Welcome to The Dispatch. We’re Birmingham's new newspaper, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Dispatch every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

On a drab Monday morning, I cross Chester Road and pass the ornate sign welcoming me to The Royal Town of Sutton Coldfield, the town I grew up in and, despite leaving in 2008, still think obscurely of as “home.” I’ve done this journey countless times — I was here yesterday, taking my daughter to the park. Today, though, I’m focused on the town.

My grandparents came this way in 1956, moving to Sutton from Erdington. In doing so, they were leaving Birmingham for what was then an independent borough in Warwickshire. Just as their parents had swapped squalid inner-city slums and dying agricultural villages for interwar suburbia, now they too were improving their lot.

Seventy years later, much has changed. Sutton, swallowed by Birmingham in 1974, is in a protracted identity crisis. Since I moved away, it has lost its retail clout, main library, much of its night-time economy, two newspapers, law courts and a fair bit of surrounding countryside — most notably to an enormous Amazon warehouse. Thousands more homes, almost 80% of those earmarked for Birmingham’s greenbelt, are planned.

Yet it’s arguably more exclusive and expensive than ever. It regained its own council and mayor in 2016; ex-council houses on Falcon Lodge estate, parts of which rank among Birmingham’s most deprived areas, cost upward of £250,000. The social mobility my grandparents achieved, with a young family, on Grandad’s wage from the Dunlop factory is, like the tired town centre, a relic of the last century.

A fellow Sutton expat I knew through the various Wolverhampton pubs I worked in once told me, “It’s a strange feeling, knowing you’ll never afford to live in your hometown.” I’ve since learnt exactly what he meant.

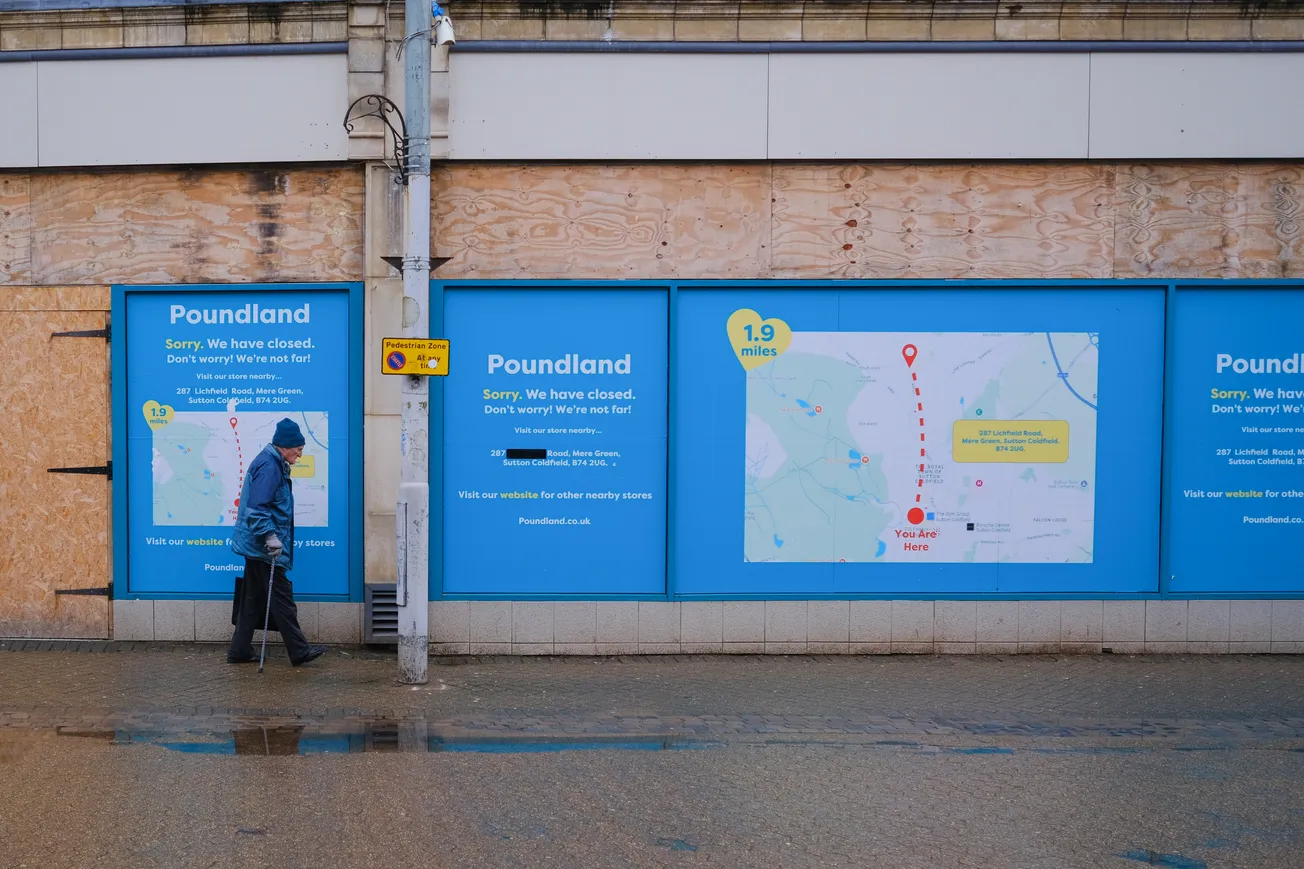

Parking up, I wander down The Parade and around the 1970s-built Gracechurch Centre. There’s a buzz in the air — literally. It’s coming from a faulty alarm on the former Poundland, boarded up since 2024. Combined with the drizzle and faint mist, it lends a dystopian vibe to the ghost-town-like surroundings.

