Early on Saturday 30 September 1967, the BBC launched Radio One, designed to replace the offshore pirate stations shut down by Harold Wilson’s Labour government. After a couple of introductory jingles, Tony Blackburn played its first chart single, “Flowers in the Rain”, by five working-class kids from Birmingham.

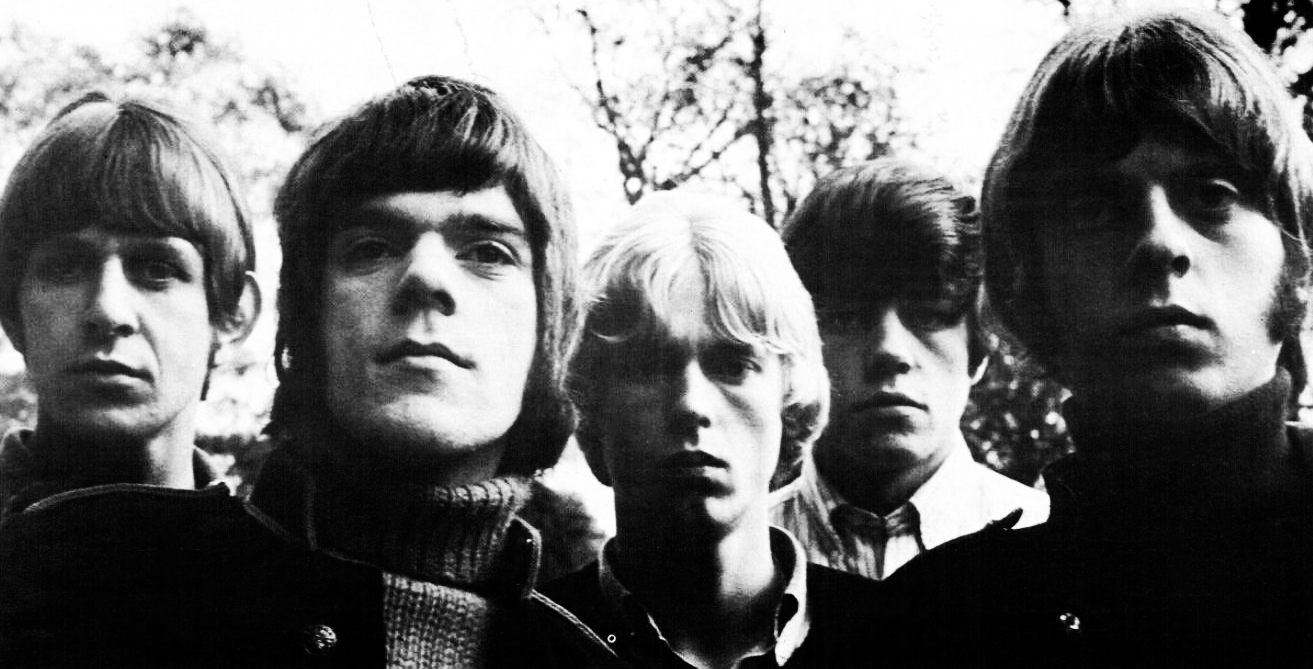

Barely a year old, The Move had already gained a reputation as one of the most exciting bands in the country, combining a proto-punk energy with perfect pop songs and finely crafted vocal harmonies.

They had a residency at London’s Marquee, their first two singles had been big hits, and they had been praised by The Beatles. Manager Tony Secunda would later claim that between 1966 and 1968, “without a doubt, it was The Beatles, the Stones and The Move, in England… in that order.” It was an exaggeration, but not a ridiculous one.

But within a month of Radio One’s launch, they had been successfully sued for libel by then prime minister Harold Wilson in a high-profile court case. It was the start of the downfall of a band who, had history been less unkind, would now be mentioned in the same breath as The Who or The Kinks.

A remarkable, chaotic experience

In the early 60s, Birmingham was full of bands playing versions of classic soul and rock ‘n’ roll tunes, at a dizzying range of venues. The scene’s centre was the Cedar Club on Constitution Hill, run by Eddie Fewtrell, who famously faced down the Krays when they attempted to move into Birmingham. It was also a meeting point for local musicians; after closing time they would chat at Alex’s Pie Stand outside.

This vibrancy led Decca Records to try to market ‘Brum Beat’ as a rival to ‘Mersey Beat’. A handful of bands had limited success – such as the Rockin’ Berries, who in an early incarnation featured Christine McVie of Fleetwood Mac, and The Applejacks, notable for Megan Davies, probably the first female guitar or bass player in a beat group.

