Want to work for Britain’s most exciting new media company? The Dispatch is looking for a new staff writer to join Samuel and Kate in leading a renaissance in high quality local journalism in Birmingham. This is a job for a journalist who believes in our mission, loves the kind of reporting we do and is passionate about applying our brand of journalism to many more stories in the years ahead.

We need someone who has a natural flair for writing — who will deliver the kind of stories our readers look forward to when they open our newsletters. If you fit the bill, or know someone who does, please click the button below to find out more.

I kick things off with a softball question. What is Richard Parker’s favourite restaurant in Birmingham? I’m thinking he’ll be a Piccolino man, but perhaps he’ll surprise me by saying he enjoys an upmarket tikka masala at Asha’s.

I do not expect him to reply: “the one where the meal finishes as quickly as possible.”

Evidently, it’s not much fun being mayor of the West Midlands. It’s been 16 months — a third of Parker’s term — and the novelty seems to have worn off.

When he and I last spoke at length, it was just 110 days after his election. The jury was still out on what kind of leader he would be. Early reports suggested the former accountant was still in campaign mode: too focused on criticising his Conservative predecessor, not enough energy devoted to making his own mark. Perceptions of a lacklustre start weren’t helped by the West Midlands Combined Authority insiders who told The Dispatch that Parker had been slow to get going, taking a while to even appoint a team.

“Richard’s early days,” said one Labour source at the time, “have been marked [...] by disinterest”.

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

What’s more, part of Parker’s pitch for the job had been his close relationship to the national Labour party leadership, particularly his friend, UK chancellor Rachel Reeves. It was a clear departure from the more independent approach taken by the former mayor, Andy Street, and his Greater Manchester counterpart, Andy Burnham. The question was: could Parker put the West Midlands before his loyalty to Labour HQ?

Today, Parker still defends being a party man, maintaining that the region must work with the government, not against it.

That’s the approach he’s taking with the biggest challenge he faces, and the one I intend to discuss over coffee: reviving the region’s economy. Unfortunately, thanks to scheduling issues, we have to settle for a video call. He logs in late, slightly frustrated due to a bit of tech trouble, but ready to chat growth — or lack of it.

To that end, Parker recently unveiled the West Midlands local growth plan, a blueprint closely aligned with national government’s new, ten year industrial strategy.

Research began 18 months ago but the finished product has undeniably been shaped by his leadership. The plan promises to bring 93,000 more people into work by 2035 and to increase productivity, adding £17.4bn to the West Midlands’economy. This will largely be achieved by ‘upskilling’ the region’s existing workforce, and attracting new businesses and well-paid jobs. Key sectors include: tech, the creative industries, financial services, advanced manufacturing, and green energy.

Crucially, according to the plan, these won’t only be concentrated in Birmingham but in three key spots across the region: Birmingham and Solihull, Coventry, and the Black Country. Together, they cover the entire WMCA conurbation.

It’s a ‘polycentric’ approach that was recently criticised by the economist Paul Swinney in a blog post for the thinktank Centre for Cities. In it, he writes that the West Midlands would do better to mimic ‘monocentric’ Greater Manchester. Focus on one spot, Swinney argues, the place where most of the jobs currently are: Birmingham city centre. Keep growing the number of jobs here, Swinney says, and the benefits will trickle outwards to the rest of the region.

The WMCA’s chief executive, Ed Cox, has published his own rebuttal on LinkedIn, but Parker is more forthright: “Frankly, it’s neoliberal nonsense,” he says. This surprises me, so I try to get him to define his own political outlook, but he resists. “Sorry, I don't follow a political philosophy. I follow a realism and a pragmatism about what we need to do to get really, really good jobs here and make sure everyone benefits.” He suggests if this has a name, it’s “Parkerism”.

Pleased, he continues: “If you follow the Centre for Cities thesis, every job will be in financial services or in tech, and everyone will be getting a job within the inner ring road of Birmingham.”

Lots of businesses want to invest in other parts of the region, Parker adds, and moreover, this spread is essential to ensure a fair distribution of wealth. This even-handedness could be why the growth plan has been signed off by all seven of the WMCA’s member authorities. It’s an equilibrium which is historically uncommon — the different councils do not always get along.