“Wants a bomb dropping on it” was a common sentiment about the area in The Duke, the nearby pub where I spent my late teens and early twenties pouring pints and firming up my handshake. Twenty years on, you’d be forgiven for thinking it had landed. The list of big names that have left or are leaving would wreak havoc on my word-count, but the biggest blow was when Marks & Spencers, the traditional-aspirational brand that encapsulated what Sutton stood for, abandoned their once-grand store in 2019. The site has sat empty ever since. One trader describes it as having “ripped the soul” from the town centre.

Ironically, it marks Sutton out as nothing special. Suburban centres like this, built before the advent of retail parks, decimated by online shopping and COVID, simply aren’t needed anymore. Car-owning locals do their physical shopping at Tamworth’s Ventura Park, eight miles away, where the parking’s free. The permanent closure of Sutton Library in the good-as-derelict Red Rose Centre is similar: tragic for those of us who treasured it, but that’s 2020s Britain.

Flattening everything and starting again feels inevitable — it’s been on the cards for years. But what should replace it, who should it be for, and why isn’t it happening?

Seeking answers, I call James, an architectural designer and old schoolmate. It’s been years — we both had hair and no kids last time we met — but he invites me to his office nearby.

“It’s managed decline,” he says, a term I’m more used to hearing in connection with 1980s mining communities than Sutton Coldfield. “I looked at renting a unit to use as a sports bar, but they were unfeasibly short leases. They offered three years, so that tells you they’re not really looking for tenants.”

The plan, he explains, is for Sutton to become a “living centre,” breaking the one-way “concrete collar” ring road, opening up the river that trickles under the town centre and replacing life-expired, large-floorspace units with buildings more suited to modern business. Sticking expensive retirement apartments on top simply makes business sense, however loud the tuts.

“Baby boomers have got lots of money,” he states. “They’ll pay £400,000 for a decent-sized, two-bedroom apartment. Twenty-year-olds looking to leave home don’t have £400,000, so you can see why they’re doing it.” But, he adds, the knock-on effect might be to free up family housing. “A lot of houses in Sutton are underutilised: people are living out their retirement in four, five-bed houses.”

James puts me in touch with a well-connected local who’s privy to redevelopment plans but has to stay anonymous. Over the phone, he outlines why the decline continues: the Gracechurch Centre is joint-owned by Birmingham Property Group and London-based developers SAV Group. Birmingham city council own most of the opposite side of the Parade and the Red Rose Centre, where Sainsbury’s still hold a lease on the empty store they left 25 years ago. With high building costs, leasing issues and, my man reckons, no “cohesive masterplan” for the area, wholesale redevelopment is “pointless.” It’s cheaper for owners to sit on their assets.

One initiative launched to nurse Sutton through this interregnum is the Business Improvement District (BID), which encourages visitors by organising markets and entertainment. I know from experience that they’re successful, but there are dissenting voices.

Jack is another local I’ve known since childhood — he and my brother used to skateboard together. Still wearing the skater uniform of baggy jeans, hoodie, and beanie, Jack has been landlord of Sutton’s oldest pub, the Three Tuns, since 2018. Hunched over a pint, he explains his issue with the BID: “It’s a tax, based on your rateable value, so I’m forced to pay them four figures a year. My argument is that we get no benefit, because everything happens down on The Parade.”

The BID used to help with the cost of staging the annual Tuns Fest, which raises money for local charities. Post-pandemic, however, Jack claims, “They decided the BID wasn’t responsible for supporting independent businesses, even though I fund the BID. They pulled the rug from under me.” (the BID were contacted for comment).

He’s also witnessed the passing of Sutton’s nightlife: “The biggest change is that the seven or eight bars and clubs on the Parade have all gone. Walk down there at 11 o’clock on a Friday or Saturday night, there’s no one there. Kids today don’t drink. They want a vape and a McDonald’s and that’s all they’re interested in.”

Jack admits he doesn’t have the solution. All he sees is a town trading on its postcode, costing more, offering less.

If you enjoying this story by Shaun and you want to get access to our fantastic subscriber-only stories, why not join up as a Dispatch member today?

You'll be able to read our exclusive analysis on how, and why, Manchester is outstripping Birmingham in the battle of the second cities, or this historical deep-dive into how the city's slum clearances forever changed its fortunes.