There was one genuine breakthrough: The Moody Blues, whose “Go Now” became number one in late 1964. This showed that Brummie bands could make it big, particularly when the feat was repeated by Steve Winwood’s Spencer Davis Group the following year.

Some local musicians, aware that the city was now thought of as having a happening scene, were growing restless. Chris “Ace” Kefford, then bassist with Carl Wayne and the Vikings went to the Cedar one night with fellow member Trevor Burton, to see a mod band from London — Davy Jones and the Lower Third.

Their lead singer would shortly after adopt the name David Bowie, but not before suggesting to the pair that they should form a new group with the city’s best musicians and find some London gigs.

Kefford and Burton soon set about creating The Move. They successfully approached Carl Wayne (born Colin Tooley) but failed to recruit future Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham, who preferred playing with fellow Cedar scenester Robert Plant.

They settled on Vikings drummer Bev Bevan, who had only recently stopped working at the Beehive department store with his school friend Robert Davis, better known as Jasper Carrott. The final piece in the jigsaw was Roy Wood, who was in the Nightriders but had briefly played with Burton in The Mayfair Set.

Their first unofficial gig was at the Belfry in Stourbridge in January 1966, but their real debut was later the same night at the Cedar. Shortly afterwards, they were approached by Secunda, who had made The Moody Blues a success. He kitted them out in ‘gangster’ suits, arranged London gigs and encouraged Wood’s songwriting. Bevan would later recall of Secunda: “he had such incredible self-confidence. We were swept off our feet when we signed the management contract. We were green lads from Birmingham, and he took us shopping in Carnaby Street and immediately changed our image.”

The Move’s early success was driven by their musical prowess, notably Bevan’s explosive drumming and Kefford’s bass, but over time it was Wood’s unexpected songwriting brilliance that would come to the fore. Within months of forming, their debut single, “Night of Fear”, reached number two in the UK chart. The stage gear, meanwhile, shifted from suits to Carnaby Street as they embraced psychedelia. This was evident in their next hit, “I Can Hear the Grass Grow”.

Seeing The Move live in those years was a remarkable, chaotic experience. They devised an anarchic stage act that saw Wayne attack TV sets with axes and set fire to effigies of Adolf Hitler and Harold Wilson. According to Jim McCarthy’s biography of the band, Flowers in the Rain, Joe Boyd, one of the most important promoter-producers of swinging London, regularly attended their weekly Thursday night residency at The Marquee.

“When American musician friends would be in town, I’d say, ‘You gotta hear this band’ and we would go down and listen…A bunch of working-class kids from the Midlands, some taking acid and exploring new possibilities within the format of music. My feeling when I was standing there, watching them, was ‘Holy Shit! This is unbelievable, this would be a mind blower at the Fillimore.”

Boyd tried to get them signed to Electra records, home of The Doors, taking an executive up to the Tower Ballroom in Edgbaston for one of their gigs. He was deeply impressed, but the band weren't taken with the label. Meanwhile, Secunda was fixated on promoting them for domestic chart success.

‘Disgusting, Depraved, Despicable’

He set about organising audacious promotions, including signing their contracts on a nude female model and towing a fake nuclear bomb around Manchester. But it was his decision in the summer of 1967 to to promote the next single “Flowers in the Rain” — as with earlier ones — with controversial postcards delivered to a select audience that proved incendiary. These postcards focused on the relationship between the increasingly disliked Harold Wilson and his political secretary Marcia Williams.

Headed ‘Disgusting, Depraved, Despicable’, they featured a cartoon of a naked Wilson lying in bed next to a woman in a see-through nightie and a Versailles-style wig and mask. She holds a fan emblazoned with “Miss Williams, Harold’s Very Personal Secretary”. Wilson’s wife peeps through the curtains. As well as posting 500 to media and fans, Secunda put a copy through the Number 10 letterbox. Wilson immediately and successfully sued for libel.

This all came at a time of increasing moral panic over the ‘counterculture’; two months earlier The Rolling Stones had been briefly jailed following a raid on Keith Richards’ home. The press — apart from Private Eye — united in condemnation of the postcard.

Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

The Move were lucky to get away without criminal charges, but most of the members had not even seen it before distribution, let alone agreed to it. Secunda was sacked and the planned next single, a song about a mental hospital, “Cherry Blossom Clinic”, backed by a track criticising politicians, “Vote for Me”, was pulled.

This did not stop the band going on a legendary UK tour late that year as the main support for the Jimi Hendrix Experience, above Pink Floyd on the bill. Nor, despite losing the original master tapes, did it stop the long-delayed release of their debut album in March 1968, complete with cover by cooler-than-thou Dutch design collective The Fool.

It had been recorded by early 1967, but Secunda had wanted to build publicity, continually putting back the launch. In the fast-changing musical climate of the late 60s, this delay meant it felt like it belonged to the era of The Beatles’ Revolver, not the new world of experimental concept albums.

As many of the songs had already been released as singles, The Move were sometimes dismissed, despite all the evidence of their musical ability and versatility, as an unimportant pop act from the provinces.

During 1968, tensions grew and grew. Shortly before the album release, Kefford — no longer speaking to the others — quit, feeling slidelined in the band he had been the face of owing to his blond good looks. He was also, quietly, suffering from a nervous breakdown caused by LSD consumption during the Hendrix tour.

Wayne, the oldest in the group and the most established singer, had always seen himself as the real frontman. This led to strains with Wood who gradually took over more vocal duties. Burton saw himself as a serious rock musician. He had become good friends with Jimi Hendrix during the tour — he and Kefford had permed their hair in homage — while together with Wood he sang backing vocals on the track “You Got Me Floatin’” on the superstar guitarist’s second album “Axis Bold As Love”.

Afterwards, he shared a flat with Hendrix’s bassist Noel Redding and was a regular at the Berkshire cottage where Steve Winwood and Traffic would jam for hours in a lysergic haze.

This was at odds with the elaborate string arrangements on the singles, as well as Wood’s whimsical lyrics, based not on drugs but on a book of fairy stories he created while at Moseley School of Art.

One heavier Move single, “Wild Tiger Woman”, was a tribute to Hendrix, but it was their only flop. The reaction was the much more pop chart-topper “Blackberry Way”. Rather than guitars, it used the Birmingham-invented Mellotron, the world’s first synthesiser, already used on “Strawberry Fields Forever”.

Burton had already declared that he hated playing “this shit” during a gig in Stockholm in 1969. He hurled his bass at Bevan, who threw his cymbals back, shouting “when are you leaving then?”. Burton declared that he already had and stormed off stage, kicking over the amplifier stack as he went. The two then had a full-on brawl while Roy Wood carried on playing, solo.

Hi, Kate here. If, like me, you are a bit of a history nerd then you will likely love Jon Neale's back catalogue of stories for The Dispatch. He's a bit like Dan Snow, but without the branding to appeal to middle aged women with a penchant for Oxbridge graduates and tousled hair. And he's entirely focused on the West Midlands.

Anyway, if you like this story, you might want to consider signing up to The Dispatch as a subscriber. You won't find this kind of writing anywhere else in the city - and with our introductory offer, you'll get the first three months for just £1 a week.

The subsequent US tour might have changed his mind. Unknown there, and unencumbered with any pop image, they played to countercultural crowds, headlining at San Francisco’s Filimore West and opening for Iggy Pop’s The Stooges elsewhere.

On their return, they found that their manager, Sharon Osbourne’s dad Don Arden, had sold the band to someone else without their consent. The buyer, Pete Walsh, booked the band onto the cheesy cabaret circuit. Most of the band hated it, but Wayne was in his element.

He left shortly afterwards, to be replaced in early 1970 by Wood’s old friend Jeff Lynne who had already made two classic — if unsuccessful — albums of psychedelic pop with the Idle Race, the latter-day incarnation of the Nightriders.

This coincided with the release of The Move’s second album, Shazam, reflecting Wood’s new progressive direction — extended jams and chamber music interludes. He wanted to bring orchestral instruments into the band — to create an Electric Light Orchestra.

Lynne had turned down Wood’s offers before, but this was a project he could sign up for. The band had, contractually, to remain as The Move for two more albums, but in some ways they were already now a very different band with a very different lineup. The change was made formal in 1972, when they became ELO.

Typically Brummie

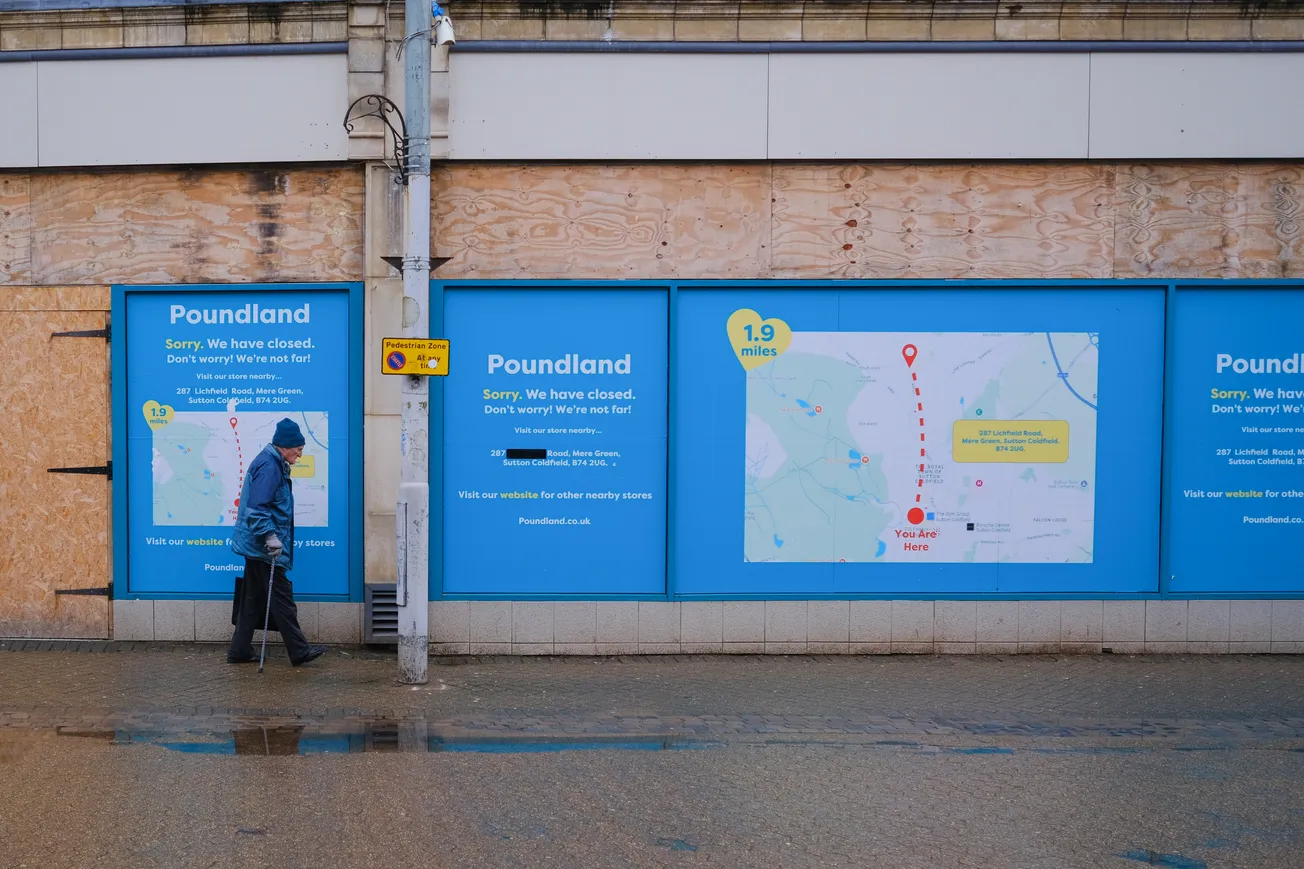

The story of the Move is a familiar one from the period – managers abusing their power over naive young musicians. But in retrospect, they were doomed to be short lived. Five talented members pulled in different directions. The Harold Wilson court case just widened the cracks.

But during that 1966-1968 period, The Move were a unique thing; a bunch of kids from Yardley and Kitt’s Green, Winson Green and Aston, viewed as cool, credible and exciting, all at the peak of the Swinging Sixties.

It’s regularly argued in the music press that The Move are one of the most underrated bands of all time. Hendrix thought they were the best live act in Britain — something reflected in the Marquee recordings and BBC sessions.

Their debut deserves to sit alongside Young Soul Rebels, Handsworth Revolution or Paranoid as one of the greatest records to ever come out of this city. But it’s not just the missteps that dumped them in the Brummie memory hole. Their transition to ELO means The Move are often treated as a prelude to a more successful and long-lived act that, whatever its merits, was often deeply unfashionable. And Roy Wood’s talents as multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and producer are overshadowed by “I Wish it Could be Christmas Every Day” and collaborations with the Wombles.

But their influence is there, in progressive and glam rock, punk and indie. Their occasional vaguely metal sound is intriguing — surely the members of Sabbath saw them in their pomp. The Sex Pistols’ Glen Matlock cited the single "Fire Brigade" as the inspiration for God Save the Queen.

Today, it is Oasis who perhaps bear their stamp most obviously. I can’t find the original magazines, but in the Definitely Maybe era I read interviews in which Noel Gallagher talked about his love for Wood’s songwriting, citing the combination of gnarly guitars and Beatles-esque tunes as a template. Given that Slade and ELO are other influences, there’s a strong Midlands bent to this allegedly most northern of bands.

This whole story of The Move’s underachievement and self-sabotage all feels very typically Brummie. During their 60th anniversary year, perhaps it’s time to rediscover and celebrate them, no matter how short and chaotic their halcyon days were.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

Comments