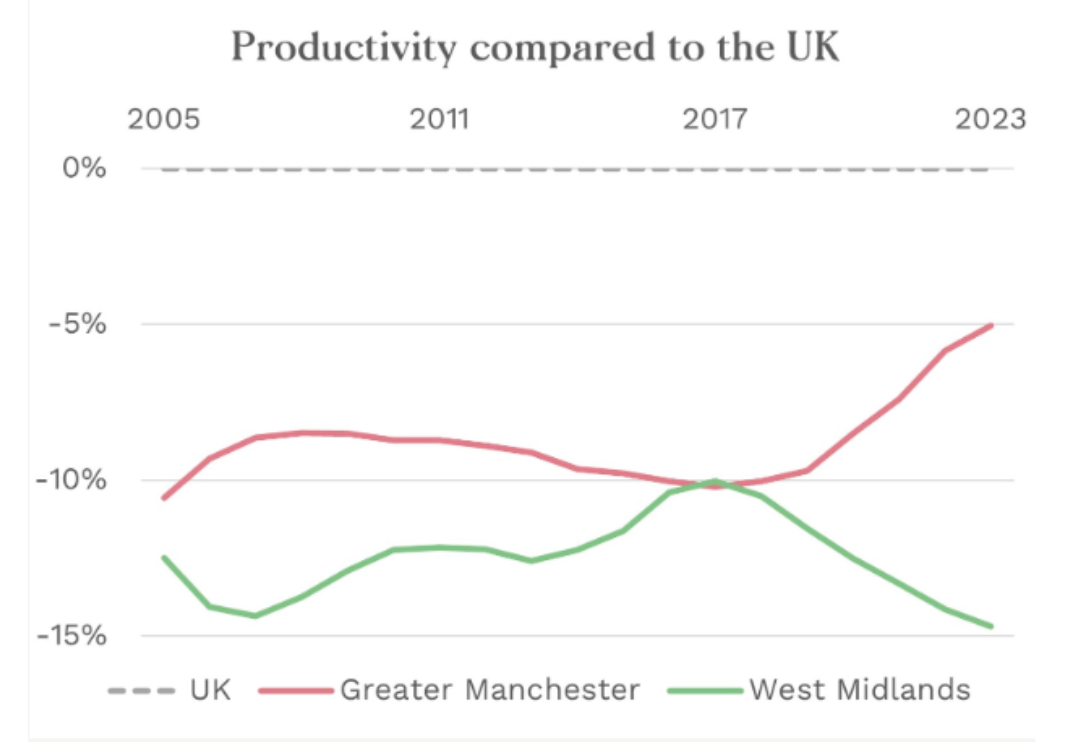

But there is no better time to come together. As The Dispatch revealed in a July article, things are looking bleak for the West Midlands. Over the past decade, our economy has faltered; by contrast, Greater Manchester has enjoyed growing prosperity. In particular, productivity in the north west has vastly improved, leading to higher wages and an overall, better quality of life. While the rate of productivity in Greater Manchester is now approaching the national average, ours has dipped in the opposite direction.

“We're still understanding exactly why that's the case,” says Parker (The Dispatch identified Greater Manchester’s far superior transport network, that allows people to quickly travel into the city centre for work, as a key factor).

“But there is no doubt that Manchester as a city region has benefited from more investment and [attracted more] jobs that are more technology driven.” That, he explains, warming to his theme, is also a function and a reflection of its history. “It didn't suffer quite as much from de-industrialisation as we did,” he claims. “It had lots of manufacturing, but not as much heavy industry.”

Moreover, he says the political leadership up north has been very focused on providing training so that people here have the skills that incoming companies need. “We’ve been terribly poor at that in this region,” he adds, hence the focus on skills which align with national government priorities.

These include growing the defence sector. UK PM Keir Starmer has committed to a 5% increase to the defence budget by 2035 to better align us with NATO targets and spending by other member states. This “presents major opportunities” for the West Midlands, according to the growth plan, because local engineering and manufacturing firms can benefit from new contracts and universities can “support innovation in defence technologies”.

The West Midlands isn’t currently a hub for defence manufacturing. But with more government money earmarked for it, it’s not surprising that the authority wants to maximise the chance of getting a share by advertising our existing, adaptable infrastructure. However, that comes with risks, especially amid national controversy over the sale of British weapons to Israel.

When I ask Parker if he is concerned that the potential increase in weapons manufacturing will put people off, he says it’s simply a matter of creating jobs. “What we want to create here is fundamentally about winning contracts with government,” he shrugs, adding that I am focusing on a small part of the sector that is more sensitive, whereas many of the jobs will be creating “secure vehicles” and supporting British naval fleets. “The people I speak to who are employed in those businesses and their families are very keen that I support them as much as possible.”

Does he think the growth plan makes it clear to residents that these jobs might contribute to warfare? “No,” he confirms. “They're supporting the security of the country. It's very, very, very different. It's not supporting warfare. It's supporting the defence and security of the UK.”

But when I ask him if he is certain that none of the jobs will involve creating commercial weapons that will be used by other countries he says “I can't rule out that explicitly, the UK government would decide, ultimately.”

These questions are pressing ones. Richard Parker won his 2024 mayoral election by a very slim majority of 1,508 votes. Support for Labour was diminished in many majority Muslim areas, partly because of the strong opposition to the party’s stance on Israel’s onslaught on Gaza. Parker, in his early interviews as mayor elect, committed to winning them back round. “I understand how important this issue is to them,” he told the BBC at the time.

Today, he refuses to be drawn on whether he thinks Israel is committing genocide (our conversation takes place the day after world leading experts on genocide declare it is, and a week before the UK government determines it isn’t). I also want to know if Parker would be able to call it a genocide without pushback from Labour HQ.

“I haven’t even asked them. I haven’t made any comment and I don’t intend to,” he tells me, firmly. Line of inquiry closed, I sense.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can get in touch at grace@millmediaco.uk or visit our advertising page below for more information

Such briskness simmers beneath the surface throughout our discussion. Parker is friendly enough, and sources who have worked with him say he is easy to get along with. Nevertheless, he seems more impatient now than he did last year. When I ask him if he is bored of the press comparing him to Street, he responds, "you can report what you like, I've just come here and got on with the job". I start to wonder if he wanted to have our interview on Teams because he is simply tired of having to see people. He reveals he recently had to go out wining and dining for 21 nights in a row.

But I have queries that need answers, so I persevere. What will Parker be asking of Downing Street? Does he plan to take on all the powers that have been made available to him? One in particular that stands out is the authority to create ‘mayoral development corporations’ (MDCs) — public bodies that oversee regeneration schemes.

MDCs can construct buildings and infrastructure, and can be granted powers to take over planning duties from local councils. They can make compulsory purchases (e.g. force the sale of privately-owned buildings left to rot) and grant local businesses relief from standard rates, helping small, independent entrepreneurs get a foothold. Andy Burnham set one up in Stockport in 2019 and recently announced a new MDC for a major sports-led scheme in Old Trafford.

The West Midlands doesn’t yet have one, despite the fact, as Parker says, “it takes too long to get stuff done,” especially on transport projects like metro extensions. Could an MDC be in East Birmingham’s future, to hasten the Knighthead-led Sports Quarter?

“I'm looking at all the flexibilities and powers we can have, working with our partners here that will speed up delivery,” he adds. “MDC’s are a very effective way of doing that and we are making good progress in those conversations.”

In the meantime, we can expect updates on transport improvements soon. With three big schemes ongoing — the East Brum metro extension, several new train stations under construction, and buses coming under public control —- Parker has brought in a helping hand. The economist Bridget Rosewell, a former advisor to the Greater London Authority, is currently identifying which new projects to prioritise, so they can best link up with the work that’s already underway. She will report back later this autumn.

For now though, my time is up. Parker has another meeting to get to in five minutes. Closing my laptop, I’m left with a clear enough picture of his plans for the region, but a less vivid image of the man himself. My strongest impression is that he mostly wants to be left to get on with the job at hand. He doesn’t want to be distracted by inconvenient questions. Or even worse – frivolous dinners.

Comments