You will also get access to our entire back catalogue of amazing stories and, better yet, you will be supporting our mission to give this city proper local journalism. Plus, a subscription is just £2 a week. Sign up now to back the local reporting Birmingham deserves.

Yet there are flickers of hope. Everyone I talk to mentions Silver Tree Bakery, which recently (bravely?) opened in the Gracechurch. It’s a success story people are genuinely invested in. They also highlight nearby Boldmere where, similar to Stirchley, a once down-at-heel row of shops is now a thriving mini-centre, blending independent businesses with busy big-name coffee shops.

Similar is true of Wylde Green and Mere Green. Much as they mourn the big M&S, those who can afford to live here can, and do, love supporting local entrepreneurs and, post-pandemic, the chance for in-person connection.

Arguably, though, such changes also click with the Suttonian psyche because they hark back to “how it used to be,” real or imagined. That same mindset, which has never accepted annexation by Birmingham and campaigned to reaffirm Sutton’s ‘Royal’ status in 2014, prompted the vote to reinstate the town council. The results, though, appear largely performative. It added a levy to residents’ council tax, yet almost everyone I ask about it shrugs. One interviewee, a lifelong resident, didn’t even know the council was back.

Other changes, the kind that bring progress marching over Sutton’s semi-autonomous borders evoke stronger emotions, from hair-trigger rants to resignation. In the Gracechurch, I chat to Zena, a friendly fifty-something with a brown bob and red fleece. She’s lived in Sutton since childhood but says if plans to build 300 homes on Newhall Country Park, five minutes from her doorstep, go ahead, she’s off. “It’s the only reason I’ve stayed,” she sighs.

I sympathise, but I also think of a photo of my mom in my grandparents’ back garden, taken in the early ‘70s. Behind her are some distant fields. By the late ‘90s, they were the housing estate I walked through on my way to school — the one Zena lives on.

I’m not sneering; I get it. It’s hard not take change personally. It can be sad watching your hometown, the world of your youth, become unrecognisable. It’s not what it was; but whatever comes next won’t be the same.

Back in the Tuns, I meet Zoe, who I know through the many local causes she’s been involved with over the last decade. Our conversation focuses on politics, so it’s fitting that we sit opposite the office of the town’s long-serving Tory MP, Sir Andrew Mitchell. (Sutton has never not been Conservative).

Well-spoken, bespectacled, and smartly dressed with silver-blonde hair, Zoe arrived in Sutton 20 years ago from North London to a rude awakening. “I thought I was coming to Birmingham, a multicultural city,” she confesses. “It shocked me to go days without seeing anybody who wasn't white.” (I can testify to this: there were perhaps half-a-dozen non-white students in my secondary school year-group). “Nowadays, we're definitely not a multicultural town, but there is more of a mix.”

Zoe’s community involvement makes her well-placed to observe the town’s political machinations. Ironically, given her left-of-centre views (rare round here), she’s the only person I speak to with a positive word for the town council, pointing out that their funding extended Sutton Library’s life by several years.

But the goodwill ends there. “I do think [Sutton]’s become more right-wing,” she says, raising the impact of Reform and appearance of flags — and Tory appeasement thereof. “A flag went up near the council leader’s house. As I understand, he had a quiet word and it was taken down. He didn’t want it there, but [the council] weren’t going to take them down anywhere else.” The council confirm they’ve not removed any flags, but deny one was ever outside their leader’s home.

Zoe discusses weekly protests outside the former Ramada hotel in Wylde Green, currently a hostel for asylum seekers. She also mentions James Sullivan, Trustee of the local St. Chad’s Sanctuary charity, recently awarded a BEM for his work with refugees. “I wrote to Andrew Mitchell and the council saying, ‘I hope you can celebrate him’... None of them have been in touch. I think there's a bit of a fear — and a lack of leadership.” We gaze out the window, and I think how apt the flaking blue paint on the MP’s window-frames is.

The council and Andrew Mitchell’s office say they’ve no record of any correspondence but highlight the MP’s praise of Sullivan in a recent newsletter. “I wonder if he knows St. Chad’s works with residents in the old Ramada,” Zoe retorts — Mitchell is campaigning for the hostel’s closure.

As I leave, I reflect that I didn’t find any clear answers about Sutton’s future identity. The shadow of the bomb the Duke regulars wanted all those years ago looms over its centre, but it’s unclear when it will fall. The plans for thousands more homes, stretching Sutton’s suburban sprawl and infrastructure further, concreting more green space, add yet more uncertainty about how it will look in 10 years’ time.

Elected officials find themselves boxing other shadows, too: those from flags fluttering on Sutton’s most working-class streets. Personally, I don’t think Brum’s deepest blue constituency will turn turquoise, but then I never would’ve predicted that the busy library I visited most days and crowded venues I got drunk in most weekends would vanish, or that I too couldn’t afford to live in my hometown.

I head up Birmingham Road, back the way my grandparents came.

If someone forwarded you this newsletter, click here to sign up to get quality local journalism in your inbox.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Dispatch and reach over 25,000 readers, you can contact us or visit our advertising page below for more information

Comments