At a sodden Spaghetti Junction, a Mini Clubman descends from the M6 to the Aston Expressway. These roads have been open barely a year, but already look much older. Visible in the background are the grime-blackened cooling towers of Nechells Power Station, standing roughly where Star City does today, and, next to the Expressway, rows of factory rooftops. The 20-year-old tower-blocks of the Holte & Priory Estate also interrupt the skyline. Austin Maxis and Triumph Dolomites trundle past. A van has broken down in the far lane.

We cut to inside the car. A familiar man wearing a brown three-piece suit and matching tie is at the wheel, his expression grim. His inner monologue begins to play out as the car putters into town: “Just as bad as I expected… Even worse. But I’ve got to face it — face Birmingham!”

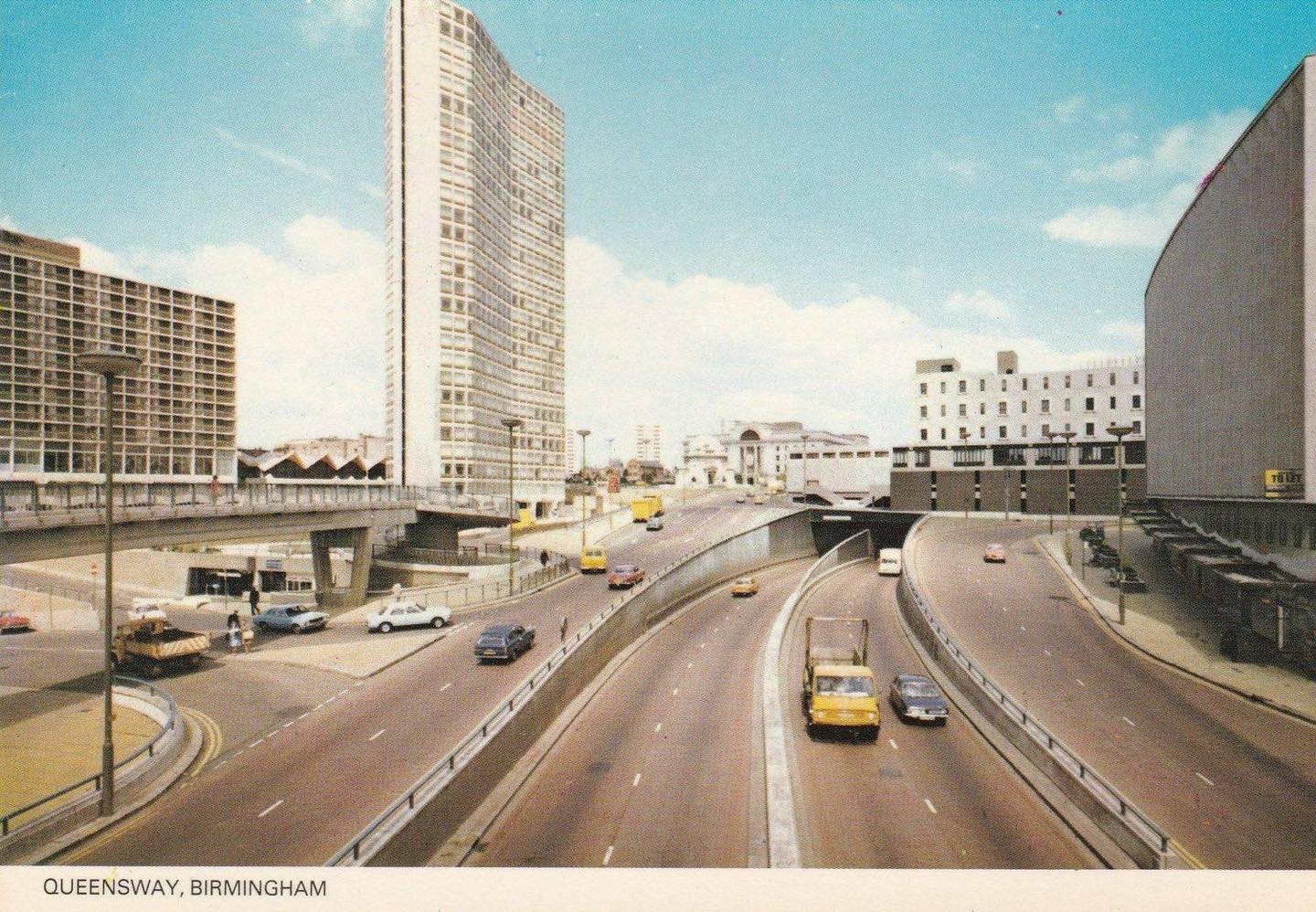

This is 15 minutes into Take Me High, a 1973 musical comedy, starring Cliff Richard as Tim Matthews, an ambitious banker reluctantly sent to Birmingham. It’s a truly bizarre use of celluloid, but also a fascinating document of the city’s unforgiving post-war redevelopment, as directed by infamous architect Herbert Manzoni.

I only learned of Take Me High’s existence two years ago, during my ongoing research into local musical history. Picking up a copy from eBay, I stuck it on and was mesmerised. Not by the threadbare story or forgettable songs (I’ve played the title track three times today and still couldn’t hum it to you), but with the Manzoni-fied Birmingham it captures in glorious technicolour.

But Take Me High gets just four sentences in Cliff’s 2020 autobiography The Dreamer, his opinion of it simply: “It was an interesting film”. This concise assessment could potentially be because the project ended his run on the silver screen for good.

