazi wife — the niece of French fashion designer Christian Dior — were fictionalised in the BBC drama Ridley Road. The series tracks the real-life Jewish anti-fascist resistance movement in the 1960s, and while the series is set in London, Jordan’s hometown of Birmingham and the Midlands frequently serve as the backdrop for his extremism.

Although it’s comforting to believe that fascism has been relegated to the margins of history, Birmingham and the Midlands have long been both targets and sympathetic grounds for far-right groups, portraying immigrants as foreign invaders. Recent anti-immigration riots and arson attacks on hotels, including those in Solihull, Tamworth, and Birmingham city centre, as well as Trafalgar Square, highlight a noticeable resurgence in the far-right’s sense of national awakening and renewal of ‘Englishness’, a popular refrain among fascists.

Jordan is part of this history. He was an unapologetic antisemite and racist, who aimed to realise Hitler’s vision of a white supremacist, pan-European utopia. But how did Birmingham shape such a man?

The early years

Born in Smethwick in 1923 to middle-class parents, Jordan spent his formative years in the family home in the Warwickshire countryside. He experienced the height of British fascism through Oswald Mosley’s fascist newspaper, Action, smuggled into the classroom by another pupil. The teacher duly confiscated the paper; whilst this was possibly an isolated incident, it sparked an early interest in fascism, foreshadowing his future politics.

Jordan nostalgically recalled that a family holiday to Nazi Germany in 1937, during his teenage years, was the most influential experience in shaping his support for Nazi ideology. His parents may have held fascist sympathies, but they were hardly unusual in visiting or admiring Nazi Germany before the war. It is telling, however, that his mother remained a devoted supporter of his extremist politics throughout her life.

Jordan's fascist role model, however, was neither his parents nor the nationally renowned Oswald Mosley, but Arnold Leese, a fiercely antisemitic veterinarian from Lancashire obsessed with the supposed insidious Jewish conspiracy for world domination.

Despite winning a scholarship to Cambridge, Jordan patriotically joined the British military at 18 during the Second World War, requesting a non-combatant role away from the front lines due to his political views. He soon became attracted to Leese’s antisemitic writings, strengthening Jordan’s doubts about Britain’s involvement in what Leese believed was a ‘Jewish war’ aimed at destroying Aryan unity and strength.

Following the war, Jordan resumed his studies at Cambridge, where, in addition to earning a degree in history, he joined the university debating society and frequently debated antifascists. Graduating with second-class honours in 1949, he returned to Birmingham, working with and writing to various far-right groups to address “the coloured issue” in the city.

Throughout the 20th century, the city witnessed an increasing number of Irish, Jewish, Caribbean, and South Asian immigrants, attracted by the availability of industrial and manufacturing jobs. The far-right depicted these new communities as foreign invaders, claiming they were taking British jobs. Many white residents sympathised with this view, feeling displaced. Birmingham shop windows often displayed signs such as “No Blacks. No Irish. No Dogs”. The hostile atmosphere amplified sympathy for Jordan’s warnings about a supposed Jewish white replacement conspiracy, and he believed Birmingham would be his support base to launch a Nazi-inspired revolution.

Entering politics

During the 1950 general election, Jordan mounted an antisemitic campaign against Julius Silverman, a Jewish Labour MP for Erdington. After daubing antisemitic slogans on walls, he began cold-calling the small number of residents with telephones, urging them to vote Conservative and support a British candidate. The vandalism-and-nuisance-call campaign was reported in the local Birmingham news, though it was a failure: Silverman kept his seat. However, Jordan clearly developed a penchant for direct political action, and his various racist campaigns in the Birmingham area impressed Leese and his wife enough to leave their London house to him in their will.

Jordan quickly made use of the bequeathment. In 1957, the house became the headquarters of the White Defence League, a group he formed which aimed to “preserve the white race”. During the Notting Hill race riots a year later, Jordan attempted to capitalise on racial tensions by printing literature that incited violence, quickly becoming the media’s spokesperson for extremist views on immigration. In an appearance on the BBC’s Panorama in 1959, he advocated for a ban on white immigration and the forced repatriation of non-whites, regardless of whether they were born in Britain. Initially, he declared himself to the press as a proud fascist but later rejected the label outright, believing fascists to be too spineless on the issue of racial purity.

The White Defence League eventually merged with other far-right groups to form the original British National Party, where Jordan’s Nazi tendencies became clear. He argued that the party had become too soft on immigrants and Jews, which led to a split with fellow fascist John Bean (on political rather than ideological grounds) — Bean feared that open Nazism would hinder the party’s political prospects.

Jordan decided to found his own party, with its colours taped firmly to its mast. In 1962, he launched the National Socialist Movement with John Tyndall, the leader of another neo-Nazi group. It spread Leese's antisemitic gospel. Gaining support from George Lincoln Rockwell, the notorious leader of the American Nazi Party and de facto international mouthpiece of neo-Nazism, Jordan soon ingratiated himself within a global network of far-right extremists.

In July that year, Jordan staged his most infamous political stunt in Trafalgar Square, giving a lengthy speech in which he repeatedly stated that “Hitler was right” in his efforts to eliminate Jews and communists, and lamented Britain's racial decline. Surrounded by heavies from Spearhead — the paramilitary force he was attempting to form, modelled on the SA — Jordan unapologetically raised the Nazi salute, shouting “Sieg Heil!” while cries of “Nazi scum!” echoed from counter-demonstrators.

The police struggled to control the situation, and riots broke out between fascists and anti-fascists. Jewish protesters, arrested at the scene of the rioting, argued in court that they had been driven to madness by witnessing Nazism in Britain. Horrifyingly, these counter-protesters were still sentenced and fined. Jordan and Tyndall, meanwhile, received prison sentences but were later granted bail on appeal, prompting jeering from the public in the courtroom gallery. During sentencing, a member of Jordan’s group shouted, “We shall be back”, and they soon were.

The stunt brought Jordan to national prominence and notoriety, particularly considering the full horrors of the Holocaust were fresh in the minds of the public, following the execution of Nazi SS officer Adolf Eichmann the previous month. Media reports concentrated on the swastikas and public violence displayed, and the Observer published a double-page expose on the resurgence of fascism in Britain.

That was to be far from the last time that Jordan was in the newspapers. He had been splitting his residence between London and his mother’s home in Coventry, where he was hired as a teacher at a local school. Though he improbably maintained that his politics never influenced the classroom, local parents protested, leading to his dismissal in August.

Controversy over Jordan’s dismissal made headlines nationwide. As a member of the National Union of Teachers, he sought union funding to contest the decision. Although the organisation disagreed with his politics, its leadership begrudgingly acknowledged that he was entitled to the same benefits as any other member. However, nothing came of it. Jordan was never reinstated and was later expelled from the union, fuelling his claims in the press that he was a victim of state persecution.

Despite Jordan’s penchant for inciting violence, it took what would today be considered a domestic terror plot for him to serve prison time. Jordan again claimed he was the victim of a conspiracy against him. Two months after appearing in court over the Trafalgar demonstration, Jordan and Tyndall were found guilty of supplying their paramilitary organisation, Spearhead, with chemicals used in explosives. However, the arrests meant the chemicals were never combined to make the explosives. This kind of action had precedent among neo-Nazis in the Midlands: earlier that year, the police had caught a plumber, a BNP member in Balsall Heath, with explosives in his pocket. He admitted he wanted to “keep Britain white” by scaring “coloured people” into “going home” by planting explosives in their cars.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free issues of The Dispatch — including our Monday news briefings and the weekend read you're perusing right now — every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

‘World Fuhrer’

Obsessed with all aspects of Nazism, Jordan’s activities ranged from theatrical public displays to private, mystical, and bizarre rituals. He often held secret pagan-like ceremonies in forests, venerating Hitler and inviting international neo-Nazis as honoured guests. During a ceremony in August 1962, Rockwell and a cadre of international neo-Nazis burned a large wooden sunwheel, a pagan symbol; sang the Nazi anthem; and formally recognised Jordan as the new ‘World Führer’, a title which was unceremoniously removed following his imprisonment.

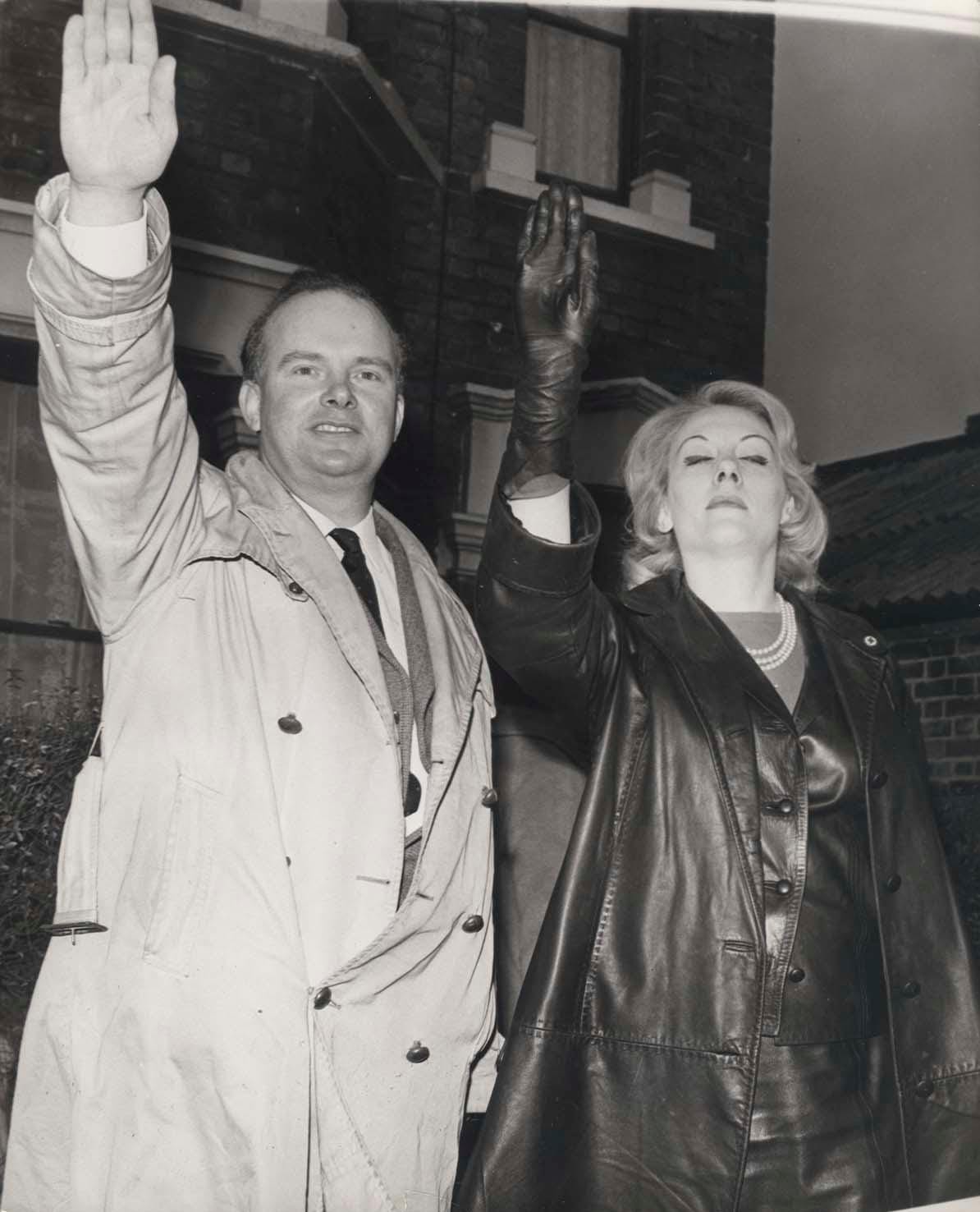

Jordan’s obsession with Nazi mysticism extended to his brief marriage to Françoise Dior in October 1963, arranged within weeks of the couple meeting after Jordan's release from prison. Dior, who was active within an international network of National Socialists, was possibly more fanatical than Jordan. Following a civil ceremony in Coventry, the couple held a ritual at Arnold Leese House, which involved cutting their ring fingers whilst declaring that they were of good Aryan descent. Their blood mingled and dripped onto a copy of Mein Kampf, the bizarre rite ending with cries of “Heil Hitler”.

The marriage received extensive coverage in the national press, sparking controversy within the Dior family. It also caused an irrevocable rift within the NSM: Dior had previously been engaged to Tyndall but jilted him in favour of Jordan. However, the marriage was unhappy, and Dior soon sought a divorce, claiming that Jordan was neither manly nor Nazi enough for her. Jordan tried to mend their relationship, but Dior soon took another lover from the party.

The bitter divorce and subsequent damage to Jordan’s reputation in Nazi circles marked his decline as a credible leader. After a further spell in prison in 1967 for breaching the Race Relations Act, he ultimately destroyed any remaining status among the far right in 1975 when he was convicted for shoplifting red knickers from a Tesco in Leamington Spa, after which he became a figure of fun.

Retiring from formal party membership in the 1980s, he spent his last years printing literature for various neo-Nazi groups, often centring on Holocaust denial and supposed white degeneration through interracial marriage.

His belief in a Jewish world conspiracy, the supremacy of the white Aryan race, defended through violent means, terror, and the righteousness of Hitler’s mission of world domination, changed little from his speech in Trafalgar Square until he died in 2009. Jordan remains venerated as a fallen hero by small circles of extremists on Telegram, primarily for his support for violent confrontation and unwavering commitment to fascist ideas. Yet during his active years, he encountered more opposition than supporters at public meetings. Reactions within the far-right were mixed: Mosley branded Jordan part of a lunatic fringe after his own ban from Trafalgar Square and difficulties in organising outdoor meetings post-Jordan’s stunt, whilst John Bean regretted having supported him, though not the cause. Yet, Jordan’s strongly antisemitic message resonated widely and became a unifying theme for post-war far-right groups — and remains so today.

In hindsight, Jordan is best viewed as an extreme expression of widespread racial tension and white immigration anxiety in Britain during the 1950s and 60s, driven by a longer tradition of intolerance, which subtly influenced reactionary mainstream politicians to shift further right in response to populist demagoguery. This influence was evident during the 1964 general election campaign when Conservative politician Peter Griffiths unseated incumbent Labour MP. Griffiths' campaign focused on anti-immigration talking points, with one particularly racist slogan — “If you want a n-word for a neighbour, vote Labour” — grabbing national headlines. Colin Jordan claimed to have directly contributed to Griffiths' victory by fuelling racial tension with his own campaigning in Smethwick in the run-up to the election.

Four years later, Wolverhampton MP Enoch Powell would make his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech, and in 1979, soon-to-be prime minister Margaret Thatcher spoke during a televised interview amid the general election, about people’s fears of “being swamped,” highlighting anti-immigrant sentiment as an effective election tactic.

Today's far-right seems to have learned from Jordan’s example and failure. Openly displaying Nazism is political suicide. However, soft-pedalling fascist ideas as acts of national pride, and claiming to hold governments accountable for not addressing immigration concerns, continue to play a more crucial role in expanding the limits of acceptable political discourse. Contemporary mainstream political rhetoric has swung sharply in the right’s favour. In Birmingham, once more tensions are rising amid national economic stagnation — Nigel Farage’s hard-right Reform Party is looking to this year’s local elections to make inroads and see the region as a significant target for the party.

But before Reform’s right-wing populism took hold, the BNP enjoyed a final surge in popularity in the West Midlands, at the start of this millennium. That rise — and fall — is the subject of next week’s essay.

Next Saturday, our third and final essay on Birmingham and British fascism focuses on BNP deputy leader Simon Darby and the party’s shift to Islamophobia.

In 2026, you don't need clickbait or 'churnalism' clogging up your inbox. Out with advertorials, listicles and opinion articles masquerading as analysis. The Dispatch is committed to the kind of rigorous and informative journalism Birmingham needs during this election year. To do that, we rely on support from readers like you.

It's just £2 a week for all three weekly editions. Get investigations, news briefings, culture rundowns and deep dives into Birmingham's history - just like this essay series - straight to your inbox. Plus, we'll give you discounts to our exclusive events.

We are a reader-funded publication, doing old-school journalism using shoe leather and a nose for news. No annoying pop-up ads or stories about what Kate Garraway wore on ITV this morning. If that sounds appealing, click below to support us.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments