Want to work for Britain’s most exciting new media company? The Dispatch is looking for a new staff writer to join Samuel and Kate in leading a renaissance in high quality local journalism in Birmingham. This is a job for a journalist who believes in our mission, loves the kind of reporting we do and is passionate about applying our brand of journalism to many more stories in the years ahead.

We need someone who has a natural flair for writing — who will deliver the kind of stories our readers look forward to when they open our newsletters. If you fit the bill, or know someone who does, please click the button below to find out more.

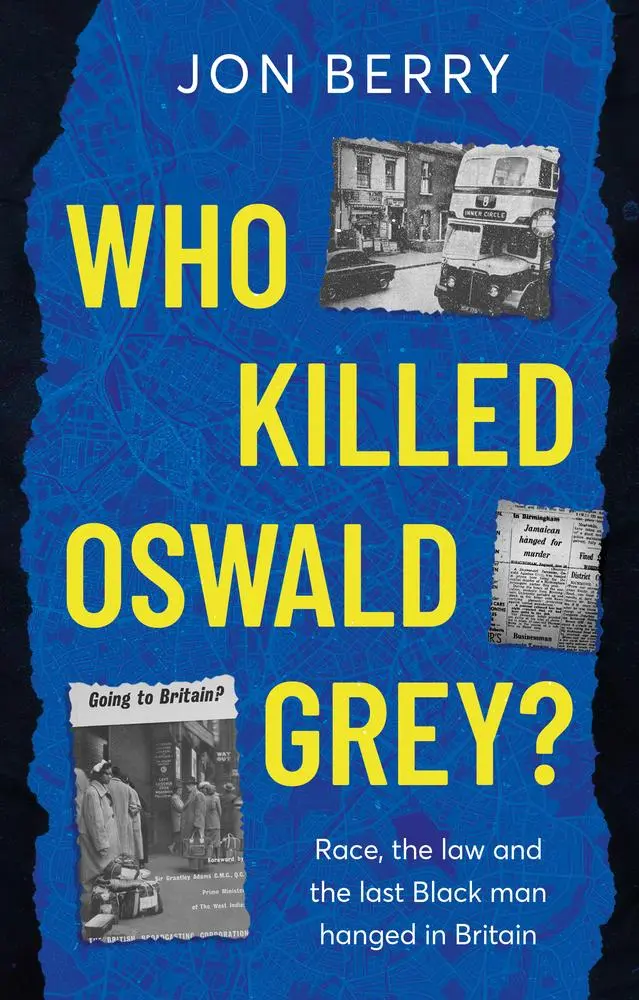

In the autumn of 1960, 18-year-old Oswald Augustus Grey set out from his home in Bog Walk, Jamaica for the last time. He had been summoned by his father, Felix, to join him in Lozells, Birmingham, where he’d been living for some five years.

Oswald was the oldest of seven siblings. But it was not just his seniority that prompted Felix to call him to the “mother country”. Even as a boy, he had courted trouble. An infrequent attender at Tulloch Primary School, he had drifted into a life of petty misdemeanours; a fetcher and carrier for unscrupulous small-town villains.

His teenage years were lost in reform schools that had little to do with rehabilitation and plenty to do with learning the craft of the criminal. Felix hoped that by bringing his first-born to Birmingham, he could keep him near and straighten him out.

Within weeks that hope had been extinguished. Unable and unwilling to hold down any sort of job, Oswald found a way of shocking his already disappointed father. Desperate for money, he broke into the electricity meter in the house where they lived on Gordon Road and stole the few coins in it.

For Felix, this was the last straw. In a desperate attempt to teach his wayward son a lesson, he took himself to Ladywood police station to report the crime. The outcome was disastrous. At a time of moral panic about youth crime – not to mention widespread suspicion about conspicuous outsiders from the Caribbean – the law was unforgiving of Oswald Grey. He was sentenced to six months’ detention.

With no custom-built facilities for youth custody, he was to serve his time in Winson Green prison. And so his education in the ways of felons and his acquaintance with a circle of like-minded individuals received an unfortunate boost.

On his release, living with the father who had handed him over to the law was no longer tenable. He found lodgings in Cannon Hill Road – and, in due course, moved into the circle of Harris Charles Carniff, known universally by his street-name, Mover. In the decade or so since his arrival from Jamaica in 1950, Carniff’s mischief and thievery had already seen him serve three terms at Her Majesty’s pleasure. His dealings with the boy from Bog Walk would have fatal consequences.

When it comes to what happened in the weeks after Oswald and Carniff met, there are some things we know and some things we do not. Let’s start with what is known.

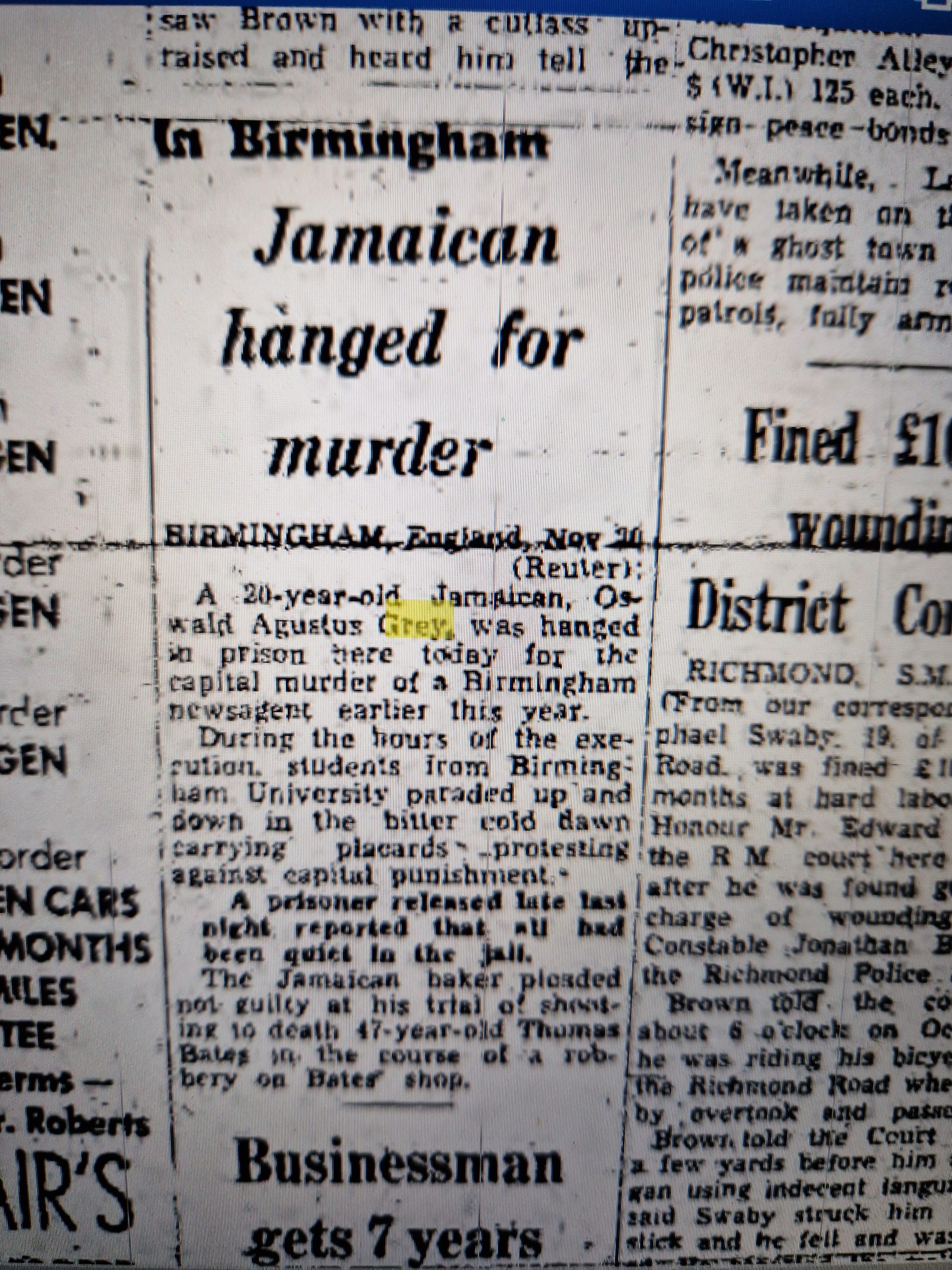

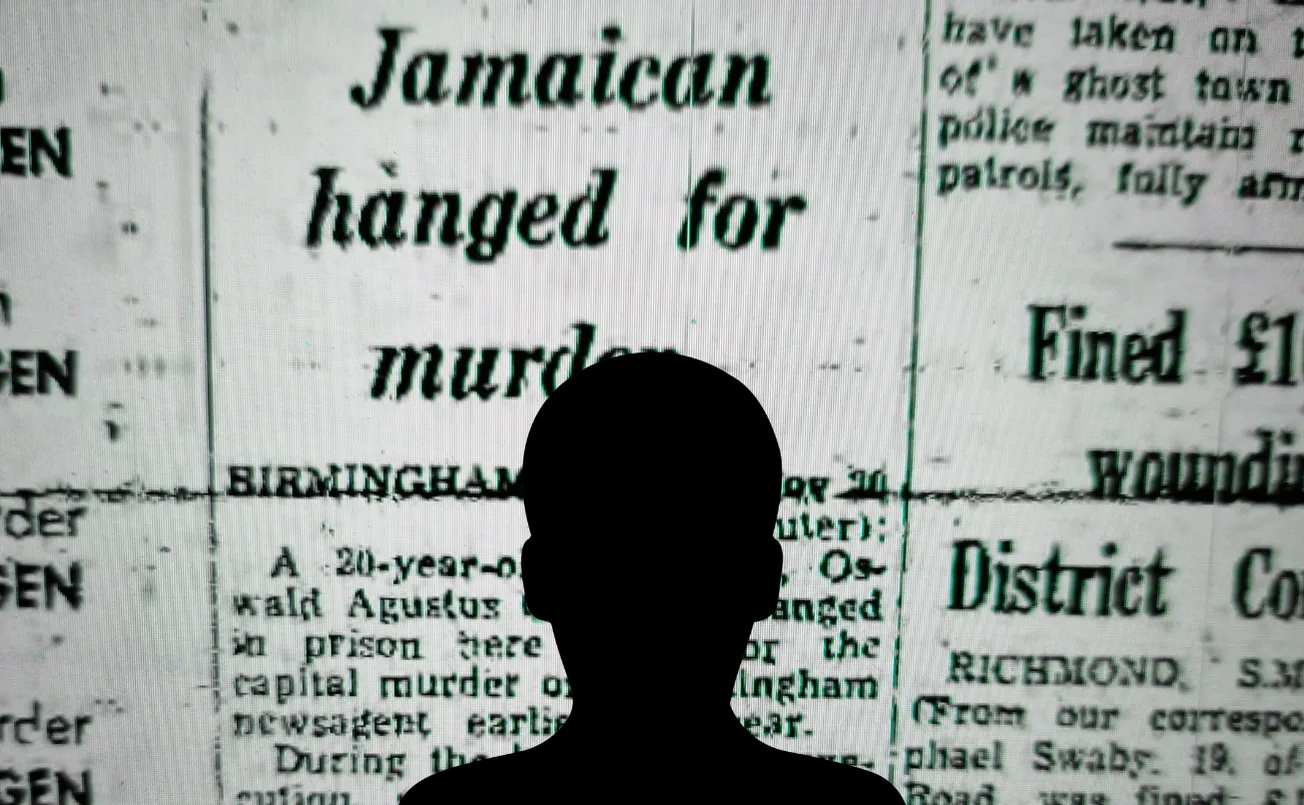

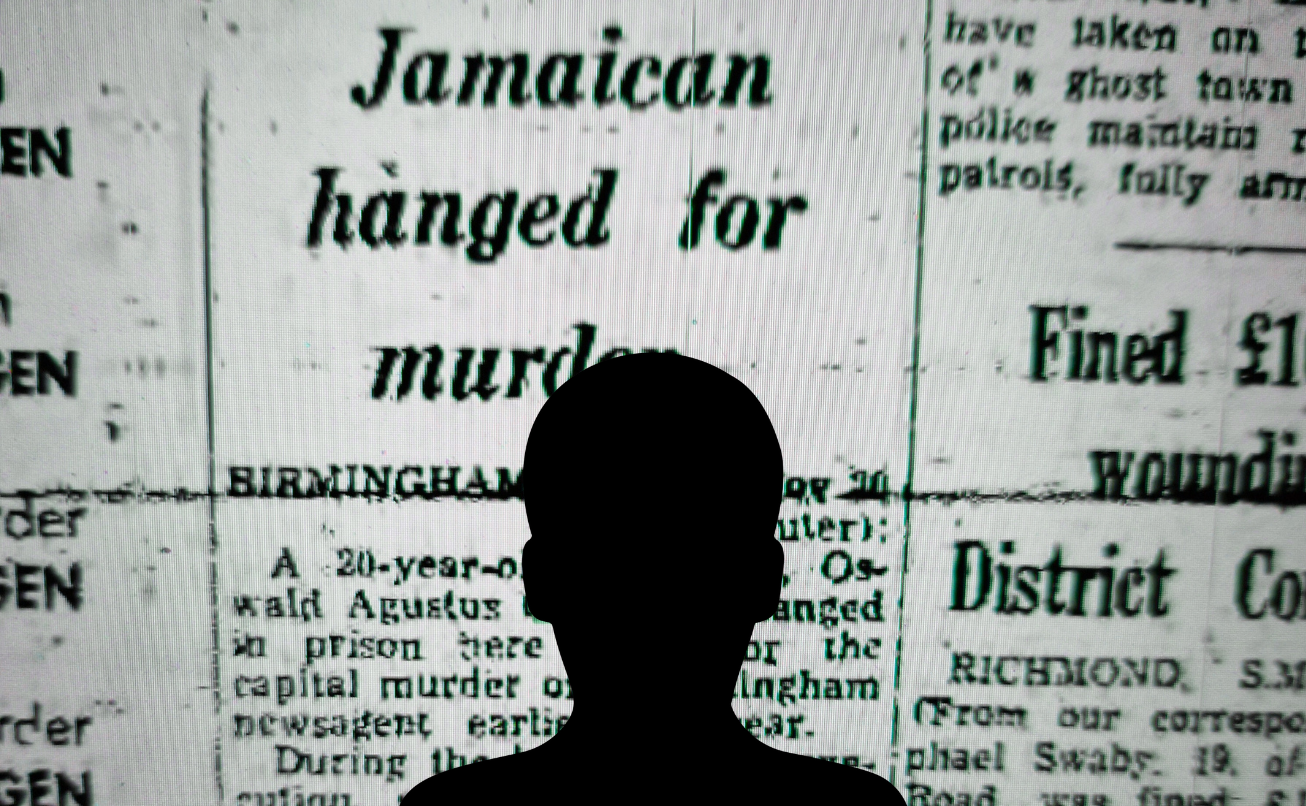

At 6.30 p.m. on Saturday 2 June in Lee Bank Road, 47-year-old newsagent, Thomas Bates, was killed in his shop by a single bullet from a Walther automatic pistol. On Wednesday 6 June, Oswald was arrested and charged with stealing a pistol – from a Mr Hamilton Bacchus in Varna Road – which he admitted. He was remanded in custody until 5 July and charged with capital murder. His trial began on the morning of Monday 8 October and he was convicted and sentenced to death by lunchtime the following Friday. His appeal took place three weeks later and was over in less than an hour. On Friday 16 November, the Home Secretary declined any chance of a reprieve and the following Tuesday – 20 November – Oswald Grey was led to his death in Winson Green prison by hangman Harry Allen.

From the death of gentle, well-respected shopkeeper, Thomas Bates, to the execution of Oswald Grey, six months did not pass. He was the last man to be hanged in Winson Green and the last Black man to be hanged in Britain. Only five more men went to the gallows before the abolition of capital punishment in 1965.

This much we definitely know. But much has gone unanswered. And the most important question remains: was it a secure conviction?

The prosecution case was led by Graham Swanwick and the presiding judge was Gilbert Paull, who was known to be a great interrupter. Transcripts of the trial that survive – something we’ll come to later – reveal his impatience. Oswald’s own testimony probably prompted some of this. From the moment he was first arrested he changed his stories about his movements and, most importantly, his possession of the gun, on four occasions. He had trouble making himself understood, constantly being asked to repeat himself; his speech, of course, was still that of a young man from a relative backwater, unfamiliar to the ears of the Oxbridge men who orchestrated court proceedings.

Why did Oswald change his story so often? First, there was little doubt that he was in thrall to Carniff, who he possibly wanted to protect. Second, there seems little doubt that from the moment of his arrest, he was badly treated and coerced by police officers. His defence counsel, Arthur James, referred to his being kicked and spat at by them, but could say nothing stronger in his statements than that this was “very wrong”. He made no claim that this could cast doubt on any potential conviction.

The prosecution was unable to prove with absolute certainty – and remember that this was a capital case – that Oswald was in possession of the murder weapon at the time of the shooting. Neither Swanwick nor Paull could incontrovertibly attest to the jury that he had it on the evening in question.

The two key witnesses for the prosecution were local woman, Cecilia Gibbs, and Carniff. Gibbs was a known police informer and had occasionally received financial reward for her snippets of information. She had picked out Oswald in an identity parade but was only one of four people in 25 to do so. Carniff’s dabbling in minor wrongdoing was to occupy the constabulary on and off for a further three decades. Judge Paull identified him as “a man of bad character”. When Carniff testified against Oswald at the trial, he had his own back to watch.

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Most important of all was the letter of the law. The Homicide Act of 1957 stipulated that murder in pursuit of theft had to be punishable by death. Yet there was no proof that anything had been taken from the shop of Thomas Bates. The till remained closed, the petty cash box unemptied.

Most significantly, the Act was unequivocal that anyone suffering from, in the uncomfortable terminology of the day, “arrested or retarded development of mind” could not be subject to this most draconian of sentences. Throughout the trial and in accompanying documentation, there is frequent reference to Oswald’s “low mentality” and “poor intelligence”. It was recognised that he was barely literate and that, in the words of the prosecuting counsel, he could be persuaded to “turn like a weathercock from one position to another”. This mitigation, central to the Act, was ignored in the haste and impatience which characterised his treatment.

Even after his failed appeal, there was one further throw of the dice. Henry Brooke was Home Secretary at the time, and it was within his power to commute the death sentence to imprisonment. Such mercy was not unknown. One case in four ended with such a reprieve and these were usually instances of young men who had acted stupidly and impetuously. But there was nothing about Brooke to suggest that he might be open to exercising such clemency.

He had assumed office in July 1962, weeks after the murder of Thomas Bates. One of the first pieces of business to cross his desk was to confirm the deportation of a young Jamaican woman, Carmen Bryan, who had been convicted of shoplifting goods to the value of £2. Despite strong opposition from both sides of the House of Commons, Brooke ratified this sentence.

His stubbornness did not last long. Having been persuaded that deportation was too severe an outcome, he relented – but with no great grace. Brooke told the House that although he was inclined to be lenient on this occasion, he warned “that if people want to return to their own country, they had better not imagine that the better way is to go stealing in shops and rely on that to get home at the taxpayers’ expense”.

The fate of Jamaican, Oswald Augustus Grey, was in the hands of this man. No wonder, then, that he appeared to have little compunction in signing the death warrant in his neat hand – “the law must take its course”– four days before the hangman went about his business.

Most – not all – papers relating to the arrest and trial of Oswald Grey are unavailable for inspection. They are withheld from public view and will not be obtainable until 2062, one hundred years since the events in question. I have spent more time contesting this decision using Freedom of Information (FOI) requests than I care to consider. The decision remains unchanged: to protect the mental health and wellbeing of surviving relatives of both victim and defendant, this material remains under wraps.

This is unconvincing. TV schedules are filled with dramas and documentaries, many of which relate to crimes in recent living memory – and plenty of which explicitly acknowledge that material has been taken from official documentation. Are the sensibilities of those connected to these crimes not to be considered?

There is another weakness in this argument. The execution of Oswald Grey is almost forgotten history. In five years of research, it’s not been possible to locate more than a handful of people who have any reliable recollection of it. Far from being offended, the most common reaction from those to whom I have spoken has been to thank me for my efforts in revealing the story. Concerns about the mental health of unidentified individuals seems, to use the FOI Commissioner’s own words about the ruling, “on the cautious side”.

So how to explain this official secrecy?

Among the concealed trial papers is the medical report on Oswald Grey. We’ve already heard that his trial took place at a time when even the language of officialdom sounds crude and demeaning to modern ears. During proceedings, prosecuting counsel Graham Swanwick referred to those newly arrived in the city as living “a strange fluctuating life rather near the underworld.” On asking about the defendant’s brown coat, the question was asked “whether it was [N-word] brown”. It is clear throughout that those who had arrived from Jamaica were second-class citizens who, in Swanwick’s words, “led aimless lives”.

It is too easy to imagine the language and content of a report written in 1962 by a prison doctor frustrated by an inarticulate, half-literate Jamaican – a young man confused and, quite possibly, battered, whose very presence irritated and infuriated his captors.

And it is just as easy to imagine the reluctance of those who hold this report to allow it into the public domain – not least because the initial request to see it came just as the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis sparked the global Black Lives Matter movement.

The story of Oswald Augustus Grey, treated as disposable and the victim of hasty justice, echoes to us from over 60 years ago. And there remains one more injustice that should – and can – be addressed.

November 2025 marks 60 years since the abolition of capital punishment in the UK. When that law was changed, it also amended one of the cruellest facets of execution. Until that point, those who had met their death on the gallows suffered one further indignity. Their remains were to be kept within the prison walls – their loved ones were not afforded funeral rites.

Although the 1965 legislation overturned this centuries-old practice, there was no obligation on the part of prison authorities to inform families of this new provision. Oswald Augustus Grey remains buried in plot 27 on the grounds of what is now HMP Birmingham.

There could be no better way of bringing this telling and tragic piece of forgotten Birmingham history to light than by affording this bewildered and abused young man a more fitting resting place.

Comments