See, when Cliff Richard found fame in 1958, he was hailed as the English Elvis, thanks largely to ‘Move It’, the first genuine British rock’n’roll record. But 15 years later, he was treading musical water. His priorities had shifted, and with them, the nature of his fame. He may have finished third in that year’s Eurovision with the bombastic ‘Power to All Our Friends’, but, as he admits in The Dreamer, the public now recognised him as: “1) a Christian, 2) a TV entertainer, and 3) a pop singer”, in that order.

Why he, or anyone else, believed the remedy was a Birmingham-based musical comedy about boats and burgers is unclear. Maybe that’s how people thought in the early 1970s. Take Me High was filmed in June under the working title Hot Property (which better fits the storyline but maybe sounded a little too ‘bow chicka wow wow’ for its star’s fanbase), on a budget equivalent to £3.3 million today.

Cliff had, of course, been in films before, most notably 1963’s Summer Holiday. His last big-screen outing, 1967’s Two a Penny, hadn’t proved successful. By 1973, it was being screened in churches rather than cinemas, which tells you all you need to know.

Take Me High is surrealist in nature, if not in intent, featuring sequences of TV sets being machine-gunned and Cliff inexplicably zooming beneath Spaghetti Junction on a mini-hovercraft. What connection they have with the storyline – where London-based Tim is inexplicably transferred to Birmingham, instead of New York — is unclear.

Never mind though; once Tim has navigated the ring road, he’s thrust into the thick of things, meeting locals including love interest Sarah (played by Deborah Watling, best known for her Doctor Who sidekick stint), socialist councillor Bert Jackson (George ‘Arthur Daly’ Cole) and his capitalist nemesis Hugh Cunningham (excellently hammed-up by Hugh Griffiths). He then decides to move to the dead-centre of the city. According to his map, that’s Gas Street.

His walk there is the film’s highlight: three-and-a-half minutes of flared-suited striding around the city centre to a song called ‘Winning’ (“I believe that you’re a tough town, and that’s the way I like ‘em!”). It’s the one moment where it’s hard to tell if Cliff or Brum, the new, 1970s Brum, is the star.

That’s what makes Take Me High increasingly valuable as the years pass: the background, not the action. Whereas the Brummie crowds in the film are visibly going, “Wow! Cliff Richard!” (or in some cases, “the bloody ‘ell’s this, then?”), today’s viewers are going, “Wow! The Bull Ring! The old library!” Everyone has their favourite bit. For local artist Tom Hicks, who recently screened the film at The Mockingbird, it’s the Ringway Centre; for Dean Kelland, who co-hosted the showing with Hicks, it’s Alpha Tower. For me, it’s the long shot of Tim bowling across a pre-pagoda, Pagoda Island. “It takes me back to the Birmingham I grew up in,” Kelland tells me. “I was born the year the film was released, [and] the Brutalist backdrop within it is wonderful.”

Much of the film features boats and canals. We finally reach Gas Street Basin, which, in 1973, was still run down from its Victorian heyday. There we meet Sarah’s parents, also acting like characters from a bygone era — and tellingly they provide Take Me High's only Brummie-accents. Then we’re out into the Warwickshire countryside on Tim’s pimped-up narrowboat, where he and Sarah get an idea for a burger business — ‘Brumburger’ — before kissing (modestly — this is a Cliff Richard film, remember).

Back in town, the new couple thrash their Brumburger recipe out during a dire duet stylistically different from every other song in the film (the burgers are also burnt by the time they’ve finished). Tim gets the socialist and capitalist characters to shake hands on a deal for the never-explained ‘City Cross’ scheme and back his and Sarah’s new restaurant. He’s got the girl, bridged ideological divides, and brought gourmet burgers to Brum. What a guy.

We then cut to what, prior to rewatching, I remembered as the final scene: a huge ticker-tape parade up Corporation Street with marching bands, majorettes, motorbikes, and more. It’s not actually the end — there’s still the obligatory everyone-dancing-while-Cliff-sings-in-the-new-burger-restaurant climax — but it’s where the force of Cliff’s sheer Cliff-ness dissolves what’s left of the façade and reminds us why we’re here (to revive his flagging career).

Take Me High’s Birmingham premiere was at the ABC Cinema on Bristol Road, where McDonald’s is now, on 19 December 1973. The PR machine was whirring away, with a making-of programme called When the Cameras Came to Brum. This accompanying show aired on BBC 1 and Cliff appeared on Pebble Mill to gush about how filming had changed his view of the Midlands. But the national reviews were as frosty as the weather.

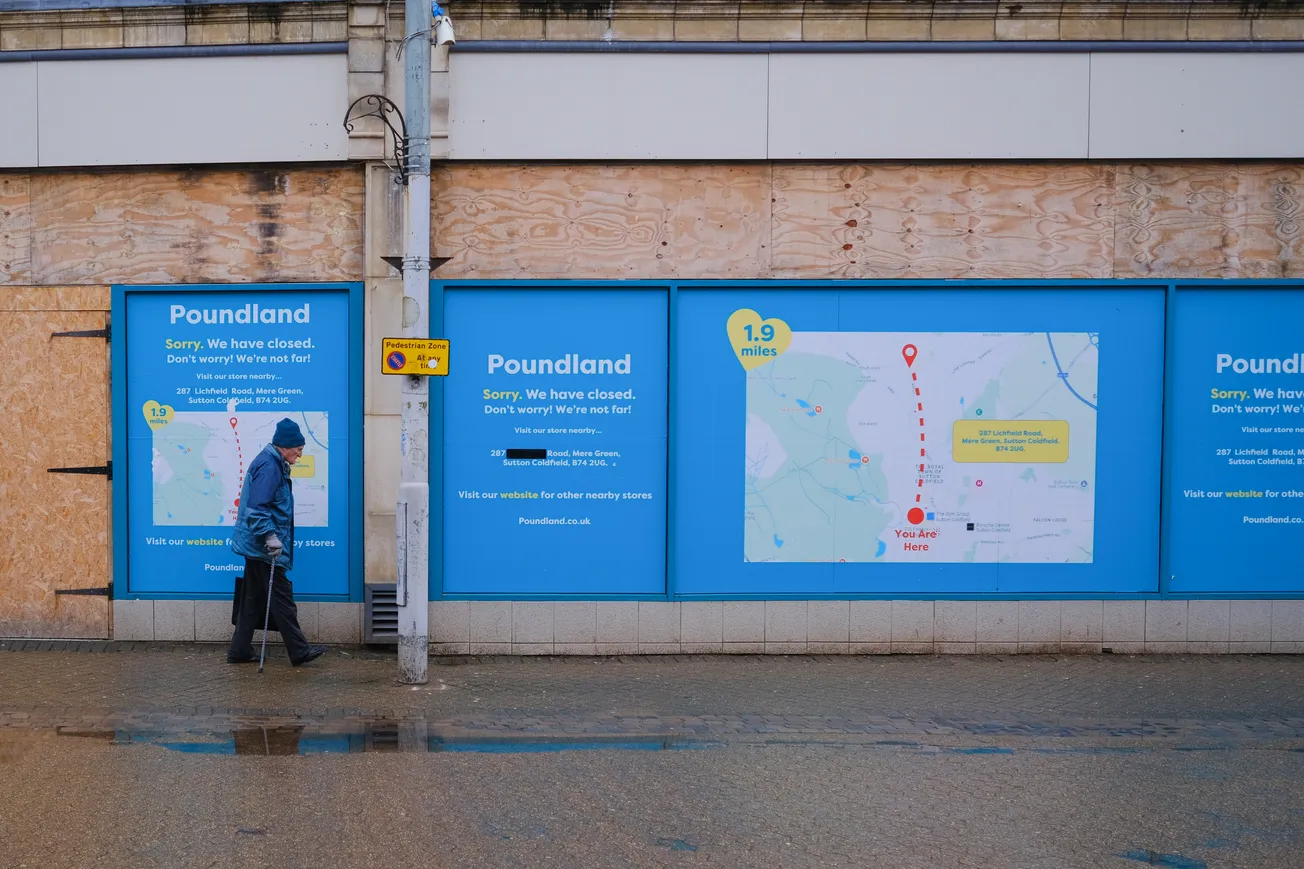

The Guardian likened it to “a large basinful of pink blancmange”, while the Daily Mirror said, “it does nothing [for Birmingham] — and even less for Cliff Richard.” Indeed, it was the final nail in the coffin containing his film career and drove his musical one further down a dead-end: the soundtrack album sold poorly and his next album failed to chart. It would have finished an artist less used to ridicule, but this was Cliff Richard. Come 1976, he was back in the top ten with ‘Devil Woman’.

Local reviews of Take Me High were equally scathing, labelling it “naïve and feeble” and “all flailing arms and soft punches”. The Birmingham Post took issue with the implication that Brummies were “provincial, excited by parades, and undiscriminating about food.”

But if there’s one thing the local press did like about the film, it’s how good Brum looked — “an impression…a tourist board could hardly equal,” cooed the Evening Mail.

Whether that’s true or not becomes increasingly subjective with time. And regardless of if the film intended to praise the city or use it as a punchline, Take Me High’s unexpected legacy is to act as a kind of Brummie Rorschach test: what do you see in its depiction of the angular ‘new’ Birmingham of 1973? An ugly, car-worshipping mess that, like Cliff’s career, needed desperate reinvention? An ambitious feat of post-war planning? Or a nostalgic vision of your childhood? It’s a question that becomes more poignant with each landmark razed and every area redeveloped beyond recognition.

As the credits roll, after a long 86 minutes, the camera pans slowly across an overcast city centre skyline. As an older millennial, it’s a form of the city I only vaguely remember, but like the Cliff hits of my childhood, ‘Mistletoe & Wine’ and ‘Saviour’s Day’, I admit I’ve got a soft spot for it because it’s comforting — somewhere in that vast concrete sprawl are my family members, many of them long-since departed, going about their 1970s lives. Maybe yours are too.

So, if there’s ever another screening or you spot the DVD in a charity shop, don’t look back or turn away because, as Tom Hicks concludes, “it’s off-kilter, but there are some great bits in it. It fits Brum well.”

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments